Exploring Life through the Written Word

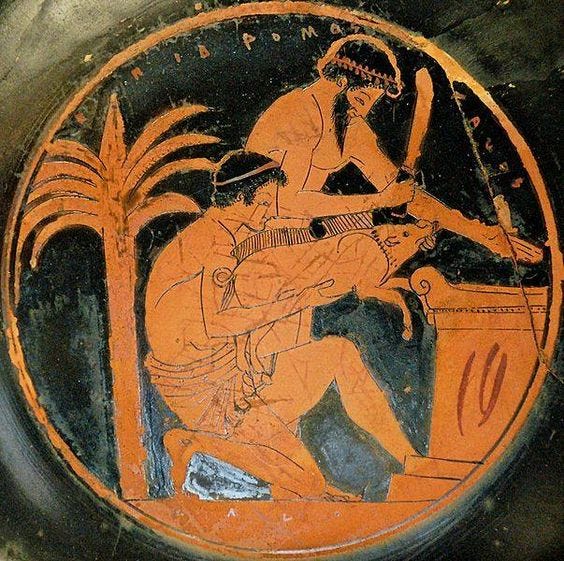

"I tell you, friend—and know I speak the truth—/ I never heard such praise of any man/ as when my queen asks news of her poor lord/ from any wanderer come to our land."

