My Willa

Examining the life and work of Willa Cather

Exploring the Stories of Our Lives

“Artistic growth is, more than anything else, a refining of the sense of truthfulness. The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist, knows how difficult it is.” - Willa Cather

From the myriad stories of westward expansion, cowboy adventures, and frontier life, Willa Cather stands alone among the canonical writers of American Literature for her emphasis on female protagonists. The women in Cather’s family were strong and independent, allowing her to see first-hand how vital they were in the westward expansion. Observing the example of these strong role models, she infused her writing with personal experience, rejecting the conventional trope of weak women in need of men by empowering her female characters while simultaneously establishing herself as an authoritative voice of the American West.

Born in rural Virginia in 1873, she moved to Nebraska at nine with her parents, siblings, and extended family, following in the footsteps of her grandparents, who had moved a few years prior. Their beginnings were modest, sleeping first in wagons or under the stars before graduating to sod dugouts and eventually building a cabin. They passed the first two years of frontier life in this way before moving to the burgeoning town of Red Cloud. Small by Eastern standards, Red Cloud connected farms and villages in the region, providing a nexus of stability for those daring enough to brave the journey West to start a new life. Cather found town life pleasant with its abundance of activity, mainly due to the railroad, which brought supplies, mail, and news from the East. It was an exciting and diverse environment for a young woman surrounded by neighbors from Germany, Scandinavia, Bohemia, and Quebec. All their foods, languages, and cultures added to the excitement of a frontier town. Red Cloud had an indelible impact on Cather and would feature prominently in her writing as the inspiration for numerous small Nebraska towns.

Cather resisted gender norms throughout her life. As a teen, she shaved her head, cross-dressed, and called herself William for some time. While that phase didn’t last, she made the point she would not remain beholden to the cultural ideas of what a woman should be. Her willingness to defy societal expectations was courageous in an era with strict religious and moral constraints.

Cather developed an interest in writing during high school; however, frontier life seldom provided an environment conducive to artistic growth. She discovered an eclectic academic community when she moved to Lincoln to attend the University of Nebraska. A Rhetoric professor, recognizing Cather’s talent, sent one of her essays to the Nebraska State Journal, which accepted it for publishing. Seeing her words in print fueled the desire to write, leading to regular contributions to the Journal, including a weekly column covering local events, literature, arts, theater, and music.

After college, Cather realized Nebraska’s frontier life, even in Lincoln, provided limited opportunities for a woman to pursue a career. In 1893, she moved to Pittsburgh, where she took a job writing articles and poetry for Home Monthly, a periodical similar in style to the well-known Ladies Home Journal. Over time, she took over the editing responsibilities and began to write for other publications, including the Pittsburgh Leader. She became a well-known critic, commenting frequently on Pittsburgh's vibrant social and cultural nightlife. In addition to her writing career, she became a high school English teacher, living and working in Pittsburgh for ten years.

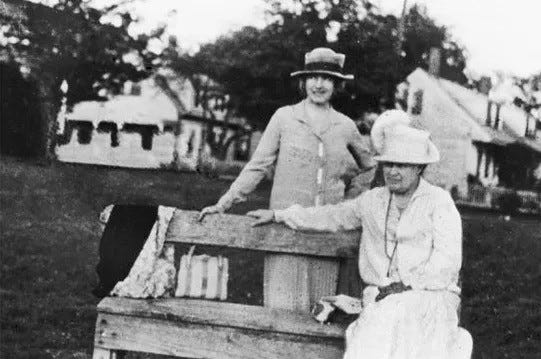

In 1899, Cather met Isabelle McClung, a Pittsburgh socialite, who appears to have been the first woman to return Cather’s affections. Their relationship developed into a life-long friendship, including two years in which Cather lived in the large McClung family home. Throughout the remainder of their lives, they frequently corresponded as McClung became both a source of encouragement and an emotional muse for Cather, igniting a creative spark within her.

In the summer of 1903, Cather visited family and friends in Nebraska. While there, she met with Sarah Harris, the publisher of the Lincoln Courier, who introduced her to Edith Lewis. A few months later, Cather moved to New York City, taking a position at McClure’s Magazine and visiting Lewis, who moved there after college. In 1908, they moved in together, forming a personal and professional relationship, and remained together for the next four decades.

Although Cather needed to escape the West to find her way as a writer, her roots were firmly planted in the frontier, and she visited her parents in Nebraska every year until they died. Despite making her home in the city, the emotional tug of war between East and West lasted her entire life, and she continually returned to the frontier in her memory and writing.

Sarah Orne Jewett wrote to Cather in December 1908, “Your Nebraska life, - a child’s Virginia, and now an intimate knowledge of what we are please to call ‘the Bohemia’ of newspaper and magazine office life” provided Cather with a unique perspective to write from. She continued, “To work in silence and with all one’s heart, that is the writer’s lot; he is the only artist who must be a solitary and yet needs the widest outlook on the world. You must find your own quiet centre of life, and write from that to the world…in short, you must write to the human heart, the great consciousness that all humanity goes to make up.”

At home in NYC, life settled into a routine of writing and participation in the social and cultural scene. She published poetry and short story collections, followed quickly by her first novel, Alexander’s Bridge, which focused on the high society she had come to know through her social connections.

