The Bewitching of Queen of Aeaea

The Odyssey Book 10

Exploring Life through the Written Word

"And I debated, my great heart pounding—should I leap from the decks and drown myself at sea or grit my teeth and bear it, stay among the living? I stayed, I bore it all, but buried deep, clinging hard to the decks while the roaring winds swept our squadron back to the island of Aeolus."

Dear friends,

Book 10 of Homer's The Odyssey presents two of the most psychologically complex episodes in Odysseus's long journey home: his encounter with Aeolus, the wind king, and his harrowing experience on Circe's island. These parallel narratives explore themes of divine favor, human weakness, leadership challenges, and the thin line between civilization and barbarism that will resonate throughout the remainder of the epic.

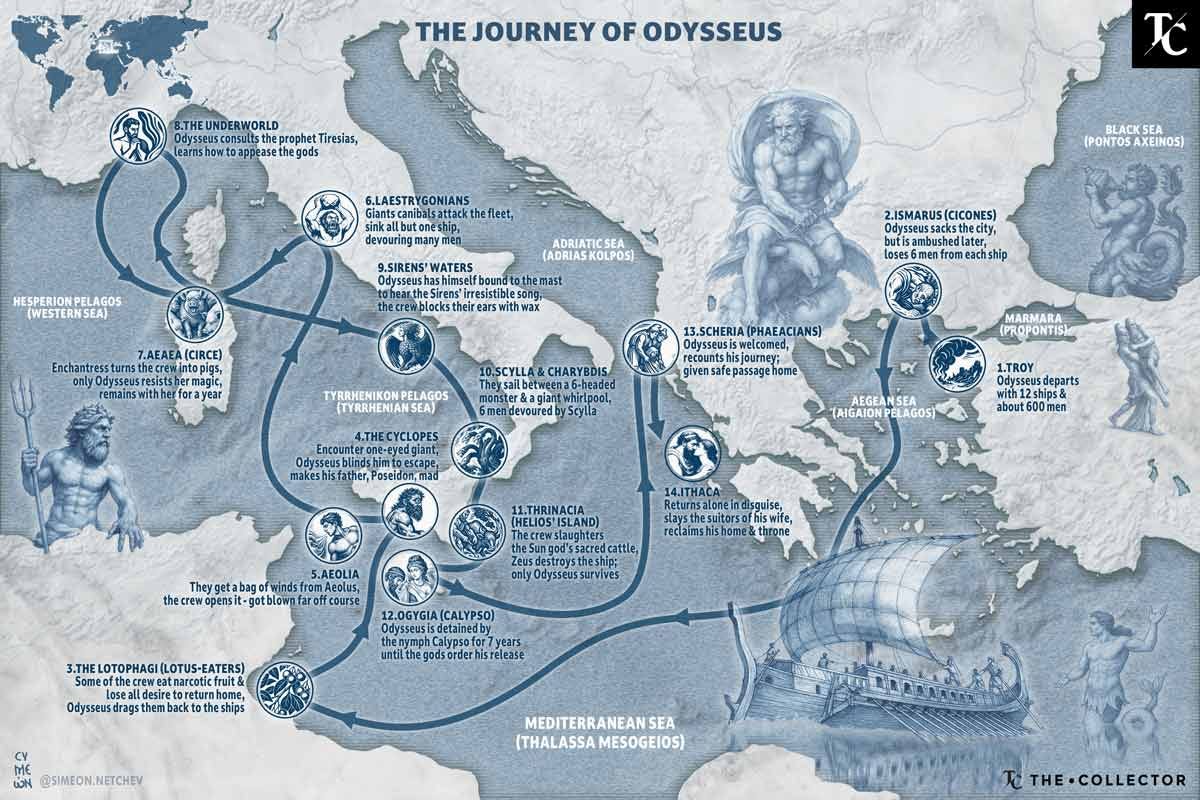

The book opens with Odysseus and his men arriving at the floating island of Aeolia, ruled by Aeolus, keeper of the winds. This divine figure welcomes the travelers with remarkable hospitality, entertaining them for a full month while listening to tales of the Trojan War. When the time comes for departure, Aeolus bestows upon Odysseus what appears to be the perfect gift: all the contrary winds sewn up in an ox-hide bag, leaving only the favorable west wind free to carry the ships safely home to Ithaca. The gesture represents divine intervention at its most benevolent, offering Odysseus a clear path to end his wandering.

