Exploring Life through the Written Word

"Odysseus woke from sleep on native ground at last—he'd been away for twenty years—but failed to know the land for Athena, daughter of Zeus, had wrapped him round in mist to make him unrecognizable while she told him all he needed to know."

Dear friends,

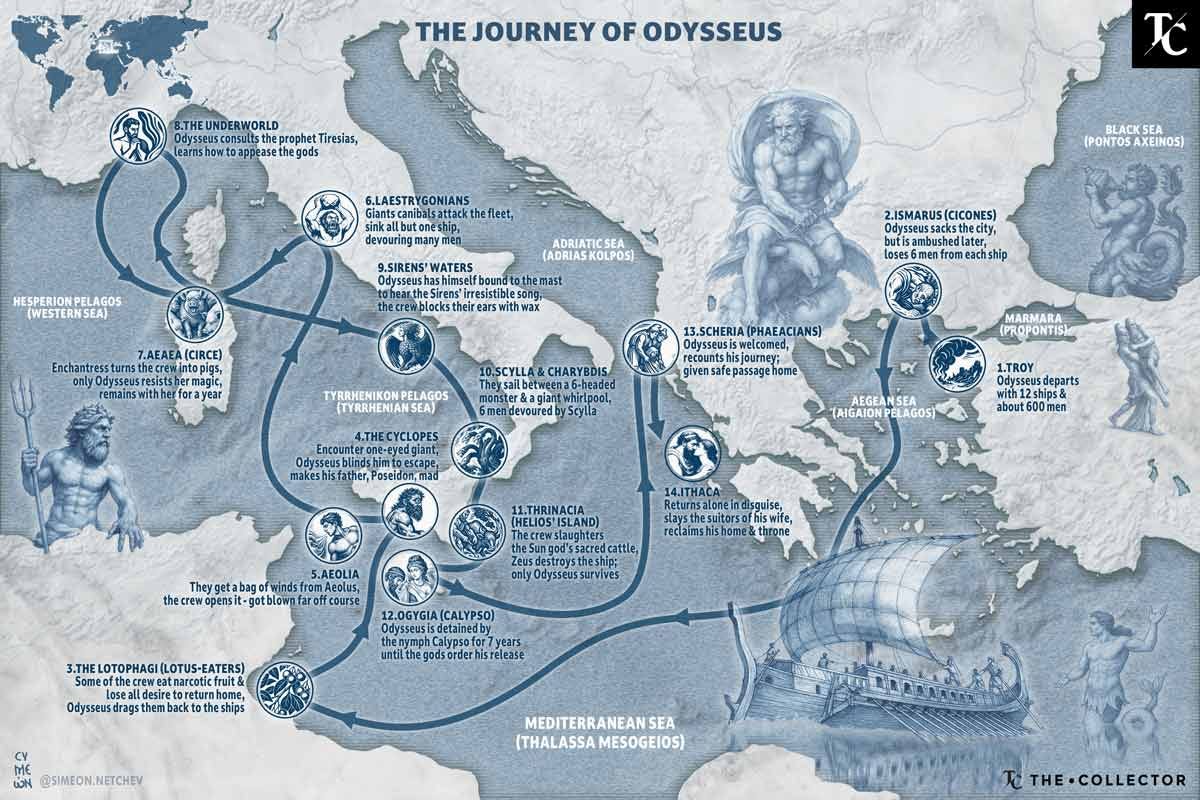

Book 13 of Homer's The Odyssey marks one of the most significant structural pivots in the entire epic, as the narrative shifts from supernatural adventure to domestic intrigue, from wandering hero to homecoming king. This book represents the culmination of Odysseus's physical journey while simultaneously beginning his most complex challenge: reclaiming his identity and his kingdom from the forces that have usurped his place during his long absence. The chapter operates as both resolution and commencement, ending the wanderings while initiating the final confrontation that will determine whether Odysseus can truly come home.

