The Cattle of the Sun

The Odyssey Book 12

Exploring Life through the Written Word

"Come closer, famous Odysseus—Achaea's pride and glory—moor your ship on our coast so you can hear our song! Never has any sailor passed our shores in his black craft until he has heard the honeyed voices pouring from our lips, and once he hears to his heart's content sails on, a wiser man. We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once endured on the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all!"

Dear friends,

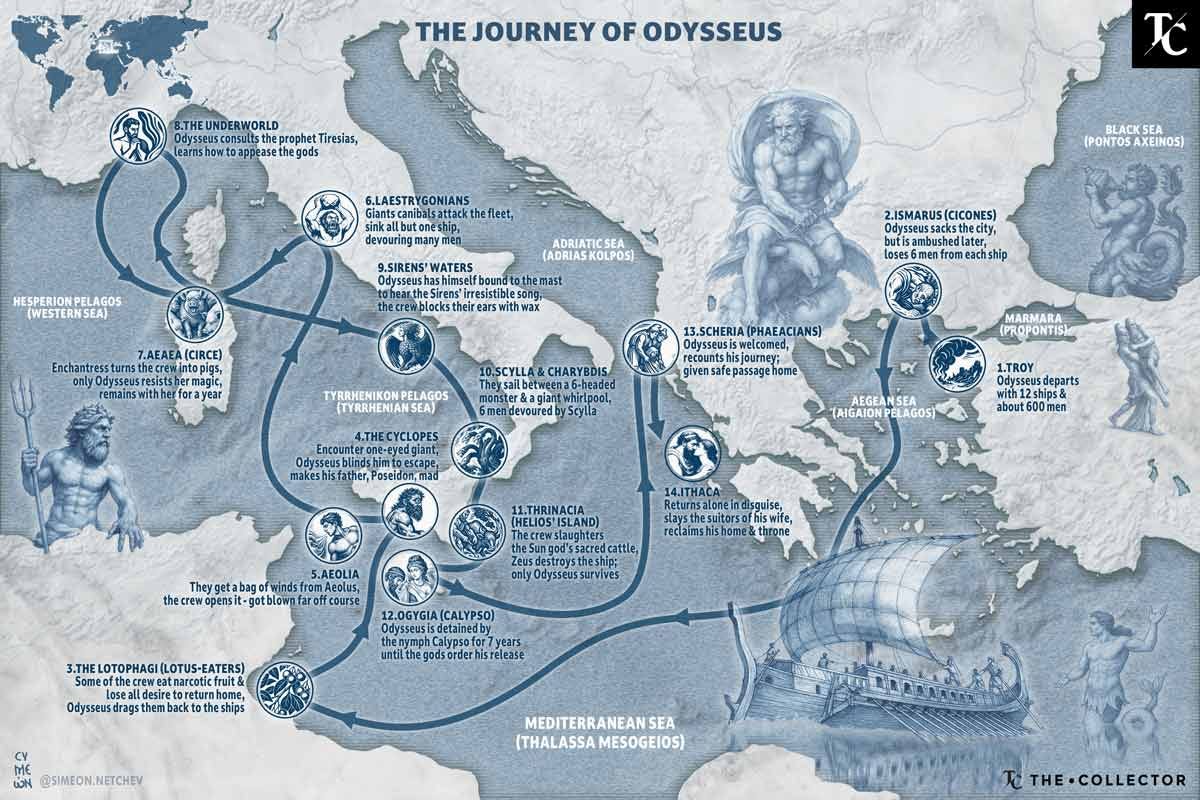

Book 12 of Homer's The Odyssey brings Odysseus's supernatural wanderings to their devastating climax, presenting a series of increasingly dangerous trials that test not only his cunning and courage but his ability to balance divine warnings with human limitations. This book transforms the hero from the leader of a fleet into a sole survivor, stripping away his companions and ships to leave him entirely dependent on divine mercy and his own resourcefulness. The chapter operates as a crucible where all of Odysseus's previous experiences are tested against ultimate temptation and divine prohibition.

