The Kingdom of the Dead

The Odyssey Book 11

Exploring Life through the Written Word

"By god, I'd rather slave on earth for another man—some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive—than rule down here over all the breathless dead."

Dear friends,

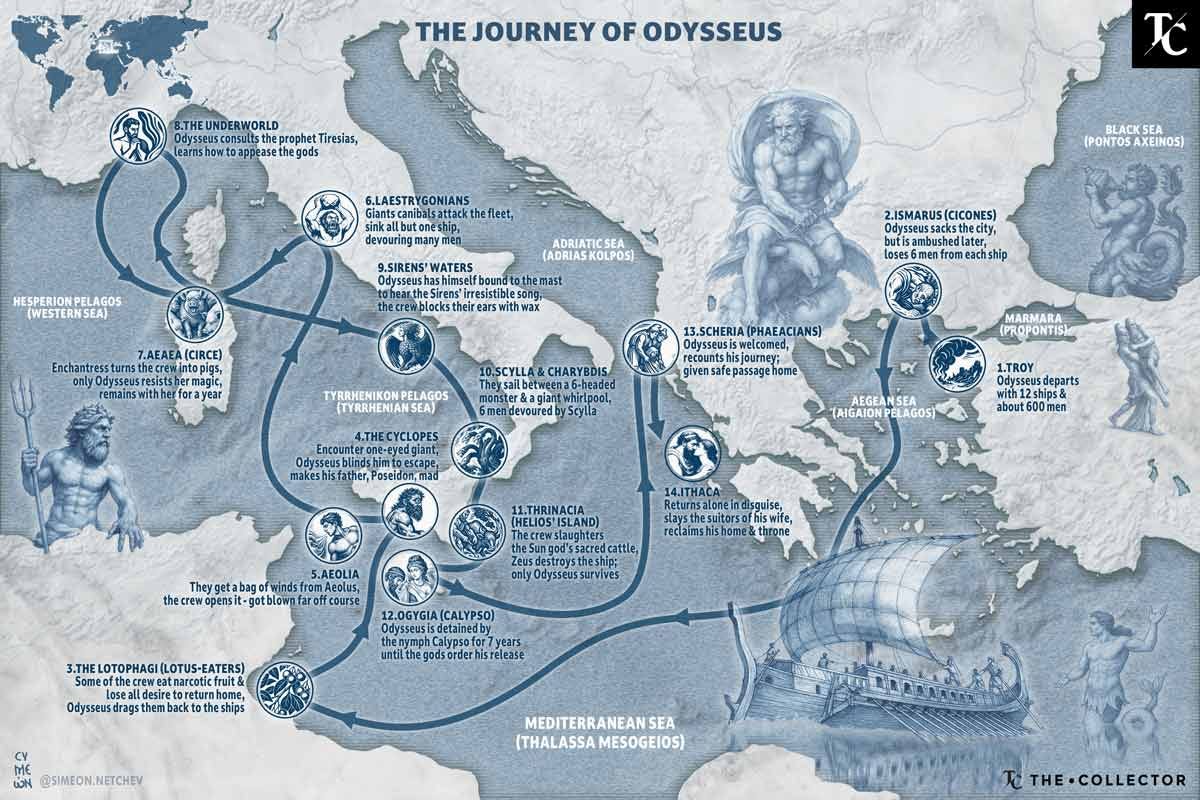

Book 11 of Homer's The Odyssey, known as the "Nekyia" or "Book of the Dead," represents one of the most haunting and psychologically complex episodes in all of ancient literature. This book transforms Odysseus from a wandering hero seeking his homeland into a spiritual pilgrim confronting the ultimate mysteries of death, memory, and human meaning. Following Circe's detailed instructions, Odysseus undertakes a journey to the edge of the world to consult the spirit of the blind prophet Tiresias, but what begins as a quest for practical guidance becomes a profound meditation on mortality, legacy, and the weight of the past.