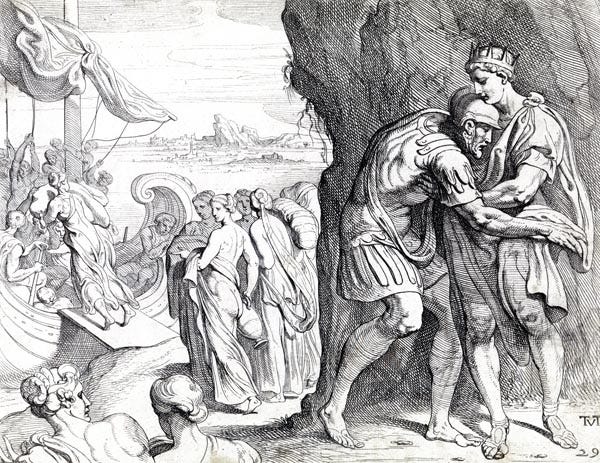

The book opens in the palace of Alcinous, king of the Phaeacians, where Odysseus has just finished recounting his adventures to the assembled court. The impact of his narrative on his hosts has been profound—the Phaeacians sit in stunned silence, moved by the tragic scope of his experiences and awed by his survival of trials that have destroyed so many others. King Alcinous breaks the silence by acknowledging the power of Odysseus's story and reaffirming his promise to provide safe passage home, declaring that such a hero deserves the finest assistance they can provide.

The Phaeacian response to Odysseus's tale reveals their understanding of the sacred obligations of hospitality and their recognition of his extraordinary worthiness as a guest. Alcinous calls upon his nobles to contribute additional gifts beyond those already promised, arguing that Odysseus's sufferings and heroic stature merit exceptional generosity. The king himself provides a magnificent chest to hold these treasures, while Queen Arete personally adds fine clothing and gold. This spontaneous outpouring of gifts transforms Odysseus from a suppliant stranger into an honored friend, demonstrating how proper guest-friendship should operate when host and guest fulfill their respective roles perfectly.

The preparations for departure take on a ritual quality that emphasizes the significance of this transition. Arete supervises the packing of Odysseus's gifts in the bronze-bound chest and secures it with an intricate knot that she herself has devised, ensuring that his treasures will remain safe during the voyage. The queen's personal attention to these details reflects both practical wisdom and symbolic recognition that Odysseus is carrying more than material wealth—he bears the tangible proof of Phaeacian hospitality and the means to reestablish his status as a king worthy of respect.

As evening approaches, the Phaeacians prepare for the final feast that will conclude their hospitality. Odysseus participates in the ritual bath that cleanses him for the journey ahead, but his attention remains focused on the approaching moment of departure. When Arete appears in her beautiful robes, he takes formal leave of her, acknowledging her crucial role in securing his passage home and expressing gratitude for her wise counsel. This farewell scene emphasizes the queen's importance as both hostess and advisor, reflecting the significant role that aristocratic women played in ancient diplomatic relationships.

The final banquet proceeds with appropriate ceremony, but Odysseus remains watchful of the sun's progress across the sky, eager for nightfall when the Phaeacian ship will carry him home. His impatience reflects not mere desire to complete his journey but awareness that every moment of delay increases the danger to his family and kingdom. When he finally addresses the assembled court, his words acknowledge both their extraordinary hospitality and his urgent need to depart, creating a graceful balance between gratitude and necessity.

As darkness falls, the Phaeacians escort Odysseus to their swiftest ship, where they have prepared a comfortable bed for him on the stern deck. The crew, renowned throughout the ancient world for their seamanship, takes up their oars and begins the miraculous voyage that will carry him across the sea to Ithaca in a single night. As the ship cuts through the dark waters with supernatural speed, Odysseus falls into a deep, peaceful sleep—the first truly restful slumber he has enjoyed since leaving Troy.

The description of this sleep emphasizes its restorative quality and symbolic significance. Homer compares it to death in its depth and stillness, but unlike the death-like unconsciousness that Circe imposed when the gods prevented him from stopping his men's sacrifice of the sacred cattle, this sleep represents peace and approaching fulfillment. The image suggests a kind of rebirth—the wandering hero dies in his sleep aboard the Phaeacian ship, and the returning king will awaken on Ithaca's shores.