The book opens with Odysseus and his men returning to Circe's island to fulfill their promise to Elpenor, whose unburied shade had pleaded for proper funeral rites during their visit to the underworld. This return journey demonstrates Odysseus's growing understanding of his obligations to the dead and represents a significant development in his character—the impulsive hero who once valued personal glory above all else now recognizes duties that transcend immediate self-interest. Circe welcomes them back and helps conduct Elpenor's funeral, building a proper pyre and barrow while his comrades perform the ritual lamentations that will give his spirit rest.

During this return visit, Circe takes Odysseus aside for a private consultation that will prove crucial to his survival. Having learned of his journey to the underworld and his consultation with Tiresias, she provides detailed tactical advice about the supernatural dangers that lie ahead. Her warnings are more specific and practical than the prophet's general admonitions, offering concrete strategies for surviving encounters that have destroyed countless other heroes. This conversation represents a key moment in the epic where divine assistance takes the form of actionable intelligence rather than mysterious prophecy.

Circe first describes the Sirens, whose irresistible song lures sailors to their deaths on the rocky shores of their island. These creatures possess knowledge of everything that happens on earth, making their song not merely beautiful but informationally irresistible to mortals hungry for understanding. The goddess explains that the bones of their victims litter the beach around their flowery meadow, creating a grotesque contrast between beauty and death that characterizes many of the supernatural threats in Odysseus's world. Circe's solution requires Odysseus to choose between personal experience and communal safety: he can hear their song if his men bind him to the mast and stop their own ears with wax, but he must accept physical restraint and the torment of being unable to respond to their call.

The goddess then describes the far more deadly choice that awaits beyond the Sirens: the passage between Scylla and Charybdis. Scylla is a six-headed monster who lives in a cave high on one side of a narrow strait, each head capable of snatching a sailor from any ship that passes too close. Charybdis is a massive whirlpool on the opposite side that sucks down entire ships three times daily before spewing the wreckage back to the surface. Circe makes it clear that no ship can pass through this strait without loss—the only choice is between losing six men to Scylla or losing everyone to Charybdis. She counsels Odysseus to stay close to Scylla's cliff and accept the loss of six men rather than risk total destruction in the whirlpool.

Finally, Circe warns about the island of the Sun God, where Helios keeps his sacred cattle. These immortal animals must not be harmed under any circumstances—to kill them would bring divine wrath that will destroy Odysseus's ship and crew, leaving him to complete his journey home alone after years of additional wandering. The warning echoes Tiresias's prophecy but adds urgency and specificity: if they can resist the temptation to slaughter the cattle for food, they might yet reach home safely together.

Armed with these warnings, Odysseus and his men set sail toward their final trials. As they approach the Sirens' island, Odysseus reveals Circe's plan to his crew, but significantly, he conceals her prophecy about the inevitable losses at Scylla and Charybdis. This decision reflects his growing sophistication as a leader—he understands that some knowledge would paralyze his men rather than help them. The crew dutifully stops their ears with softened beeswax and binds Odysseus securely to the mast, leaving him free to hear but unable to act on what he hears.

The encounter with the Sirens becomes a supreme test of intellectual curiosity versus survival wisdom. As their ship approaches, the Sirens begin their song, addressing Odysseus by name and promising to reveal all the secrets of the Trojan War and everything that will happen on earth. Their temptation is not merely aesthetic—they offer the ultimate intellectual satisfaction, complete knowledge and understanding. Odysseus's response is immediate and overwhelming; he struggles against his bonds and signals frantically for his men to release him. However, his companions, following his earlier instructions, only bind him more tightly and row harder to escape the island's influence.

The psychological torture that Odysseus endures during this passage represents one of the most sophisticated explorations of temptation in ancient literature. He experiences the full force of desire for forbidden knowledge while being physically prevented from acting on that desire. The scene demonstrates how wisdom sometimes requires accepting ignorance and how survival may depend on embracing limitations rather than pursuing unlimited experience. When they finally pass beyond the Sirens' range, Odysseus's men release him, but the text suggests that he remains haunted by the knowledge he was denied.

The approach to Scylla and Charybdis confronts Odysseus with the most terrible leadership decision of his entire journey. Following Circe's advice, he steers closer to Scylla's cliff, knowing that this choice will cost six of his men their lives. He does not share this knowledge with his crew, recognizing that such information would create panic and possibly lead to worse outcomes. As they enter the strait, the men are first terrified by the sight and sound of Charybdis sucking down the sea, creating a whirlpool so massive and violent that it seems capable of destroying the world itself.