For nine days and nights, Odysseus maintains vigilant control over the precious bag, refusing sleep as his ships sail steadily toward home. The sight of Ithaca's familiar shores finally appears on the horizon, so close that the travelers can see the beacon fires burning on the beaches. At this moment of triumph, when home seems within grasp, Odysseus finally succumbs to exhaustion and falls asleep. His men, who have been nursing suspicions about the mysterious bag throughout the voyage, convince themselves that it contains treasure their leader is withholding from them. In a moment of fatal curiosity and greed, they untie the bag.

The consequences are immediate and catastrophic. The imprisoned winds burst forth in a violent tempest that seizes the ships and hurls them back across the sea, undoing nine days of progress in a matter of hours. Odysseus awakens to find his fleet being driven back toward Aeolia, his hopes of homecoming shattered by his men's betrayal and his own moment of human weakness. When they reach Aeolus again, the wind king's attitude has transformed completely. Interpreting the disaster as evidence that Odysseus is cursed by the gods, Aeolus refuses any further assistance and banishes them from his island, declaring that he will not help someone who has clearly fallen from divine favor.

Devastated and now forced to rely on rowing rather than favorable winds, the fleet continues its journey until they reach the land of the Laestrygonians. What initially appears to be another opportunity for rest and resupply quickly transforms into the expedition's darkest hour. When Odysseus sends scouts to investigate this new land, they discover that the Laestrygonians are not merely hostile—they are cannibalistic giants. The reconnaissance party encounters the king's daughter at a well, and she leads them to the royal palace, where the queen proves to be a monstrous figure "huge as a mountain peak." The king, Antiphates, immediately seizes one of the scouts and prepares to devour him.

The surviving scouts flee back to the ships with news of the horrific discovery, but it is too late to escape undetected. The Laestrygonians mass at the harbor entrance and begin hurling massive boulders down at the trapped fleet. The ships are crushed like toys, their crews speared like fish as they struggle in the water. In this nightmarish scene, eleven of Odysseus's twelve ships are destroyed, and hundreds of his men are killed or captured for the giants' feast. Only Odysseus's own ship, which he had prudently anchored outside the harbor rather than within it, manages to escape the massacre.

The survivors sail onward in their single remaining vessel, traumatized by the loss of their comrades and the realization of how precarious their situation has become. They reach Aeaea, the island home of the goddess Circe, where they anchor in a protected cove. For two days, Odysseus and his men remain on the beach, paralyzed by grief and exhaustion, afraid to venture inland after their recent catastrophic encounters.

Finally, Odysseus climbs to a high vantage point and spots smoke rising from the island's interior, indicating human habitation. When he returns to his men with this news, they react with terror rather than hope, remembering the deceptive appearances of the Laestrygonians. Recognizing his crew's psychological fragility, Odysseus divides his remaining men into two groups. He leads one group himself, while his lieutenant Eurylochus takes command of the other. They draw lots to determine which group will investigate the source of the smoke, and fate selects Eurylochus's party.

The scouting party discovers a magnificent palace in a forest clearing, surrounded by wolves and lions who behave with unnatural docility, approaching the men like friendly dogs rather than wild predators. These beasts are, unknown to the explorers, men who have been transformed by Circe's magic, retaining enough of their human nature to recognize and pity their fellow mortals. From within the palace comes the sound of beautiful singing, and the men call out to announce their presence. Circe emerges, radiantly beautiful and welcoming, inviting them inside for a feast.

All of the men accept her hospitality except Eurylochus, whose survival instincts warn him that something is amiss. From his hiding place outside the palace, he watches in horror as Circe mixes her feast with magical drugs and then touches each guest with her wand, transforming them into swine. The men retain their human consciousness and memories, making their transformation all the more agonizing, but they are trapped in animal bodies and driven into pens like livestock.