The Phaeacian ship arrives at Ithaca just before dawn, its crew guided by their intimate knowledge of the island's coastline to a secluded harbor where Odysseus can land unobserved. The sailors gently lift the sleeping hero and carry him to shore without waking him, placing him on the sand beneath an olive tree. They then carefully arrange his treasure chests nearby before departing silently, their mission of divine assistance complete. This careful attention to his comfort and security demonstrates the Phaeacians' understanding that their obligation extends beyond mere transportation to ensuring his safe and dignified arrival.

When Odysseus awakens, he finds himself in a landscape that seems both familiar and strange. The long years of absence have altered his perception, and the early morning mist obscures familiar landmarks, creating an atmosphere of uncertainty and disorientation. His first response is not joy at homecoming but suspicion that the Phaeacians have deceived him and deposited him on some unknown shore. This reaction reflects the psychological impact of his long exile—the wandering hero has become so accustomed to deception and hostile strangers that he cannot immediately trust even in the reality of his return.

Odysseus's initial survey of his surroundings reveals both the physical treasures that the Phaeacians have given him and his own changed perspective on his homeland. He counts his gifts carefully, finding everything intact, but he walks the shoreline "groaning, sick at heart," unable to recognize the place that should be most familiar to him in the world. This alienation from his own homeland reflects one of the deepest psychological challenges of homecoming—the returning exile must rediscover a place that has continued to exist and change during his absence.

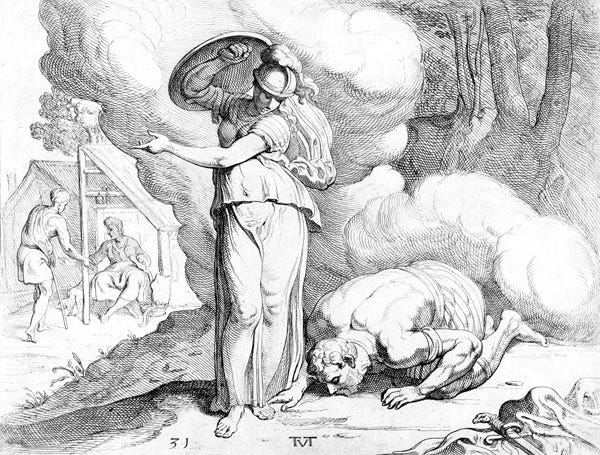

The intervention of Athena marks the beginning of Odysseus's reintegration into his homeland and his assumption of the identity that will allow him to reclaim his kingdom. The goddess appears to him in the form of a young shepherd, and Odysseus, still maintaining the cautious habits developed during his wanderings, greets this apparent stranger with a fabricated story about his identity and origins. He claims to be a Cretan fugitive who has killed a man and fled his homeland with stolen treasure, demonstrating how thoroughly his years of exile have trained him in protective deception.

Athena's response reveals both amusement and approval at Odysseus's continued cunning. She praises his skill at deception while simultaneously revealing her own identity and confirming that he has indeed reached Ithaca. The goddess explains that she has been protecting him throughout his journey, though often from a distance due to her reluctance to openly oppose her uncle Poseidon. Her presence now signals that the time for concealment is ending and that she will provide active assistance in the challenges ahead.

The revelation of Athena's identity and her confirmation that he has truly reached home triggers a profound emotional response in Odysseus. He kisses the ground of Ithaca and prays to the nymphs of the island, acknowledging both his gratitude for survival and his recognition that he has returned to the place where he belongs. This gesture transforms the alien landscape into sacred ground, reestablishing the spiritual connection between hero and homeland that exile had severed.

Athena then provides crucial intelligence about the situation Odysseus will face in reclaiming his kingdom. She confirms that Penelope remains faithful despite twenty years of pressure from the suitors, that his son Telemachus has grown to worthy manhood and is even now seeking news of his father, and that his father Laertes lives in grief-stricken isolation on his farm. However, she also warns that over a hundred suitors have occupied his palace, consuming his wealth and pressuring his wife to remarry, creating a situation that requires careful strategy rather than direct confrontation.

The goddess's counsel emphasizes the need for disguise and strategic patience. She explains that Odysseus cannot simply announce his return and expect to reclaim his throne—the suitors are too numerous and too well-entrenched to be overcome through open challenge. Instead, he must gather intelligence, test loyalties, and prepare the ground for a coordinated strike that will eliminate his enemies while protecting his family. This advice transforms the hero from wanderer to strategist, requiring him to apply his cunning to domestic rather than supernatural challenges.