While the crew focuses their attention and terror on Charybdis, Scylla strikes with horrific efficiency. Six of Odysseus's best men are snatched from the deck by the monster's heads and carried up to her cave, where they are devoured while still calling out Odysseus's name. The hero describes this as the most pitiful sight he witnessed in all his wanderings on the sea, emphasizing the personal anguish of being forced to sacrifice his own men to save the rest. The scene represents the ultimate test of command responsibility, where leadership requires making choices that ensure survival at the cost of individual lives.

The successful passage through the strait brings the survivors to Thrinacia, the island of the Sun God, where Helios keeps his sacred cattle. Despite Odysseus's urgent warnings about the divine prohibition against harming these animals, his men insist on landing to rest and take on provisions. Odysseus extracts a solemn oath from all of them that they will not touch the cattle, but their promise proves worthless when circumstances test their resolve.

Initially, the landing seems harmless enough. The men beach their ship in a sheltered cove and set up camp, carefully avoiding the sacred herds that graze openly across the island. However, adverse winds trap them on the island for a full month, and their provisions gradually run out. As hunger begins to dominate their thoughts, the sight of the fat, beautiful cattle becomes increasingly unbearable. Odysseus recognizes the growing danger and spends much of his time in solitary prayer, climbing to high places on the island to petition the gods for favorable winds and a safe departure.

During one of these prayer sessions, the gods send Odysseus into an unnatural sleep, removing him from the scene at the crucial moment when divine temptation will test his men's resolve. In his absence, Eurylochus emerges as the voice of rebellion, arguing that starvation is a worse fate than divine punishment and that they should slaughter some cattle to preserve their lives. He reasons that if they survive to reach home, they can build a rich temple to Helios as compensation for their transgression, and if the god prefers to destroy them rather than accept restitution, at least they will die quickly at sea rather than slowly from hunger.

Eurylochus's argument proves persuasive to men weakened by hunger and despair. While Odysseus sleeps, they drive the finest cattle away from the herds and perform an elaborate sacrifice, hoping that proper ritual attention might mitigate their offense. However, the sacrifice itself becomes a supernatural horror show—the meat bellows on the spits, the hides crawl along the ground, and the very air fills with the sound of lowing cattle, as if the slaughtered animals are crying out for divine vengeance.

When Odysseus awakens and smells the roasting meat, he realizes immediately what has happened and understands that their doom is sealed. His prayers to the gods bring no response except silence, confirming that his men have crossed a line from which there can be no return. For six days, the crew feasts on the sacred beef while supernatural omens multiply around them, but they are committed to their course of action and cannot undo what they have done.

On the seventh day, the winds finally shift and allow them to depart the island, but their escape proves to be merely a prelude to divine retribution. As soon as they reach open water, Zeus assembles a massive storm cloud over their ship and strikes it with a thunderbolt. The vessel explodes in a burst of divine fire, filling the air with the smell of sulfur and instantly killing everyone aboard except Odysseus, who is thrown clear of the wreckage.

Alone in the churning sea, Odysseus manages to lash together the ship's mast and keel to create a makeshift raft. However, the winds drive him back toward the strait of Scylla and Charybdis, where he faces the ultimate test of individual survival. As dawn breaks, Charybdis sucks down his makeshift raft, and Odysseus is forced to grab onto the branch of a fig tree that grows over the whirlpool. He hangs there like a bat throughout the entire day, waiting for Charybdis to disgorge the wreckage of his raft so he can retrieve it and continue his journey.

The image of the greatest hero of the age hanging helplessly from a tree branch while cosmic forces rage beneath him represents the ultimate reduction of human pretension. All of Odysseus's cunning, strength, and divine favor have been stripped away, leaving him entirely dependent on patience, endurance, and the hope that the natural cycle of the whirlpool will eventually offer him another chance. When Charybdis finally spits out the mast and keel at evening, Odysseus drops into the water, retrieves his makeshift raft, and paddles desperately away from the strait with his hands.