Eurylochus flees back to the ship to report the disaster to Odysseus, though he is initially so traumatized that he can barely speak coherently. When he finally manages to convey what has happened, he begs Odysseus to abandon the transformed men and sail away immediately, arguing that any attempt at rescue will only result in more casualties. Odysseus rejects this counsel, declaring that he cannot abandon his comrades, and sets out alone toward Circe's palace.

As Odysseus makes his way through the forest, he encounters Hermes, the messenger god, who appears in the form of a handsome young man. Hermes warns Odysseus about Circe's power and provides him with a magical herb called moly, described as having a black root and milk-white flower. This divine plant will protect him from Circe's transformative magic, but Hermes also provides crucial tactical advice: when Circe strikes him with her wand and fails to transform him, Odysseus must draw his sword and threaten her life, forcing her to swear a binding oath that she will not harm him.

Following Hermes' guidance, Odysseus proceeds to the palace, where Circe welcomes him with the same beautiful hospitality she showed his men. She prepares a magnificent feast laced with her magical drugs, but when she touches him with her wand, the moly protects him from transformation. Circe recoils in shock, recognizing that her magic has failed, and Odysseus follows Hermes' instructions by drawing his sword and demanding her submission. Impressed by his resistance to her power and recognizing him as the hero of Troy whose coming had been prophesied, Circe immediately capitulates and swears the sacred oath to do him no harm.

Literary Analysis

Book 10 of The Odyssey operates on multiple symbolic levels, creating a complex meditation on the relationship between divine will and human choice that would have resonated deeply with Homer's original audience and continues to speak to contemporary readers. The structure of the book itself reflects the precarious balance between divine favor and human fallibility that defines the human condition in the Homeric worldview.

The episode with Aeolus functions as a masterclass in dramatic irony, where the audience understands the full tragedy of the situation even as the characters remain blind to their fate. Aeolus's gift represents divine grace in its purest form—unearned favor that offers a direct solution to Odysseus's fundamental problem. The west wind that will carry him home is literally the breath of the gods, while the bag containing the adverse winds represents the cosmic forces that have been working against his return. By neutralizing these opposing elements, Aeolus essentially offers to suspend the natural order of cause and effect that has governed Odysseus's journey thus far.

The psychological complexity of Odysseus's response to this gift reveals Homer's sophisticated understanding of leadership and human nature. For nine days and nights, Odysseus maintains absolute vigilance, refusing to delegate responsibility for the wind bag to anyone else. This behavior reflects both admirable dedication and a fatal flaw in his leadership style—his inability to trust his men with crucial information. Homer presents this as a moment where Odysseus's greatest strengths as a leader become the source of his downfall. His legendary cunning and self-reliance, which have served him so well in other situations, create the conditions for disaster by fostering suspicion and resentment among his crew.

The men's decision to open the bag represents more than simple greed or curiosity—it reflects the breakdown of trust between leader and followers that occurs when communication fails. Their assumption that the bag contains treasure speaks to their fundamental misunderstanding of their situation and their leader's priorities. They cannot conceive that Odysseus would value anything more than material wealth, revealing how far they have drifted from understanding the true nature of their quest for homecoming. The tragic irony is that they destroy the very thing they are all seeking in their attempt to claim what they believe they deserve.

The transformation of Aeolus from benevolent host to rejecting judge illustrates the precarious nature of divine favor in the ancient Greek worldview. The wind king's interpretation of the disaster as evidence of divine curse reflects the belief that the gods' attitudes toward mortals could shift rapidly based on their actions. This theological framework places enormous responsibility on human beings to maintain divine favor through proper behavior, while simultaneously acknowledging that the gods' will can be mysterious and their favor withdrawn for reasons that may seem arbitrary to mortal understanding.