To facilitate this covert approach, Athena transforms Odysseus's appearance, aging his face, withering his limbs, and covering his head with sparse gray hair. She dresses him in tattered clothes and gives him a beggar's sack and walking stick, creating a disguise so complete that even those who know him best will not recognize him. This transformation represents more than mere camouflage—it symbolizes the death of the wandering hero and the birth of a different kind of challenger, one who will work from within the system to reclaim what is rightfully his.

The goddess also conceals his treasure in a sacred cave dedicated to the nymphs, ensuring that his wealth will remain safe while he undertakes the dangerous work of reconnaissance and preparation. She instructs him to seek out Eumaeus, his loyal swineherd, who has remained faithful during his absence and can provide both shelter and information about the current state of affairs in the kingdom. This plan demonstrates Athena's understanding that successful homecoming requires not just arrival but careful preparation for the challenges that await.

The book concludes with Athena's departure for Sparta, where she will retrieve Telemachus from his own journey and guide him safely back to Ithaca. Her promise to coordinate the return of both father and son sets up the reunion that will provide crucial support for the final confrontation with the suitors. The goddess's active involvement in arranging these meetings demonstrates that the restoration of Odysseus's kingdom represents divine will as well as human effort, requiring both mortal cunning and immortal assistance to achieve success.

Meanwhile, the narrative returns briefly to the Phaeacians, whose generous assistance to Odysseus triggers divine punishment from Poseidon. The sea god, enraged by their interference with his persecution of Odysseus, turns their returning ship to stone just as it enters their harbor, fulfilling an ancient prophecy that their kindness to strangers would eventually bring divine wrath upon them. This episode demonstrates the cost of opposing divine will, even when that opposition takes the form of heroic generosity and proper hospitality.

Literary Analysis

Book 13 of The Odyssey marks the most significant structural transformation in The Odyssey, as Homer shifts the narrative focus from fantastic adventure to realistic domestic intrigue. This transition reflects the epic's deeper concern with the relationship between heroic achievement and social reintegration, exploring how extraordinary experiences in distant lands translate into practical challenges at home. The movement from supernatural trials to political maneuvering demonstrates the epic's sophisticated understanding that true heroism must ultimately prove itself in ordinary human contexts rather than exotic circumstances.

The Phaeacian episode that opens the book provides a model of ideal guest-friendship that serves as both climax and contrast to the hospitality themes that have run throughout Odysseus's wanderings. The spontaneous generosity of Alcinous and his nobles, triggered by their appreciation for Odysseus's story, demonstrates how proper xenia should operate when both host and guest fulfill their roles completely. The king's call for additional gifts beyond those already promised reflects the ancient principle that extraordinary guests deserve extraordinary treatment, while the careful attention to practical details like Arete's special knot demonstrates how hospitality extends beyond ceremonial gestures to ensure real protection and assistance.

The contrast between this ideal hospitality and the perverted guest-friendship that Odysseus will encounter in his own palace creates dramatic irony that drives the remaining narrative. The Phaeacians' generous treatment of a stranger highlights the suitors' violation of hospitality norms in consuming their host's wealth while threatening his family. This juxtaposition establishes the moral framework for understanding the final confrontation—the suitors have violated the same sacred obligations that the Phaeacians honor, making their destruction not merely politically necessary but morally justified.

Odysseus's sleep during the voyage home functions as a symbolic death and rebirth that marks his transition from wandering hero to returning king. Homer's comparison of this sleep to death emphasizes its transformative nature—the exhausted exile who boards the Phaeacian ship represents the end of one phase of heroic experience, while the figure who will awaken on Ithaca's shores must become a different kind of hero entirely. The peaceful quality of this sleep, contrasting sharply with the troubled rest that has characterized much of his journey, suggests that this transformation represents healing and restoration rather than loss or diminishment.

The initial disorientation that Odysseus experiences upon awakening reflects the psychological complexity of homecoming after extended exile. His inability to recognize his own homeland speaks to fundamental questions about identity and belonging—the place that should be most familiar becomes alien when approached from the perspective of long absence and traumatic experience. Homer's insight that exile changes not only the traveler but also his relationship to home anticipates modern understanding of how displacement affects psychological and cultural identity.