The book concludes with Odysseus alone on the open sea, his fleet destroyed, his companions dead, and his homecoming reduced to a solitary struggle for survival. For nine days he drifts on his improvised raft until the currents carry him to Calypso's island, where he will remain trapped for seven years before the gods finally arrange for his release. This ending transforms the hero from the leader of an expedition into a lone survivor whose story must continue through entirely different means.

Literary Analysis

Book 12 of The Odyssey is the culmination of Odysseus's supernatural wanderings, presenting a series of trials that systematically strip away his external supports—his ships, his crew, his divine protections—to reveal the essential core of heroic character. The structure of the book creates an escalating pattern of moral complexity, moving from the relatively straightforward challenge of the Sirens through the agonizing choice between Scylla and Charybdis to the ultimate catastrophe of the Cattle of the Sun. Each episode tests different aspects of leadership and moral character, building toward a conclusion that demonstrates how even the greatest heroes must ultimately depend on forces beyond their control.

The return to Circe's island for Elpenor's funeral establishes the book's central theme of obligation and consequence. This episode demonstrates Odysseus's evolving understanding of leadership responsibility—he now recognizes that his duties extend beyond the immediate survival of his expedition to include proper attention to the dead and the fulfillment of promises made in extremis. The funeral rites for Elpenor create a ritual framework that acknowledges loss while providing closure, establishing a model for how communities should process grief and honor their obligations to those who have died in service to collective goals.

Circe's detailed briefing about the dangers ahead represents divine assistance at its most practical and morally complex. Unlike previous divine interventions that offered magical solutions or removed obstacles entirely, Circe's advice forces Odysseus to confront scenarios where loss is inevitable and leadership requires choosing between different types of disaster. Her counsel about the Sirens offers a workable strategy for experiencing forbidden knowledge without being destroyed by it, but her guidance about Scylla and Charybdis presents the fundamental tragic choice that defines mature leadership—the necessity of sacrificing some to save others.

The psychological and moral framework that governs these choices reflects Homer's sophisticated understanding of how knowledge, power, and responsibility interact in situations where perfect solutions do not exist. Circe's warnings create a burden of foreknowledge that makes Odysseus complicit in the losses that follow, while also providing him with the information necessary to minimize those losses. The goddess's advice transforms him from a reactive hero who responds to challenges as they arise into a strategic leader who must plan for acceptable losses while working to achieve overall mission success.

The Sirens and the Temptation of Unlimited Knowledge

The encounter with the Sirens represents one of literature's most sophisticated explorations of intellectual temptation and the relationship between knowledge and wisdom. Homer's description of these creatures transcends simple physical attraction to explore the more fundamental human desire for complete understanding and perfect information. The Sirens' promise to reveal "all that comes to pass on the fertile earth" speaks to the deepest human intellectual ambitions—the desire to transcend the limitations of partial knowledge and achieve godlike understanding of reality.

The specific content of the Sirens' song—their promise to tell Odysseus everything about the Trojan War and all future events—demonstrates Homer's understanding of how intellectual temptation operates. They offer not random knowledge but precisely the information that would be most valuable to their target: complete understanding of the defining experience of his life and perfect foresight about challenges to come. This personalized approach to temptation makes their offer almost irresistible, as it addresses Odysseus's specific intellectual and practical needs.

The physical restraint that enables Odysseus to experience the Sirens' song without being destroyed by it creates a powerful metaphor for how wisdom sometimes requires accepting limitation rather than pursuing unlimited experience. The image of the hero bound to his ship's mast while experiencing overwhelming desire for liberation speaks to fundamental tensions between knowledge and safety, curiosity and wisdom, individual desire and collective survival. The scene suggests that certain forms of knowledge may be intrinsically dangerous to possess, requiring external constraints to prevent self-destruction.

The psychological torture that Odysseus endures during this passage—experiencing complete intellectual desire while being physically prevented from acting on it—represents one of the most penetrating analyses of temptation in ancient literature. Homer's description emphasizes not the beauty of the Sirens' song but its informational content and the agony of being denied access to knowledge that seems within reach. This focus on cognitive rather than sensual temptation elevates the episode from a simple test of self-control to a meditation on the relationship between knowledge and suffering.