The Laestrygonian Massacre and the Fragility of Civilization

The Laestrygonian episode serves as perhaps the darkest moment in the entire Odyssey, presenting a world where the normal rules of civilization—hospitality, communication, and basic humanity—have been completely inverted. Homer's description of these cannibalistic giants creates a powerful contrast with the civilized societies that Odysseus has previously encountered, forcing both the hero and the audience to confront the thin line that separates civilization from barbarism.

The initial reconnaissance follows the standard pattern of ancient exploration—scouts are sent ahead to gather information about potentially hostile populations before the main force commits to landing. The discovery of the king's daughter at the well initially seems promising, as it suggests a normal human society with typical gender roles and social structures. However, Homer quickly subverts these expectations when the daughter leads the scouts not to safety but to their doom, revealing that even the most fundamental social bonds—parental protection, hospitality toward strangers, basic human empathy—have been corrupted in this society.

The figure of the Laestrygonian queen, described as "huge as a mountain peak," represents a monstrous inversion of the ideal of feminine beauty and hospitality that pervades Greek culture. Where Greek women were expected to welcome guests and provide for their needs, the Laestrygonian queen embodies pure appetite and destructive power. Her monstrous size emphasizes the supernatural nature of the threat while also suggesting that this society represents a regression to a pre-civilized state where physical power determines all social relationships.

The tactical details of the Laestrygonian attack demonstrate Homer's understanding of naval warfare and his ability to create tension through realistic military description. The giants' strategy of blocking the harbor entrance before beginning their assault shows sophisticated tactical thinking, while their method of crushing the ships with boulders hurled from above reflects their supernatural strength. The image of the crews being "speared like fish" creates a horrific reversal of the normal relationship between human beings and their food sources, emphasizing the complete breakdown of natural order in this encounter.

Odysseus's decision to anchor his ship outside the harbor rather than within it proves to be the crucial factor in his survival. This tactical choice reflects his growth as a leader and his increasing wariness after previous disasters, but it also highlights the random nature of survival in a hostile world. The fact that he alone thought to take this precaution while his other captains did not suggests either superior foresight or simple chance—the text leaves this ambiguity unresolved, allowing readers to debate whether Odysseus's survival represents divine favor, superior judgment, or mere luck.

Circe's Island and the Transformation of Identity

The Circe episode operates on multiple allegorical levels, addressing questions of identity, temptation, and the relationship between human consciousness and physical form that have fascinated readers for millennia. Circe herself represents one of the most complex divine figures in the Odyssey, embodying both the danger and the potential salvation that divine power represents for mortal beings.

The transformation of Odysseus's men into swine functions as a powerful metaphor for the loss of human dignity and rational thought. Homer emphasizes that the men retain their human consciousness while trapped in animal bodies, creating a psychological horror that transcends simple physical transformation. This detail transforms the episode from a straightforward tale of magical punishment into a profound meditation on what constitutes human identity and whether consciousness alone is sufficient to maintain human dignity when separated from human form.

The behavior of the previously transformed men—the wolves and lions who approach the newcomers with unnatural friendliness—suggests that Circe's magic does not simply turn humans into animals but rather strips away the social conditioning and rational thought that separate civilized humans from their bestial impulses. These creatures retain enough human memory to recognize and pity their fellow mortals, but they lack the capacity for speech or complex action that would allow them to warn the newcomers of their danger.

Eurylochus's refusal to enter Circe's palace demonstrates the survival value of suspicion in a world where appearances consistently deceive. His decision to remain outside while his companions accept Circe's hospitality reflects hard-won wisdom about the danger of trusting too readily in apparent kindness. However, his later counsel to abandon the transformed men and flee the island reveals the limitations of pure pragmatism. While his caution saves him from transformation, his willingness to abandon his comrades reflects a different kind of moral transformation—the loss of the loyalty and solidarity that bind human communities together.

The intervention of Hermes and the gift of the moly plant represent divine assistance of a very different kind from Aeolus's earlier favor. Where Aeolus offered to remove obstacles from Odysseus's path, Hermes provides the tools necessary for Odysseus to overcome challenges through his own effort. The moly plant functions as a symbol of divine grace that empowers human agency rather than replacing it. Hermes' tactical advice about drawing his sword on Circe emphasizes that even with divine protection, Odysseus must be prepared to act decisively and courageously to achieve his goals.