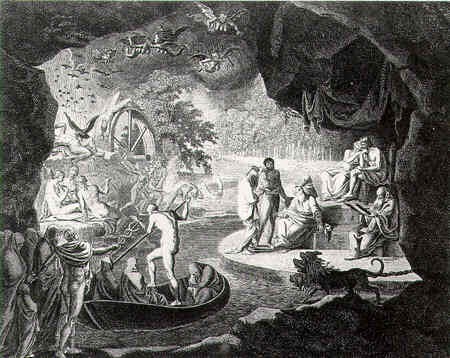

The book opens with Odysseus and his men sailing northward from Circe's island, following her precise directions to reach the entrance to the underworld. They travel beyond the familiar Mediterranean world into the mythical realm where the sun never shines, arriving at the confluence of two rivers—the Pyriphlegethon (River of Fire) and the Cocytus (River of Lamentation)—which flow into the Acheron, the boundary between the world of the living and the dead. Here, at the very edge of existence, Odysseus must perform the elaborate ritual that Circe has prescribed.

The ritual itself is both precise and deeply symbolic. Odysseus digs a cubit-square pit and pours libations of honey, milk, wine, and water, sprinkling the offerings with white barley. He then sacrifices a young ram and a black ewe, allowing their blood to flow into the pit while turning their heads toward Erebus, the realm of darkness. The blood serves as the crucial element that will allow the spirits of the dead to speak—without it, they remain mere shadows, unable to communicate with the living.

As soon as the blood flows, the shades of the dead begin to emerge from Erebus in overwhelming numbers. Warriors killed at Troy, women who died in childbirth, young men cut down in their prime, and ancient heroes all press forward, desperate to taste the blood that will temporarily restore their capacity for speech and memory. The scene becomes chaotic as hundreds of spirits surge toward the pit, creating a nightmarish vision of humanity's collective mortality.

Odysseus draws his sword and stands guard over the blood, following Circe's instructions to allow no spirit to drink until Tiresias has been consulted. However, the first shade to approach is not the prophet but Elpenor, one of Odysseus's own men who died accidentally on Circe's island just before their departure. Elpenor had fallen asleep on the palace roof after drinking, and when awakened by the commotion of departure, he forgot where he was and fell to his death. His spirit, unburied and unmourned, begs Odysseus to return to Circe's island and provide him with proper funeral rites, warning that his unquiet ghost could bring divine wrath upon the expedition.

The encounter with Elpenor establishes the fundamental tension that will define the entire episode: the obligations that the living owe to the dead and the power that the dead continue to exercise over the living. Odysseus promises to fulfill Elpenor's request, demonstrating the binding nature of duty that transcends even death itself.

When Tiresias finally appears, the blind prophet drinks the blood and immediately recognizes Odysseus, addressing him as "son of Laertes" and acknowledging the hero's desperate desire for homecoming. Tiresias reveals that Poseidon continues to harbor wrath against Odysseus for blinding the Cyclops Polyphemus, and this divine anger will continue to complicate his journey. However, the prophet offers hope: Odysseus can still reach Ithaca if he and his men exercise restraint when they reach the island of the Sun God, Helios.

Tiresias provides crucial warnings about the Cattle of the Sun, sacred animals that must not be harmed under any circumstances. If the cattle are killed, disaster will follow—Odysseus's ship and crew will be destroyed, and even if Odysseus himself survives, he will reach home alone, after many years, to find his house filled with suitors consuming his wealth and pursuing his wife. The prophet then offers an even more disturbing vision of Odysseus's ultimate fate: even after reclaiming his kingdom, he must undertake another journey, carrying an oar inland until he reaches people who know nothing of the sea, where he must make a final sacrifice to Poseidon to appease the god's wrath.

After Tiresias departs, Odysseus allows other spirits to approach the blood and speak. The most emotionally devastating encounter is with his mother, Anticleia, whose presence comes as a complete shock. When he left for Troy, she was alive and well, and her appearance among the dead forces him to confront the personal cost of his long absence from home. Anticleia explains that she died of grief, pining for her lost son, unable to bear the uncertainty about his fate.

The conversation with his mother becomes one of the most poignant moments in the entire epic. She provides news of his father Laertes, who has withdrawn from society and lives as a hermit, and of his wife Penelope, who remains faithful but is under increasing pressure from the suitors. When Odysseus attempts to embrace his mother's shade three times, she slips through his arms like a shadow or a dream, leading to his anguished cry about the nature of death and the impossibility of physical connection with the departed.