Dear friends,

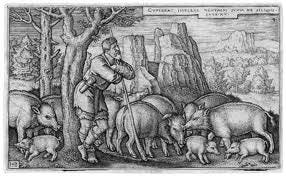

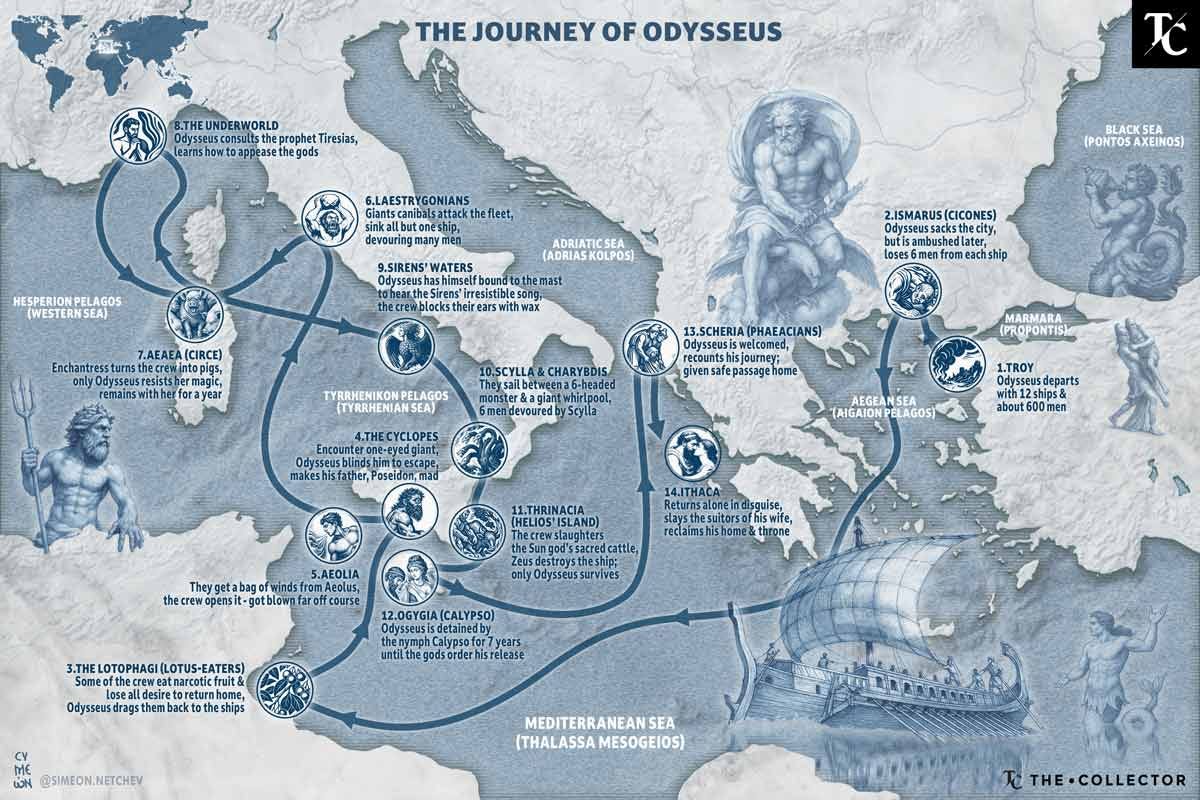

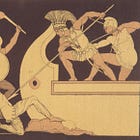

Book 14 of Homer's The Odyssey marks the moment Odysseus finally sets foot on Ithaca after twenty years of absence. Here we see the sacred bonds of hospitality (xenia), the virtue of loyalty, and the complex relationship between appearance and reality. Through Odysseus's encounter with Eumaeus, his faithful swineherd, Homer crafts a narrative that is intimate and universal, grounding the epic's mythic scope in human moments of recognition, deception, and devotion.

The chapter's significance extends far beyond its immediate plot function. While Odysseus has finally reached his homeland, he must navigate the treacherous political landscape that has developed in his absence. The Ithaca he returns to is not the kingdom he left; it is a realm under siege, where suitors consume his wealth, threaten his family, and challenge the very foundations of his authority. In this context, Book 14 becomes a masterclass in strategic thinking, as Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, gathers crucial intelligence while testing the loyalty of those who once served him. The chapter demonstrates Homer's sophisticated understanding of narrative tension, character development, and the psychological complexities of homecoming.

The book opens with Odysseus, still disguised by Athena as an aged beggar, making his way from the harbor where the Phaeacians left him toward the interior of Ithaca. His destination is not the palace, where logic might dictate a returning king should go, but rather the humble dwelling of Eumaeus, his swineherd. This choice reveals Odysseus's strategic acumen; he understands that knowledge and careful preparation must precede action, especially in a situation fraught with political danger.

The encounter between Odysseus and Eumaeus unfolds with exquisite dramatic irony. Eumaeus, unaware of his master's true identity, embodies the very essence of loyal service and proper hospitality. Despite his modest circumstances, he welcomes the apparent stranger with warmth and generosity, immediately offering food, drink, and shelter. The swineherd's dogs, initially hostile to the stranger, are quickly calmed by their master's intervention—a detail that subtly foreshadows the larger theme of recognition that will dominate later books.

As the two men share a meal, their conversation reveals the depth of Ithaca's troubles. Eumaeus speaks with heartfelt grief about his absent master, lamenting Odysseus's presumed death and the chaos that has befallen the household in his absence. He describes the suitors' wasteful consumption of the estate's resources, their disrespectful treatment of Penelope and Telemachus, and the general breakdown of social order. Throughout this recitation, Odysseus maintains his disguise while internally processing the intelligence he gathers about his enemies and allies.

The narrative tension intensifies as Eumaeus expresses his unwavering loyalty to his absent master, even going so far as to declare his skepticism about any claims of Odysseus's return. This ironic situation—a man professing disbelief in his master's return while unknowingly entertaining that very master—exemplifies Homer's mastery of dramatic irony. The swineherd's doubt serves a crucial narrative function, highlighting the extraordinary nature of Odysseus's survival and return while emphasizing the loyalty that persists despite apparent hopelessness.

Odysseus, still maintaining his beggar persona, crafts an elaborate false tale about his identity and origins. He claims to be a Cretan who has experienced military service, slavery, and various adventures throughout the Mediterranean. This fabricated autobiography serves multiple purposes: it allows Odysseus to remain anonymous while gathering information, provides a plausible explanation for his knowledge of distant lands and events, and creates opportunities to probe Eumaeus's reactions and loyalties.

The conversation between the two men extends through the day and into the evening, creating an atmosphere of intimacy and mutual respect despite the deception at its heart. Eumaeus proves to be not only loyal but also wise, offering philosophical reflections on fate, divine justice, and the nature of suffering. His dignity in poverty and his unwavering moral principles stand in stark contrast to the suitors' behavior, establishing him as a moral touchstone within the narrative.

As night falls, the practical concerns of shelter and warmth become paramount. Eumaeus insists on providing his guest with adequate clothing and bedding, even offering his own cloak. This gesture prompts Odysseus to tell yet another fabricated story—this time about a night during the Trojan War when he cunningly obtained a cloak through deception. The tale serves as both entertainment and a subtle test of his host's generosity, which Eumaeus passes admirably by immediately offering his own cloak to ensure his guest's comfort.