The successful passage beyond the Sirens' influence demonstrates the possibility of surviving intellectual temptation through a combination of self-knowledge, external support, and acceptance of limitation. Odysseus's strategy requires him to acknowledge his own weakness while creating structural constraints that prevent that weakness from leading to destruction. The episode suggests that wisdom lies not in eliminating temptation but in developing strategies for managing it when elimination is impossible.

Scylla and Charybdis: The Tragic Calculus of Leadership

The passage between Scylla and Charybdis presents the most morally complex challenge in the entire epic, forcing Odysseus to confront the fundamental tragic dimension of leadership responsibility. The choice between the six-headed monster and the all-consuming whirlpool represents the kind of impossible decision that defines mature leadership—situations where all available options involve significant loss and where the leader's responsibility is to choose the form of disaster that minimizes overall damage.

Circe's advice to accept the loss of six men rather than risk total destruction in Charybdis creates a utilitarian calculus that prioritizes collective survival over individual lives. This counsel forces Odysseus to move beyond heroic idealism—the belief that clever tactics and divine favor can eliminate all risks—toward a more tragic understanding of leadership that acknowledges the inevitability of loss in extreme circumstances. The goddess's guidance transforms leadership from a matter of finding perfect solutions to one of making acceptable compromises with disaster.

Odysseus's decision to conceal this information from his crew reflects his growing sophistication as a leader and his understanding of how knowledge affects group psychology. His recognition that revealing the inevitable sacrifice of six men would create panic and possibly lead to worse outcomes demonstrates tactical wisdom about information management in crisis situations. However, this decision also isolates Odysseus morally, making him alone responsible for choices that affect his followers' lives while denying them the knowledge that might allow them to participate in those decisions.

The actual encounter with Scylla creates one of the most harrowing scenes in ancient literature, as Odysseus must watch six of his best men being devoured while knowing that he chose this outcome over the alternative of total destruction. Homer's description emphasizes both the horror of the individual deaths and Odysseus's psychological anguish at being forced to sacrifice his own men. The detail that the victims call out Odysseus's name as they are carried off to be eaten creates a personal dimension to the tragedy that transcends tactical considerations.

The aftermath of this passage reveals how such choices affect both leaders and survivors. The text suggests that the successful navigation of the strait, while strategically necessary, creates psychological wounds that may never heal completely. Odysseus's description of this as the most pitiful sight in all his wanderings indicates that tactical success can coexist with moral anguish, and that effective leadership sometimes requires accepting responsibility for necessary but devastating choices.

The Cattle of the Sun: Divine Law and Human Limitation

The episode of the Cattle of the Sun represents the ultimate test of human ability to obey divine commands under extreme duress. Unlike previous challenges that tested cleverness, courage, or tactical skill, this trial focuses entirely on the capacity for restraint in the face of life-threatening temptation. The sacred nature of Helios's cattle creates an absolute prohibition that admits no exceptions or compromises—they must not be harmed regardless of circumstances.

The month-long delay on Thrinacia creates the perfect conditions for testing this prohibition, as the crew's initial obedience gradually erodes under the pressure of hunger and despair. Homer's description of the gradual shift from easy compliance to desperate temptation demonstrates his understanding of how extreme circumstances can undermine moral resolve. The crew's initial confidence in their ability to honor their oath gives way to increasing fixation on the forbidden cattle as their situation becomes more desperate.

Eurylochus's argument for violating the divine prohibition reflects a rational calculation that weighs certain death from starvation against possible divine punishment. His reasoning that they can build a temple to Helios as compensation if they survive, or die quickly at sea if they don't, represents an attempt to find a middle ground between absolute obedience and total rebellion. This pragmatic approach to divine law demonstrates how human beings rationalize violations of absolute principles when survival is at stake.

The supernatural horror that accompanies the sacrifice—the bellowing meat, crawling hides, and disembodied lowing—creates a vivid demonstration that some violations of divine law immediately corrupt the natural order. These omens serve as warnings that the crew's transgression has consequences that extend beyond simple punishment to fundamental disruption of cosmic harmony. The grotesque nature of these signs emphasizes that the men have crossed a boundary from which no return is possible.

Odysseus's enforced absence during the crucial decision reflects the gods' manipulation of events to ensure that divine justice operates according to plan. His supernatural sleep removes him from the scene precisely when his leadership might have prevented the disaster, suggesting that the gods have determined that this test must proceed without his intervention. This detail complicates questions of responsibility and agency, as it implies that the crew's failure may have been orchestrated by divine forces rather than resulting purely from human weakness.