Following this personal revelation, Odysseus encounters a parade of legendary women from Greek myth and history. He meets the wives and daughters of heroes: Tyro, who bore children to Poseidon; Antiope, mother of the founders of Thebes; Alcmene, mother of Heracles; and many others whose stories form the foundation of Greek legendary tradition. Each woman's brief appearance serves to connect Odysseus's personal journey to the broader sweep of heroic history, establishing his adventure as part of the continuing narrative of divine-human interaction that shapes the world.

The most significant encounter among the heroic shades is with Agamemnon, Odysseus's former commander at Troy. Agamemnon's spirit reveals the shocking story of his murder by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus immediately upon his return from Troy. The great king, who led the Greek armies to victory over Troy, was struck down in his own palace while bathing, killed like "an ox at the manger." Agamemnon's bitter account serves as both warning and counterpoint to Odysseus's own situation—he too will return home to find his house occupied by men who covet his wife and wealth, but Agamemnon's fate demonstrates what happens when a homecoming hero is not prepared for domestic treachery.

Agamemnon's spirit offers crucial advice about how Odysseus should handle his own return, counseling him to arrive in secret rather than openly, since wives cannot be trusted. However, he also acknowledges that Penelope is different from Clytemnestra—more faithful and virtuous—suggesting that Odysseus's homecoming might follow a different pattern. This conversation establishes the parallel between the two heroes while highlighting the crucial differences in their situations and their wives' characters.

The encounter with Achilles provides the most philosophically complex moment in the entire book. The greatest warrior of the Trojan War appears among the dead, and Odysseus attempts to console him by praising his legendary status and suggesting that death has not diminished his honor. Achilles' response shatters conventional heroic values: he declares that he would rather be a landless peasant among the living than rule over all the dead. This statement represents a fundamental challenge to the heroic code that values glory and posthumous fame above life itself, suggesting that existence itself is more valuable than any honor that death might bring.

Despite this declaration of life's supreme value, Achilles still hungers for news of his son Neoptolemus and his father Peleus, demonstrating that even in death, family connections retain their power. When Odysseus reports that Neoptolemus has proven himself a worthy warrior, Achilles' spirit brightens with pride, showing that parental love transcends even the boundaries of death.

The encounter with Ajax the Great proves more troubling, as the hero's shade refuses to speak to Odysseus, still nursing anger over their competition for Achilles' armor after that hero's death. Ajax's suicide following his defeat in that contest created a wound that not even death has healed, and his refusal to acknowledge Odysseus's attempts at reconciliation demonstrates the enduring power of resentment and wounded pride.

As the episode continues, Odysseus observes the punishments of famous sinners: Minos judging the dead, Orion hunting eternal prey, and the eternal torments of Tantalus and Sisyphus. These glimpses of divine justice in action provide a framework for understanding the moral order that governs both the living and the dead. The sinners' punishments—Tantalus forever reaching for food and water that disappears at his touch, Sisyphus eternally pushing his boulder up the mountain—represent the consequences of hubris and crimes against the gods.

The book concludes with Odysseus's desire to remain longer and speak with more heroes, but the increasing agitation of the dead and his own fear of attracting unwanted attention from Persephone forces him to retreat. He and his men flee back to their ship and sail away from the entrance to the underworld, carrying with them the knowledge and warnings they have gained from their consultation with the dead.

Literary Analysis

Book 11 of The Odyssey functions as the spiritual and psychological center of The Odyssey, transforming what began as an adventure narrative into a deep meditation on mortality, memory, and meaning. The "Nekyia" represents one of literature's earliest and most influential attempts to map the geography of death and to explore the relationship between the living and the dead. Homer's vision of the underworld is not simply a supernatural adventure but a complex psychological landscape where the hero must confront his own mortality and the weight of his past actions.

The ritual that Odysseus performs to summon the dead operates on multiple symbolic levels. The blood sacrifice that enables communication with the spirits reflects ancient Greek beliefs about the nature of death and consciousness—the dead retain their memories and personalities but require the life force contained in blood to interact with the world of the living. This detail transforms the underworld from a realm of punishment or reward into a kind of liminal space where the boundaries between life and death become permeable under the right circumstances.