The book concludes with both men settling in for the night, but significantly, Eumaeus chooses to sleep outside with his swine rather than in the comfort of his hut. This detail emphasizes his dedication to his duties and his selfless nature. Meanwhile, Odysseus lies inside, protected by his loyal servant's hospitality, gathering his strength and planning his next moves in the complex game of reclaiming his kingdom.

Literary Analysis

The Architecture of Dramatic Irony

Homer's employment of dramatic irony in Book 14 of The Odyssey represents one of the most sophisticated examples of this literary device in ancient literature. The audience knows Odysseus's true identity while Eumaeus remains oblivious, creating a multi-layered reading experience that operates simultaneously on levels of surface narrative and deeper meaning. This ironic structure serves several crucial functions within the larger epic framework.

First, it allows Homer to explore the theme of recognition—one of the epic's central concerns—in a gradual, psychologically realistic manner. Rather than providing the immediate gratification of reunion, the poet extends the moment of anticipation, building tension while revealing character through extended interaction. The delay serves to heighten both the emotional impact of eventual recognition and the audience's appreciation of the relationships that have endured despite separation and hardship.

Second, the dramatic irony facilitates character development for both protagonists. Odysseus demonstrates his strategic thinking and emotional control, maintaining his disguise despite what must be powerful urges to reveal himself to this loyal friend. His ability to craft convincing lies while gathering crucial intelligence showcases the cunning intelligence (metis) that defines his character throughout the epic. Meanwhile, Eumaeus reveals himself to be far more than a simple servant; his philosophical reflections, moral integrity, and dignified bearing establish him as one of the epic's most admirable figures.

The Sacred Bond of Xenia

The concept of xenia—ritualized hospitality between host and guest—permeates Book 14 as both a social institution and a moral measuring stick. Eumaeus's immediate and generous welcome of the disguised Odysseus exemplifies ideal hospitality, demonstrating how proper xenia transcends social class and economic circumstances. Despite his modest means, the swineherd offers the best he has: food from his own table, wine from his stores, and warmth from his fire.

This hospitality stands in stark contrast to the suitors' behavior, which represents a perversion of xenia. Where guests should be welcomed and protected, the suitors have become parasitic invaders, consuming their host's resources without reciprocal obligation or respect. Their violation of hospitality customs marks them as fundamentally lawless, deserving of the divine retribution that awaits them.

Homer's treatment of xenia in this chapter also reveals its function as a civilizing force. The ritualized exchange of hospitality creates bonds between strangers, establishes mutual obligations, and maintains social order even in the absence of formal political structures. Eumaeus's adherence to these customs, even when hosting an apparent beggar, demonstrates the moral foundation that will ultimately enable Odysseus's restoration to power.

Class, Loyalty, and Social Order

Homer presents a nuanced exploration of social hierarchy and the bonds that transcend class distinctions. Eumaeus occupies a complex position within Ithaca's social structure—he is technically a slave, yet he possesses dignity, wisdom, and moral authority that surpass many of his social superiors. His backstory, revealed in fragments throughout the chapter, tells of royal birth and subsequent enslavement, creating a character who embodies both high and low social stations.

The relationship between Odysseus and Eumaeus transcends the typical master-servant dynamic, approaching something closer to friendship or kinship. This relationship model provides an alternative to the hierarchical structures that dominate the palace, where relationships are defined by power, competition, and exploitation. The mutual respect between the king and the swineherd suggests a vision of social order based on merit, loyalty, and shared values rather than birth or wealth alone.

Homer uses this relationship to critique the corruption that has infected Ithaca's ruling class. While the noble-born suitors demonstrate greed, violence, and disrespect, the slave-born Eumaeus embodies honor, generosity, and wisdom. This inversion of expected moral hierarchies serves both as social commentary and as preparation for the epic's resolution, where justice will be restored not through conventional political means but through the actions of those who have maintained their integrity regardless of their social position.

The Art of Deception and Truth

The elaborate lies that Odysseus tells Eumaeus serve multiple narrative and thematic functions. On the surface level, they provide necessary camouflage for his intelligence-gathering mission. However, they also engage with deeper questions about the relationship between truth and fiction, reality and appearance, that pervade the entire epic.