The careful description of Odysseus's suspicious reaction to his homecoming demonstrates the psychological realism that distinguishes Homer's treatment of heroic themes. Rather than presenting homecoming as an immediate return to previous identity and relationships, the epic acknowledges that extended trauma and displacement create lasting changes in perception and response patterns. Odysseus's assumption that he has been deceived reflects the defensive adaptations that have enabled his survival but now threaten to prevent his successful reintegration into his own society.

Athena's Role as Divine Coordinator and Strategic Advisor

Athena's intervention in Book 13 transforms her from distant protector to active collaborator, marking a crucial shift in the relationship between divine assistance and human agency. Her appearance in disguise as a young shepherd reflects the goddess's understanding that successful divine intervention often works through seemingly natural encounters rather than overwhelming supernatural displays. This approach allows Odysseus to maintain agency and dignity while receiving the guidance necessary for success in the challenges ahead.

The goddess's praise for Odysseus's continued deception reveals Homer's sophisticated understanding of how divine and human cunning complement each other. Athena's appreciation for the false story that Odysseus tells demonstrates that the gods value skillful thinking and strategic adaptation rather than naive honesty or reckless bravery. Her response suggests that divine approval goes to those who use their intelligence effectively rather than those who simply follow conventional heroic models.

The intelligence briefing that Athena provides about conditions in Ithaca demonstrates how divine assistance can take practical, strategic forms rather than magical solutions. Her detailed information about Penelope's situation, Telemachus's journey, and the suitors' behavior provides exactly the knowledge that Odysseus needs to develop effective tactics. This form of divine help empowers human planning and decision-making rather than replacing it, creating a collaborative model where gods and mortals work together as allies rather than in a relationship of dependence.

The physical transformation that Athena imposes on Odysseus represents one of the most psychologically complex uses of divine power in the epic. The disguise she creates is not merely cosmetic but represents a fundamental alteration of identity that allows him to move unrecognized through his own kingdom. This transformation reflects the principle that successful reconnaissance requires the observer to become invisible within the social environment being studied, a concept that applies to both military intelligence and social understanding.

The coordination between Athena's assistance to Odysseus and her simultaneous mission to retrieve Telemachus demonstrates divine planning that operates on multiple levels simultaneously. The goddess's ability to orchestrate the return of both father and son reflects strategic thinking that considers how individual actions contribute to larger patterns of success. This coordination anticipates the reunion scene that will provide crucial emotional and practical support for the final confrontation with the suitors.

The Psychology of Homecoming and Identity Reconstruction

Book 13's exploration of the psychological challenges of homecoming provides insights into universal experiences of displacement, return, and identity reconstruction that transcend its specific ancient context. Odysseus's difficulty in recognizing his homeland reflects the broader challenge of reintegrating into familiar environments after extended absence and traumatic experience. The text demonstrates how exile changes not only individuals but also their relationships to places and communities that previously defined their identity.

The process of psychological reorientation that Odysseus undergoes—from suspicion and disorientation to recognition and emotional connection—provides a framework for understanding how displaced individuals must reconstruct their relationships to home and identity. His initial assumption that he has been deceived reflects defensive patterns developed during extended trauma, while his eventual acceptance of homecoming requires overcoming these protective mechanisms that may no longer serve his best interests.

The ritual elements of Odysseus's reintegration—kissing the ground, praying to the local nymphs, acknowledging the sacred nature of his homeland—demonstrate how successful homecoming requires not just physical return but spiritual and emotional reconnection. These gestures transform the initially alien landscape into sacred space, reestablishing the bonds between person and place that exile had severed. The scene suggests that homecoming is an active process requiring conscious commitment rather than an automatic result of physical presence.

The strategic patience that Athena counsels reflects understanding that successful reintegration often requires gradual approach rather than immediate assertion of previous identity and status. The goddess's advice acknowledges that the returning exile cannot simply resume former roles but must carefully assess changed circumstances and rebuild relationships that may have been damaged or altered during their absence. This guidance applies to contemporary experiences of return from military deployment, immigration, long-term hospitalization, or other forms of displacement.