The physical description of the underworld's entrance—at the confluence of rivers whose names evoke fire and lamentation—creates a geography that is both mythical and psychologically resonant. The location beyond the reach of the sun suggests a realm outside normal time and space, while the flowing waters represent the irreversible passage from life to death. The pit that Odysseus digs becomes a kind of altar or communication device, creating a temporary bridge between worlds that exists only as long as the ritual is maintained.

The overwhelming rush of spirits toward the blood creates one of the most powerful images in ancient literature—the collective hunger of the dead for contact with life. This scene suggests that death involves not the cessation of consciousness but rather its isolation from meaningful interaction, creating a kind of eternal loneliness that can only be temporarily relieved through ritual contact with the living. The image speaks to fundamental human anxieties about death as separation and isolation rather than simply as ending.

Homer's presentation of the various categories of dead—heroes, ordinary people, sinners, and judges—creates a complex moral and social hierarchy that reflects the values and concerns of ancient Greek society while addressing universal questions about justice and meaning after death. The presence of figures like Minos as judge and the elaborate punishments of sinners like Tantalus and Sisyphus establish the underworld as a realm where divine justice operates according to recognizable moral principles, providing a framework for understanding the consequences of human actions that extends beyond mortal life.

Personal Revelation and Heroic Identity

The encounter with Anticleia represents the emotional climax of the book and one of the most psychologically penetrating moments in all of ancient literature. Odysseus's shock at discovering his mother among the dead forces him to confront the personal cost of his heroic adventures. The revelation that she died of grief over his absence transforms his quest from a matter of personal desire for homecoming into a moral obligation—his prolonged absence has already claimed an innocent victim, and his continued wandering only increases the suffering of those who love him.

The detail that Anticleia died not from illness or accident but from emotional anguish over her son's fate speaks to Homer's sophisticated understanding of the connection between psychological and physical well-being. Her death represents the kind of collateral damage that heroic adventures inflict on the families left behind, forcing readers to consider the hidden costs of glory and adventure. The scene anticipates modern understanding of how separation and uncertainty can have lethal psychological and physical effects on those who wait for absent loved ones.

The three failed attempts to embrace his mother's shade create one of the most haunting images in the epic, as physical affection—one of the most basic forms of human connection—proves impossible across the boundary of death. Odysseus's frustration and anguish at his inability to comfort his mother or receive comfort from her speaks to fundamental human needs for physical connection and the devastating isolation that death imposes. The comparison of his mother's shade to a shadow or dream emphasizes the insubstantial nature of the dead while highlighting the intensity of Odysseus's desire for connection.

The conversation with Agamemnon functions as a dark mirror to Odysseus's own situation, providing both warning and context for his eventual homecoming. Agamemnon's murder by his wife and her lover represents the ultimate betrayal—the violation of the most fundamental bonds of marriage, hospitality, and kinship. The detail that he was killed "like an ox at the manger" emphasizes the degrading nature of his death, reducing the great king to the level of a sacrificial animal.

However, Agamemnon's acknowledgment of Penelope's virtue provides crucial contrast and hope. His advice to return home in secret rather than openly reflects hard-won wisdom about the dangers that await returning heroes, but his praise for Penelope suggests that not all wives are treacherous and that Odysseus's homecoming might follow a different pattern. This conversation establishes the framework for understanding the suitors' threat while also affirming the possibility of successful reunion based on mutual fidelity and love.

The Challenge to Heroic Values

The encounter with Achilles represents perhaps the most philosophically radical moment in the entire Odyssey, as the greatest warrior of the heroic age explicitly rejects the value system that made him famous. Achilles' declaration that he would rather be a living peasant than ruler of the dead strikes at the heart of the heroic code that values glory and posthumous fame above life itself. This moment represents a fundamental critique of the warrior values that dominate much of ancient literature, suggesting that existence itself is more valuable than any honor that might survive death.