In 1913, Cather published O Pioneers!, the novel that made her name and established her as an authentic voice of the American frontier. In telling the story, she utilized a traditional love plot subverted by a strong female character defying the expectations imposed on her, a style of writing that became standard in her later works. In O Pioneers!, the protagonist married later in life and never had children. In contrast, her relationship with the land was one of renewal, youth, passion, and creativity, provoking imagery of a marriage bed and procreation. In a letter to her friend Elizabeth Sergeant, in which they discussed the book, Cather said, “The country insisted on being the hero of the story and I did not interfere.”

Cather developed her full potential once she made her feelings for the land a part of her art. In one interview, she said, “Most of the basic material a writer works with is acquired before the age of fifteen.” Her first-hand experience made her critical of the myth of the frontier. She focused on reality rather than the idealized version, hoping her novels would correct the record by providing a clearer picture of pioneer life. She could see the world as it truly is, and although she often wrote romanticized plots, the underlying theme was one of harsh reality. Cather treasured a relationship with the earth, and her most despicable characters were self-serving with no love for the land.

Cather incorporated the reversal of gender roles into her writing through stories of men seeking comfort from the women in their lives and stories where women saved men. My Ántonia, her most famous and well-beloved novel, was published in 1918. The narrator is Jim Burden, a young male romantic who falls in love with Ántonia Shimerda, a young Bohemian girl he tutors. Cather avoids the romance plot when Ántonia defies the path expected of her and lays her course through life.

Cather fell out with her publisher when they restricted her creative ownership of her work. She switched to Alfred Knopf in 1920, revolutionizing her career. Knopf was a young and eager publisher who believed strongly in Cather’s independence, giving her complete creative control over her work. They became lifelong friends, and he became her most vigorous advocate, safeguarding her legacy.

Cather found commercial success with the publication of One of Ours, which later won the Pulitzer Prize. Fame brought increasing demands on her time, a fact she did not appreciate. Cather and Lewis hired a personal secretary to manage their schedule and act as gatekeeper to prevent unnecessary intrusions on their creative time. They also purchased a summer cottage on Grand Mann Island, New Brunswick, which provided a place to retreat for privacy.

In April 1923, she published an essay in The New Republic explaining her writing technique, which she called Novel dèmeublè. She described this as a style “stripped of furnishings” while using suggestion and nuance to reach unspoken layers of meaning.

“Whatever is felt upon the page without being specifically named there – that, it seems to me, is created. It is the inexplicable presence of the thing not named, of the overture divined by the ear but not heard by it, the verbal mood, the emotional aura of the fact or the thing or the deed, that gives high quality to the novel or the drama, as well as to poetry itself.”

Over the next 25 years, Cather wrote prolifically, eventually publishing 12 novels, six volumes of short fiction, and two poetry collections. She also contributed widely to newspapers, magazines, and journals, resulting in a productive, lengthy, and consistent career filled with experimentation. She believed art was a path to growth, and although she was a private person, she wrote openly about the world as she saw it. Cather was an ambitious and intelligent writer who lived a life absent of the standard vices found among the literati - alienation, scandal, and alcoholism held no sway over her. She was also very protective of her work. Following the disastrous result of turning her novel, A Lost Lady, into a film, she stipulated in her will that no adaptations of her works could ever be produced.

Seen as a poetic writer emphasizing scene rather than plot, her minimalistic and elegiac style focuses on nostalgia, exile, yearning, desire, and a strong attachment to place. She was an apolitical writer who did not attempt to affect social change but was concerned with how ideologies are codified. She was concerned that dominant cultures try to mold their time's values and moral norms while subordinate cultures attempt to assert their reality.

Readers and writers have consistently appreciated Cather for more than a century. However, it wasn’t until the late 1900’s that academics and scholars acknowledged her canonical status among the greatest writers in American Literature.

Cather died on April 24, 1947. She is buried in New Hampshire beside her lifelong companion, Edith Lewis.

Resources

https://willacather.org

https://cather.unl.edu

Adams, J. R. (2011). Secreted Behind Closed Doors: Rethinking Cather's Adultery Theme and "Unfurnished" Style in My Mortal Enemy. https://core.ac.uk/download/71973515.pdf

Bloomquist, K. M. (2012). American Women Writers, Visual Vocabularies, and the Lives of Literary Regionalism. https://core.ac.uk/download/233208240.pdf

Bohlie, L. B. (1986). Willa Cather in Person: Interviews, Speeches, and Letters.

Have you read anything by Willa Cather? Did you enjoy her work? Which were your favorites? I’m looking forward to hearing from you in the comments.

Recently I enjoyed reading:

- explores the life and scholarship of Eileen Power.

- examines how distraction is destroying art.

I love the notion that writers, and perhaps many creatives, have acquired most of their material—themes, even?—by their adolescent years. I can see this pattern in my own work. Age and a little wisdom gained along the way provide vision and tools to undo the knots in those life threads.

A nice introduction to Willa Cather. I first discovered Cather as a college sophomore and followed that interest to a PhD. If you've not discovered the Willa Cather Archive, it is a wonderful repository of her works, scholarship about her works, and many other primary research materials, such as her letters and photographs.

https://cather.unl.edu/

While Cather hated political activism, her work is unavoidably political. Certainly her racism complicates contemporary readings. But there is no doubt that she was a political conservative, and this sensibility shapes works like Death Comes for the Archbishop and Shadows on the Rock.

One factual correction: Cather died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

One of my favorite Cather novels is Lucy Gayheart. It's a lesser known work, but still resonates deeply. Here is one of my essays about it.

https://joshuadolezal.substack.com/p/how-do-you-know-if-your-eureka-moments