The disguise that conceals Odysseus's identity while allowing him to observe his homeland reflects the paradox that sometimes understanding familiar environments requires approaching them from unfamiliar perspectives. The beggar's role that he will assume provides access to information and insights that would be unavailable to someone operating from his previous position of authority. This principle applies to contemporary situations where understanding organizational or social dynamics requires stepping outside established roles and hierarchies.

Historical Context and Social Implications

Book 13 reflects several crucial aspects of ancient Greek social organization, particularly regarding the obligations of hospitality, the nature of kingship, and the relationship between individual identity and community membership. The Phaeacian model of ideal guest-friendship provides a standard against which other examples of hospitality in the epic can be measured, while also demonstrating how such relationships created networks of mutual obligation that extended beyond immediate practical benefits.

The concept of divine punishment for excessive generosity, as demonstrated in Poseidon's transformation of the Phaeacian ship, reflects ancient understanding of the complex relationship between divine favor and human action. The episode suggests that even virtuous behavior can trigger divine displeasure when it conflicts with larger divine plans, creating a theological framework where moral behavior must be balanced against cosmic order. This understanding helps explain the tragic dimensions of ancient Greek literature, where good intentions and proper behavior do not guarantee positive outcomes.

The emphasis on treasure and gift-giving throughout the Phaeacian episode reflects the central role that material wealth played in ancient aristocratic identity and political relationships. The careful attention to Odysseus's accumulation of gifts demonstrates how successful guest-friendship created tangible proof of social status and divine favor. These treasures represent more than mere wealth—they provide evidence of his worthiness and the respect he has earned from foreign rulers, credentials that will be crucial in reestablishing his authority in Ithaca.

The strategic approach to reclaiming royal authority that Athena counsels reflects ancient understanding of how political power operated in small-scale societies where personal relationships and individual reputation played crucial roles in maintaining legitimacy. The goddess's advice acknowledges that royal authority cannot be simply asserted but must be demonstrated through actions that prove worthiness and gather support from key constituencies. This approach reflects the reality of ancient kingship, where rulers maintained power through complex negotiations with nobles, dependents, and divine forces.

The coordination between divine assistance and human intelligence that characterizes Athena's help reflects ancient Greek understanding of how gods and mortals should work together to achieve important goals. The goddess's provision of information, strategic advice, and practical assistance demonstrates ideal divine intervention that enhances human capabilities rather than replacing them. This model influenced later philosophical and theological thinking about the relationship between divine providence and human agency.

Contemporary Relevance and Modern Applications

The psychological and social dynamics explored in Book 13 continue to resonate with contemporary experiences of displacement, return, and identity reconstruction. Military personnel returning from deployment, immigrants reconnecting with home countries, and individuals reintegrating into communities after extended absence face challenges similar to those that Odysseus encounters in recognizing and reconnecting with his homeland.

The initial disorientation and suspicion that characterizes Odysseus's awakening on Ithaca reflects contemporary understanding of how extended trauma and displacement can affect perception and response patterns. Modern psychology recognizes that individuals who have survived dangerous or highly stressful situations often develop defensive mechanisms that may persist even after the threat has passed, creating challenges for successful reintegration into peaceful environments.

The strategic approach that Athena counsels—gathering intelligence, testing loyalties, and building support before direct confrontation—provides frameworks applicable to contemporary situations involving organizational change, political reform, or community development. The principle that successful transformation often requires working within existing systems rather than attempting immediate revolutionary change reflects insights from modern management theory, political science, and social change methodology.

The theme of disguised identity that enables Odysseus to observe his homeland from new perspectives speaks to contemporary understanding of how stepping outside established roles and hierarchies can provide valuable insights into organizational and social dynamics. Modern management and social research techniques often employ similar approaches, using participant-observation methods that allow researchers to understand systems from insider perspectives while maintaining analytical distance.

The coordination between multiple actors working toward shared goals—Athena's simultaneous assistance to both Odysseus and Telemachus—reflects contemporary understanding of how complex challenges require systematic approaches that address multiple dimensions simultaneously. Modern project management, organizational development, and social intervention strategies often employ similar coordination techniques to ensure that individual actions contribute to larger patterns of success.