The statement is particularly powerful coming from Achilles, who in life chose a short, glorious existence over a long, obscure one. His perspective from beyond death provides a devastating critique of that choice, suggesting that the heroic code's emphasis on glory and honor represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes life valuable. The scene anticipates later philosophical developments in Greek thought that would increasingly emphasize the intrinsic value of life and consciousness over external measures of success or honor.

Yet even as Achilles rejects the heroic code, his immediate concern for his son and father demonstrates that some human values transcend even death. His joy at learning of Neoptolemus's prowess in battle and his anxiety about his father's welfare show that parental love and filial obligation remain powerful even in the realm of the dead. This detail complicates his rejection of heroic values by showing that he still cares about the achievements and well-being of his loved ones, suggesting that the critique applies to personal glory-seeking rather than to all forms of excellence and achievement.

The refusal of Ajax to speak to Odysseus provides another perspective on heroic pride and the enduring power of resentment. Ajax's suicide following his defeat in the competition for Achilles' armor represents one of the most tragic examples of heroic pride leading to self-destruction. His continued anger in death suggests that some wounds cannot be healed by time or even by the ultimate perspective that death provides, creating a vision of eternal resentment that is both psychologically realistic and morally troubling.

Historical Context and Religious Beliefs

Book 11 reflects and shapes ancient Greek beliefs about death, the afterlife, and the relationship between the living and the dead in ways that would influence Western thought for millennia. The vision of the underworld presented here differs significantly from later Christian concepts of heaven and hell, creating instead a realm where the dead continue to exist in a diminished state, retaining their memories and personalities but lacking the vitality and agency that characterize living existence.

The ritual elements of the nekyia—the specific sacrifices, libations, and procedures that Odysseus follows—reflect actual ancient Greek religious practices related to death and communication with the dead. Archaeological evidence suggests that similar rituals were practiced at various sites throughout the Greek world, particularly at places associated with oracles and divine communication. The detailed description of the ritual in Homer may have served as a kind of religious instruction for readers, providing a template for understanding how proper relationships with the dead should be maintained.

The concept of proper burial and funeral rites, emphasized in Elpenor's plea for attention to his unburied body, reflects central concerns of ancient Greek religious and social practice. The belief that the unburied dead could not find rest and might bring misfortune to the living created powerful obligations for families and communities to ensure that the dead received appropriate ritual attention. Elpenor's condition—having died accidentally and been left unburied in the rush to depart Circe's island—represents a violation of these fundamental obligations that must be corrected to maintain proper relationships between the living and the dead.

The presence of divine judges like Minos and the eternal punishments of sinners like Tantalus and Sisyphus reflect Greek beliefs about divine justice and moral order. These figures represent the idea that the gods maintain a moral framework that extends beyond mortal life, ensuring that crimes and violations of divine law receive appropriate punishment. The specific nature of the punishments—Tantalus's eternal hunger and thirst, Sisyphus's endless labor—reflects the Greek concept of fitting retribution, where the punishment mirrors and extends the nature of the original offense.

The parade of legendary women that Odysseus encounters serves to connect his personal story to the broader sweep of Greek mythological tradition. These figures—Tyro, Antiope, Alcmene, and others—represent the founding mothers of heroic lineages and city-states, establishing Odysseus's journey as part of the continuing narrative of divine-human interaction that shapes Greek cultural identity. The episode demonstrates how individual stories gain meaning through their connection to larger patterns of myth and history.

Contemporary Relevance and Psychological Insights

The psychological dynamics explored in Book 11 continue to resonate with contemporary understanding of grief, trauma, and the human need to maintain connections with the deceased. Odysseus's encounter with his mother speaks to universal experiences of loss and the particular anguish of learning about a loved one's death after the fact. The detail that Anticleia died of grief over her son's absence reflects contemporary understanding of how prolonged uncertainty and separation can have severe psychological and physical health consequences.

The failed attempts to embrace his mother's shade speak to modern psychological insights about the physical dimensions of grief and the importance of touch in human comfort and connection. The image of the deceased as present but untouchable captures the essential paradox of mourning—the continued psychological presence of the dead combined with their physical absence. This dynamic appears repeatedly in contemporary literature and psychology as people struggle to maintain relationships with deceased loved ones while accepting the finality of death.