Odysseus's fabricated stories contain elements of truth mixed with invention, creating what might be called "true lies"—narratives that, while factually false, reveal deeper truths about human experience, suffering, and resilience. His claimed identity as a Cretan warrior who has experienced military service, enslavement, and wandering parallels his own experiences in ways that make the deception emotionally authentic even while remaining literally false.

This complex relationship between truth and falsehood reflects broader themes in The Odyssey about identity, recognition, and the stories we tell about ourselves. Odysseus's ability to craft convincing narratives demonstrates not just his cunning but his deep understanding of human psychology and social dynamics. His lies work because they tap into universal experiences of loss, struggle, and survival that resonate with his audience regardless of their literal accuracy.

Historical and Cultural Connections

Book 14 provides valuable insights into the social, economic, and political structures of the ancient Greek world. The detailed descriptions of Eumaeus's household management, animal husbandry practices, and daily routines offer a window into the agricultural foundations of Homeric society. The swineherd's operation represents the kind of specialized labor that supported the palatial economies of the late Bronze Age, with careful attention to breeding, feeding, and protecting valuable livestock.

The chapter also illuminates the institution of slavery in the ancient world, presenting a more complex picture than often appears in historical generalizations. Eumaeus's status as a slave does not diminish his dignity or agency; he manages significant resources, makes independent decisions, and commands respect from both superiors and subordinates. His story suggests that slavery in the Homeric world, while undoubtedly harsh and unjust, could encompass a range of experiences and relationships that defy simple categorization.

The political situation described in Book 14—a kingdom without a king, nobles competing for power, and the breakdown of traditional authority structures—reflects historical patterns that recurred throughout the ancient Mediterranean world. The suitors' behavior mirrors the actions of aristocratic factions in many Greek city-states, where competition for political dominance often led to civil conflict and social disorder.

Contemporary Relevance

The themes explored maintain remarkable relevance for contemporary readers, speaking to enduring human concerns that transcend historical periods and cultural boundaries. The question of loyalty in the absence of immediate reward or recognition resonates in a modern world where personal and professional relationships often seem increasingly transactional. Eumaeus's unwavering commitment to his absent master, maintained without hope of recognition or reward, offers a model of integrity that challenges contemporary assumptions about motivation and behavior.

The chapter's exploration of hospitality and social obligation speaks directly to current debates about immigration, refugee assistance, and community responsibility. Eumaeus's immediate welcome of a stranger, despite his own modest circumstances, provides a compelling example of how individuals can maintain humanitarian values regardless of their personal resources or social position. His actions suggest that true hospitality stems from character rather than capacity, offering lessons for contemporary discussions about social responsibility and mutual aid.

The theme of homecoming takes on particular significance in an era marked by global mobility, military deployments, and refugee displacement. Odysseus's discovery that home has changed in his absence, that familiar relationships must be rebuilt and trust reestablished, speaks to the experiences of millions of people who have experienced displacement, military service, or extended separation from family and community. The chapter's emphasis on the gradual, careful process of reconnection offers insights into the psychological and social challenges of reintegration.

The relationship between appearance and reality explored through Odysseus's disguise resonates in an age of social media, personal branding, and carefully curated public identities. The gap between how we present ourselves and who we truly are, the strategic deployment of persona for specific purposes, and the challenge of authentic recognition in environments of performative identity all find precedent in Odysseus's encounter with Eumaeus.

Perhaps most significantly, the chapter's portrayal of leadership in crisis speaks to contemporary challenges facing political and social institutions. Odysseus's careful information-gathering, strategic patience, and attention to the loyalty and capabilities of potential allies offer insights into effective leadership during periods of institutional breakdown. His recognition that restoration requires more than simply asserting authority—that it demands understanding, preparation, and the cultivation of relationships—provides lessons relevant to anyone facing the challenge of rebuilding damaged organizations or communities.

Conclusion

Book 14 of The Odyssey is a masterpiece of character development, thematic exploration, and narrative craft. Through the seemingly simple encounter between a disguised king and a loyal servant, Homer weaves together themes of identity, loyalty, hospitality, and social order that resonate throughout the epic and continue to speak to contemporary readers. The chapter's emphasis on the gradual, careful process of homecoming challenges simple notions of return and restoration, suggesting that true reconciliation requires patience, wisdom, and the rebuilding of fundamental relationships.