Historical Context and Religious Significance

Book 12 reflects central concerns of ancient Greek religious and social thought, particularly regarding the relationship between divine law and human survival, the nature of leadership responsibility, and the cosmic consequences of violating sacred prohibitions. The various supernatural challenges that Odysseus faces represent different categories of divine testing that would have been immediately recognizable to Homer's original audience as reflections of their own religious and moral concerns.

The concept of sacred animals that must not be harmed under any circumstances reflects widespread ancient Mediterranean religious practices that designated certain creatures as belonging specifically to particular deities. The Cattle of the Sun represent this category of absolutely protected beings whose violation brings immediate divine retribution regardless of human necessity or intention. Archaeological evidence suggests that similar prohibitions existed throughout the ancient world, creating sanctuaries and protected species that served as tests of religious obedience.

The figure of Helios as an active divine force whose sacred property must be respected reflects the ancient Greek understanding of natural phenomena as expressions of divine personality and will. The sun god's cattle represent his life-giving power made manifest in the world, and their slaughter constitutes not merely theft but a fundamental attack on the cosmic order that maintains life itself. The immediate divine response to their violation demonstrates the belief that some actions automatically trigger cosmic consequences without requiring deliberate divine judgment.

The Sirens' promise of universal knowledge reflects ancient Greek anxieties about the relationship between human intellectual ambition and divine prerogatives. The belief that certain forms of knowledge were properly reserved for gods created ongoing tension between human curiosity and religious restraint. The Sirens represent the temptation to transcend human limitations through forbidden knowledge, while Odysseus's successful resistance demonstrates the wisdom of accepting appropriate boundaries on human understanding.

The passage between Scylla and Charybdis reflects ancient understanding of leadership as necessarily involving tragic choices where perfect solutions do not exist. The acceptance that good leadership sometimes requires sacrificing some to save others would have resonated with audiences familiar with military and political decision-making in city-states frequently threatened by external enemies. The episode provides a framework for understanding how leaders can remain morally worthy while making choices that result in the deaths of their followers.

The emphasis on proper funeral rites for Elpenor reflects the central importance of death ritual in ancient Greek society and the belief that improper treatment of the dead could have serious consequences for both individuals and communities. The care with which Odysseus fulfills his obligation to his dead follower demonstrates the kind of attention to ritual propriety that was expected of leaders and the understanding that such obligations transcended immediate practical concerns.

Contemporary Relevance and Moral Complexity

The moral and psychological challenges presented in Book 12 continue to resonate with contemporary concerns about leadership, ethical decision-making, and the relationship between knowledge and responsibility. The scenarios that Odysseus faces provide frameworks for understanding modern dilemmas where leaders must make choices involving acceptable losses, manage access to dangerous information, and balance individual rights against collective survival.

The encounter with the Sirens speaks directly to contemporary concerns about information overload, the addictive nature of certain forms of knowledge, and the psychological costs of unlimited access to information. The image of knowledge that is simultaneously irresistible and destructive resonates with modern understanding of how access to certain types of information—from classified intelligence to personal data about others—can create psychological burdens and moral complications that may outweigh the benefits of knowing.

The choice between Scylla and Charybdis provides a framework for understanding contemporary leadership dilemmas where all available options involve significant negative consequences. Modern military, medical, and business leaders frequently face situations where the only choice is between different types of loss, and where leadership effectiveness is measured not by the ability to eliminate risk but by the wisdom to choose acceptable forms of disaster over catastrophic ones.

The episode of the Cattle of the Sun speaks to contemporary debates about absolute moral principles versus situational ethics, particularly in extreme circumstances where survival may conflict with fundamental prohibitions. The crew's decision to violate divine law rather than starve reflects ongoing tensions between universal moral principles and contextual considerations, echoing modern debates about when, if ever, fundamental ethical principles can be suspended in life-threatening situations.

Odysseus's decision to conceal crucial information from his crew during the passage between Scylla and Charybdis reflects contemporary concerns about transparency in leadership and the ethics of withholding information that might affect followers' ability to make informed decisions about their own risks. The episode raises questions about when leaders are justified in making unilateral decisions about acceptable losses and when followers have the right to participate in choices that affect their survival.