Historical Context and Ancient Greek Values

Book 10 reflects several key concerns of ancient Greek society, particularly regarding the nature of divine justice, the obligations of hospitality, and the challenges of leadership in a world where survival depends on maintaining the favor of unpredictable supernatural forces. The concept of xenia (guest-friendship) that governs much of the Odyssey is both upheld and violated in complex ways throughout this book, revealing the tensions inherent in this crucial social institution.

Aeolus represents the ideal of divine hospitality, entertaining his guests for a month without asking for anything in return and providing them with a gift that should ensure their safe journey home. His later rejection of Odysseus after the disaster with the wind bag reflects the ancient Greek understanding that hospitality creates mutual obligations—guests must prove themselves worthy of continued favor through their actions. The wind king's interpretation of the accident as evidence of divine curse reflects the belief that the gods' attitudes toward mortals are revealed through their fortunes, creating a theological framework where success and failure are read as signs of divine approval or disapproval.

The Laestrygonian episode inverts every expectation of proper hospitality, creating a society where strangers are viewed not as guests to be honored but as prey to be consumed. This inversion would have been particularly shocking to Homer's original audience, for whom the institution of xenia represented one of the fundamental pillars of civilized society. The cannibalistic giants represent not just physical danger but the complete breakdown of the social bonds that make human community possible.

Circe's initial behavior follows the proper forms of hospitality—she welcomes strangers, provides them with food and drink, and offers them shelter. However, her use of magical drugs to transform her guests represents a profound violation of the trust that hospitality is supposed to create. Her later transformation into a helpful ally after being conquered by Odysseus reflects the ancient Greek understanding that divine beings could shift their attitudes toward mortals based on demonstrations of worthiness or power.

The role of divine intervention in human affairs, represented by both Aeolus and Hermes, reflects the complex relationship between fate and free will in ancient Greek thought. The gods provide opportunities and tools, but human beings must still make choices and take actions that determine their ultimate fate. The contrast between Aeolus's gift, which required only passive reception, and Hermes' aid, which demanded active courage and tactical skill, illustrates different models of divine assistance and human agency.

Contemporary Relevance and Universal Themes

The psychological and moral challenges presented in Book 10 continue to resonate with contemporary readers because they address fundamental aspects of human nature and social organization that transcend historical periods. The breakdown of trust between Odysseus and his men over the wind bag speaks directly to modern concerns about leadership, communication, and the destructive power of suspicion in organizations and relationships.

The episode illustrates how even well-intentioned leaders can create the conditions for disaster through their inability to delegate authority or share crucial information with their followers. Odysseus's decision to maintain sole control over the wind bag, while understandable given its importance, creates a situation where his men's natural curiosity and sense of exclusion leads to catastrophic consequences. This dynamic appears repeatedly in contemporary contexts where leaders' inability to trust their subordinates with important information breeds resentment and ultimately undermines the very goals the secrecy was meant to protect.

The transformation of the men into swine on Circe's island offers a powerful metaphor for how human beings can lose their essential humanity through various forms of addiction, obsession, or moral compromise. The detail that the transformed men retain their human consciousness while trapped in animal bodies speaks to contemporary understanding of how people can become prisoners of their own destructive behaviors while remaining aware of their situation. The image of rational beings trapped in forms that prevent them from acting on their reason resonates with modern psychological insights about the relationship between consciousness and behavior.

The Laestrygonian massacre confronts readers with the reality of societies where normal moral constraints have completely broken down. While literal cannibalism may seem like an ancient concern, the episode's exploration of how civilized norms can collapse under extreme circumstances speaks to contemporary anxieties about social breakdown, ethnic conflict, and the potential for ordinary human beings to commit acts of extraordinary brutality when social institutions fail to maintain order.