Eumaeus emerges as one of the epic's most compelling characters, embodying virtues that transcend social class and historical period. His unwavering loyalty, generous hospitality, and philosophical wisdom provide both a moral anchor for the narrative and a model of human excellence that remains relevant across cultural and temporal boundaries. The relationship between Odysseus and Eumaeus offers a vision of human connection based on mutual respect, shared values, and recognition of dignity that exists independent of social hierarchies.

The chapter's sophisticated use of dramatic irony, detailed character development, and thematic complexity demonstrate Homer's mastery of epic poetry and his deep understanding of human psychology. The work continues to reward careful reading and analysis, offering new insights into both the ancient world and enduring aspects of human experience. As Odysseus prepares for the next phase of his homecoming, readers are reminded that the greatest journeys are often those that lead us not just to new places, but to deeper understanding of ourselves and others.

Study Questions

The Nature of True Loyalty: Eumaeus maintains his devotion to Odysseus despite twenty years of absence and no concrete hope of his master's return. What does this suggest about the nature of loyalty? How does Eumaeus's faithfulness compare to other expressions of loyalty in the epic (Penelope's fidelity, Argos's recognition, the loyal servants versus the disloyal ones)? What are the costs and benefits of such unwavering commitment, and how might this apply to contemporary relationships and institutions?

Hospitality as Moral Measure: The contrast between Eumaeus's generous welcome of the disguised Odysseus and the suitors' abuse of hospitality at the palace serves as a key moral distinction in the epic. How does Homer use the ancient Greek concept of xenia (ritualized hospitality) to establish moral hierarchies among characters? What does this suggest about the relationship between social class and moral worth? How might the principles underlying xenia be relevant to contemporary discussions about social responsibility, immigration, and community support?

The Ethics of Deception: Odysseus maintains an elaborate deception throughout his encounter with Eumaeus, crafting detailed false stories about his identity and origins. Yet readers generally view this deception sympathetically, even admiringly. What makes Odysseus's lies acceptable or even praiseworthy in this context? How do we distinguish between harmful deception and strategic concealment? What does this suggest about the relationship between truth-telling and moral behavior, and how might these principles apply to contemporary situations involving privacy, security, or social navigation?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 15. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled The Prince Sets Sail for Home and spans pages 319-337. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled The Prince Returns and spans pages 350-368.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you've found value in my work and it has helped, informed, or entertained you, I'd be grateful if you'd consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue creating content and means more than you know. Even small contributions make a real difference and allow me to keep sharing my work with you. Thank you for reading and for any support you're able to offer.

Affiliate links: You can click on the title of any book mentioned in this article to purchase your own copy. These are affiliate links, earning me a very small commission for any purchase you make.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I do not have much to say about Book 14, it is not my favorite. I found myself bothered by the elaborate creation of a story. Yes, I understand its purpose and intention as a Homer storytelling technique, it just doesn't sit well with me. But maybe that is one of the things that makes The Odyssey such a timeless classic because it fits into the present, as it did in its creation.

Herein is the blurred line between truth and fiction - crafting convincing lies, you mention. How the storytelling theme (also mentioned in your analysis) of truth and leadership in crisis. We know Odysseus will fess his falseness, his begger status, his covert efforts to gain knowledge, and root out the fiction. That is a consolation, the story within the story, but I am again reminded how easy it is to tell a story about ourselves and believe its truth.

What I really appreciate more as The Odyssey continues is zenia as a social function. I believe "obligation" is a terse word as is "'expectation." Instead, (I might be feeling a bit touchy-feely today), zenia is an act of kindness. If I refer to your most recent posting about kindness as a reference. To be kind is simply an opportunity to extend roots. It is a moment of pause, the foundation for relationship building. In the current day it might be offering a cup of coffee or tea when someone unexpectedly shows up at the door. Sharing a bowl of soup from the crock pot or keeping muffins and cookies in the freezer that can be quickly thawed. Maybe it is something as simple as a glass of water.

Maybe kindness is again sitting around the table. I mean, there is a lot of feasting in The Odyssey so it can't be a terrible strategy for community building.

I loved how you brought Eumaeus’s quiet dignity to the forefront so well. Another ace piece.