The careful attention to material resources and practical support that characterizes the Phaeacian assistance speaks to contemporary understanding of how successful reintegration requires not just emotional and psychological support but tangible resources that enable practical problem-solving. Modern approaches to supporting returning veterans, refugees, and other displaced populations recognize the importance of combining emotional care with practical assistance in housing, employment, and community connections.

The model of ideal hospitality that the Phaeacians provide offers insights relevant to contemporary discussions about community responsibility toward strangers, refugees, and other displaced individuals. The spontaneous generosity triggered by appreciation for Odysseus's story suggests how personal narrative and human connection can motivate practical assistance and community support.

Perhaps most significantly, Book 13's exploration of how homecoming requires active reconstruction of identity and relationships rather than simple resumption of previous roles speaks to contemporary understanding of how major life transitions require conscious adaptation and community support. The text demonstrates that successful return involves not just individual adjustment but community recognition and acceptance of changed circumstances and evolved identity.

The strategic patience that successful reintegration requires—Athena's counsel to gather information and build support rather than immediately asserting authority—reflects contemporary insights from fields ranging from conflict resolution to organizational change management. The principle that lasting transformation often requires gradual approach and careful preparation rather than dramatic immediate action applies to numerous modern contexts where individuals or groups must navigate complex social and political environments to achieve important goals.

Study Questions

The Psychology of Homecoming: Odysseus initially fails to recognize his own homeland and suspects the Phaeacians have deceived him, despite having reached his ultimate goal. What does this reaction reveal about the psychological effects of long exile and trauma? How does Homer's portrayal of homecoming as a gradual process of recognition and reconnection rather than immediate joy reflect realistic aspects of displacement and return?

Divine Assistance and Human Agency: Athena provides Odysseus with crucial intelligence, strategic advice, and physical disguise, yet insists that he must accomplish his goals through his own cunning and effort. How does this collaboration between goddess and hero reflect the epic's understanding of the relationship between divine help and human responsibility? What does this model suggest about how external support should function in human achievement?

Strategic Deception versus Honest Return: Athena counsels Odysseus to approach his homeland in disguise and gather intelligence rather than announcing his return openly. This strategy requires him to deceive even loyal supporters initially, including his wife and father. How do we evaluate the ethics of this approach? When might strategic deception serve justice better than immediate honesty, and what are the risks of such an approach?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 14. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled The Loyal Swineherd and spans pages 301-318. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled A Loyal Slave and spans pages 332-349.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you've found value in my work and it has helped, informed, or entertained you, I'd be grateful if you'd consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue creating content and means more than you know. Even small contributions make a real difference and allow me to keep sharing my work with you. Thank you for reading and for any support you're able to offer.

Affiliate links: You can click on the title of any book mentioned in this article to purchase your own copy. These are affiliate links, earning me a very small commission for any purchase you make.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Your essay is a thought-provoking look at how Book 13 brings to light the forces at play when we return to a place from our youth or from which we have been otherwise absent for an extended period. In the interim, we have changed in ways that cause us to perceive places and people in a different light. The places and people from long ago change themselves. On top of all of that, our memories of how people and things were are almost always faulty. When the additional aspect of how trauma changes us is added to the mix, it's small wonder that returning soldiers who have been in combat can face major challenges reintegrating with family and friends.

The deception by Odysseus reflects a wariness that often occurs with returning combat veterans or refugees who are escaping trauma in their homelands. We don't have Athena to help them, so it's up to the rest of us to meet them with compassion and understanding.

Resolution and commitment, what a solid footing in this descriptive summary of Book XVIII.

I like the idea of strategy within this book - of disguise and patience, gathering intelligence, and testing loyalties. What it means to gather information to integrate that information into strategy. While in this chapter that might mean an upcoming battlement, in a whole life experience it could be how to find success and to persevere. There's something to be said for not rushing forward, to temper a movement for a greater result. Of course this can be a double edged sword, right? A patient rabble-rouser could find tremendous success.

Odysseus is forced to change his view and perspective. It isn't as easy as just docking the ship. Instead he has to relearn the lay of the land. He has to break his warrior tendencies, embrace more of the current predicament for a longer legacy and proof of his moral personhood.