The psychological isolation that results from possessing dangerous or burdensome knowledge—both Odysseus's foreknowledge of inevitable losses and his awareness of divine prohibitions that his men may not be able to honor—speaks to contemporary understanding of how information creates moral responsibility and psychological burden. The text explores how knowledge can isolate individuals even within communities and how awareness of future problems can create present suffering.

The gradual erosion of moral resolve under extreme duress, demonstrated in the crew's eventual violation of their oath regarding the sacred cattle, reflects contemporary psychological understanding of how stress, deprivation, and desperation can undermine ethical decision-making. The episode provides insights into how individuals and groups rationalize violations of principles they previously held absolute and how extreme circumstances can reveal the limits of moral commitment.

The supernatural consequences that follow the violation of divine law speak to contemporary concerns about actions that have irreversible environmental, social, or psychological consequences. While modern readers may not believe in literal divine retribution, the image of actions that fundamentally disrupt natural or social order resonates with understanding of how certain behaviors can trigger cascading consequences that are difficult or impossible to reverse.

Perhaps most significantly, Book 12's exploration of how external constraints can enable individuals to experience dangerous temptations safely—as in Odysseus's binding to the mast—offers insights into contemporary approaches to managing addiction, impulse control, and other situations where willpower alone may be insufficient. The episode suggests that wisdom lies not in eliminating temptation but in creating structural supports that prevent momentary weakness from leading to permanent disaster.

Study Questions

The Ethics of Sacrificial Leadership: Odysseus chooses to sail closer to Scylla, knowing this decision will cost six men their lives, rather than risk everyone to Charybdis. He makes this choice without consulting his crew about the trade-off. How do we evaluate this decision morally? When, if ever, are leaders justified in making unilateral choices about acceptable losses? What does this episode suggest about the relationship between effective leadership and moral burden?

Knowledge as Temptation and Burden: The Sirens offer Odysseus complete knowledge about the past and future, while Circe's warnings give him painful foreknowledge about inevitable losses ahead. How does Book 12 explore the relationship between knowledge and suffering? Is ignorance sometimes preferable to knowledge? How do we balance our desire for understanding with the psychological costs of knowing things we cannot change?

Divine Law versus Human Survival: The crew's violation of the prohibition against killing the sacred cattle reflects the conflict between absolute moral principles and extreme necessity. Their rationalization that they can make amends later if they survive suggests a pragmatic approach to divine commands. How should we understand the relationship between universal ethical principles and situational pressures? Are there moral laws that admit no exceptions, even in life-threatening circumstances?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 13. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled Ithaca at Last and spans pages 286-300. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled Two Tricksters and spans pages 316-331.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you've found value in my work and it has helped, informed, or entertained you, I'd be grateful if you'd consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue creating content and means more than you know. Even small contributions make a real difference and allow me to keep sharing my work with you. Thank you for reading and for any support you're able to offer.

Affiliate links: You can click on the title of any book mentioned in this article to purchase your own copy. These are affiliate links, earning me a very small commission for any purchase you make.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Book 12, as in the preceding books describing Odysseus's travels, explores themes of temptation, leadership choices, relationships with the divine and moral dilemmas that are universal throughout the history of the written word. In my mind, there is a straight line between the temptation of acquiring hidden knowledge from the Sirens and the Garden of Eden. Homer has Odysseus and his men avoid the damnation of the Sirens through mutual assistance. Odysseus plugs his men's ears and his men lash Odysseus to the mast and follow his commands not to release him even if ordered to do so. We avoid "damnation" only through overt acts of mutual aid.

The dilemma that Odysseus faces in sacrificing 6 of his men to save the rest is the most anguished and difficult imaginable. It is a stark reminder of the burdens of leadership. Few who aspire to it truly understand what is sometimes required. Ironically, the sacrifice of 6 men to get through the straits between Scylla and Charybdis turns out not to be such great sacrifice after all, considering what happens when the crew eats Helios's cattle.

The fact that only Odysseus survives the trials and tribulations of his travels is Homer's way of setting Odysseus apart. He has evolved into a person of uncommon courage, leadership and moral resolve, i.e., a true hero.