The theme of divine favor and its withdrawal, represented in the contrasting attitudes of Aeolus before and after the wind bag incident, reflects contemporary concerns about how quickly circumstances can change and how success can breed the conditions for its own reversal. The wind king's interpretation of Odysseus's misfortune as evidence of divine curse mirrors modern tendencies to read failure as evidence of fundamental character flaws rather than the result of complex interactions between personal choices and external circumstances.

The role of chance and timing in determining outcomes—from Odysseus's moment of fatigue after nine days of vigilance to his tactical decision to anchor outside the Laestrygonian harbor—speaks to contemporary understanding of how random factors can have enormous consequences in human affairs. The book's exploration of how small decisions can have cascading effects resonates with modern complexity theory and systems thinking about organizational and social dynamics.

Perhaps most significantly, Book 10's examination of the relationship between individual agency and external forces continues to speak to fundamental questions about human responsibility and the extent to which people can control their own destinies. The contrast between situations where characters have meaningful choices and those where they are subject to forces beyond their control reflects ongoing debates about free will, determinism, and moral responsibility in contemporary philosophy and psychology.

The book's portrayal of leadership challenges, from communication breakdowns to the difficulty of maintaining morale in the face of repeated disasters, offers insights into contemporary organizational and political leadership. Odysseus's evolution as a leader—from the overconfident hero who relies primarily on his own cunning to the more cautious and collaborative leader who learns to accept divine assistance—reflects universal patterns of leadership development that remain relevant in contemporary contexts.

Study Questions

Leadership and Trust: Odysseus's decision to keep the contents of Aeolus's wind bag secret from his men ultimately leads to disaster, while his later willingness to accept Hermes' guidance proves successful. How does Book 10 explore the relationship between secrecy and leadership effectiveness? What does this suggest about when leaders should share information with their followers and when they should seek advice from others?

Divine Justice and Human Agency: The contrast between Aeolus's initial generosity and later rejection raises questions about the nature of divine justice in the epic. To what extent are the disasters that befall Odysseus and his men the result of divine displeasure, and to what extent do they stem from human choices and character flaws? How does Homer balance fate and free will in these episodes?

Transformation and Identity: The transformation of men into animals on Circe's island serves as a powerful metaphor for the loss of human dignity and rational thought. What does Homer suggest about the relationship between physical form and human identity? How do the various transformations in Book 10—from the wind bag disaster to the literal transformation into swine—illuminate different ways that human beings can lose their essential humanity?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 11. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled The Kingdom of the Dead and spans pages 249-270. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled The Dead and spans pages 279-300.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you've found value in my work and it has helped, informed, or entertained you, I'd be grateful if you'd consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue creating content and means more than you know. Even small contributions make a real difference and allow me to keep sharing my work with you. Thank you for reading and for any support you're able to offer.

Affiliate links: You can click on the title of any book mentioned in this article to purchase your own copy. These are affiliate links, earning me a very small commission for any purchase you make.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

"Homer presents this as a moment where Odysseus's greatest strengths as a leader become the source of his downfall. His legendary cunning and self-reliance, which have served him so well in other situations, create the conditions for disaster by fostering suspicion and resentment among his crew."

Matt, there's a huge implication here. That context always matters. And that our greatest strengths in one context can become our greatest weaknesses in another. It's why leaders can't blindly lean on their strengths in all situations without considering how those strengths may actually be counterproductive in the moment.

Such great lessons from this classic!

-Jenks

As ever such great insights into the greater meanings and depth of The Odyssey. It is a book I love to return to especially in the summer.

Years ago when first reading it, and around it I came across a fascinating book: The Ulysses Voyage; Sea Search for the Odyssey by Tim Severin pub 1987. He recreates the voyage in a replica of a Bronze Age galley, sailed by using navigational rules of the time and attempting to find the locations for real. He did a similar voyage following Jason. I am familiar with the Western coast of Greece so find his discoveries and theories fascinating as well as bringing The Odyssey to life for me. Worth seeking out a copy in my opinion.

By this part of the epic his theories are so different from those who place the wanderings of Odysseus across the Mediterranean. His are far closer to Ithaca itself.