The encounter with Achilles offers insights into how perspectives on success, achievement, and meaning can change radically based on experience and reflection. Achilles' rejection of his earlier values reflects contemporary understanding of how proximity to death can cause fundamental reassessment of priorities and values. His statement about preferring humble life to glorious death anticipates modern psychological research showing that people facing mortality often shift their focus from external achievements to relationships and immediate experience.

The vision of the underworld as a place where consciousness continues but agency and vitality are diminished speaks to contemporary anxieties about aging, dementia, and other conditions that affect mental capacity while leaving awareness intact. The image of the dead as shadows of their former selves, dependent on external assistance (the blood sacrifice) to achieve full consciousness and communication, resonates with modern medical and psychological understanding of various states of diminished capacity.

The theme of unfinished business between the living and the dead, exemplified in the encounters with Elpenor, Agamemnon, and Ajax, reflects contemporary therapeutic understanding of how unresolved conflicts and obligations can continue to affect both individuals and families long after death has occurred. The book's exploration of how the dead continue to make claims on the living speaks to modern psychology's recognition of the ongoing influence of deceased family members and the importance of working through grief and guilt to achieve psychological health.

The ritual framework that enables communication with the dead can be understood as an early example of what contemporary psychology might recognize as a therapeutic or ceremonial space where individuals can confront their relationships with loss, trauma, and mortality. The specific procedures that Odysseus follows create a bounded, sacred context where normally impossible conversations can take place, similar to therapeutic or spiritual practices that help people process grief and maintain healthy relationships with memory and loss.

The book's exploration of how knowledge of death affects the living—from Tiresias's prophecies about future suffering to the revelations about family members' fates—speaks to contemporary concerns about how much people should know about future difficulties or losses. The tension between the value of foreknowledge and the burden it imposes reflects ongoing debates in medical ethics, genetic counseling, and other fields where advance knowledge of future problems must be balanced against psychological well-being.

Perhaps most significantly, Book 11's meditation on the relationship between life and death, consciousness and meaning, continues to speak to fundamental philosophical questions that remain central to human experience. The book's exploration of what survives death—memory, personality, relationships, obligations—and what is lost—agency, physical presence, the capacity for new experience—provides a framework for thinking about mortality that remains psychologically and philosophically relevant.

The episode's emphasis on the ongoing obligations between the living and the dead speaks to contemporary understanding of how families and communities maintain connections across generations through ritual, memory, and storytelling. The book demonstrates how the dead continue to influence the living through the stories told about them and the obligations they leave behind, anticipating modern psychological and sociological insights about intergenerational transmission of values, trauma, and identity.

Study Questions

The Nature of Heroic Values: Achilles' declaration that he would rather be a living peasant than rule over the dead represents a fundamental challenge to traditional heroic values that prioritize glory and posthumous fame. How does this statement change our understanding of heroic achievement throughout the epic? What does the contrast between Achilles' perspective and his continued concern for his son's reputation suggest about which human values transcend death?

Obligations Between Living and Dead: The encounters with Elpenor, Anticleia, and Agamemnon all involve different types of obligations and claims that the dead make upon the living. How does Book 11 explore the nature of these continuing relationships? What does the text suggest about how the living should balance their obligations to the dead with their responsibilities to their own lives and futures?

Knowledge and Burden: Tiresias provides Odysseus with crucial information about his future, including warnings about dangers ahead and prophecies about his ultimate fate. However, this knowledge comes with psychological costs—awareness of future suffering and the burden of trying to prevent predicted disasters. How does the book explore the relationship between knowledge and suffering? Is Odysseus better or worse off for having consulted the dead?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 12. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled The Cattle of the Sun and spans pages 271-285. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled Difficult Choices and spans pages 301-315.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you've found value in my work and it has helped, informed, or entertained you, I'd be grateful if you'd consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue creating content and means more than you know. Even small contributions make a real difference and allow me to keep sharing my work with you. Thank you for reading and for any support you're able to offer.

Affiliate links: You can click on the title of any book mentioned in this article to purchase your own copy. These are affiliate links, earning me a very small commission for any purchase you make.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Just brilliant, Matthew. You rival any classicist in your explication

The Achilles passage never fails to hit hard.