The Steinbeck Review #4 - Head West Young Man

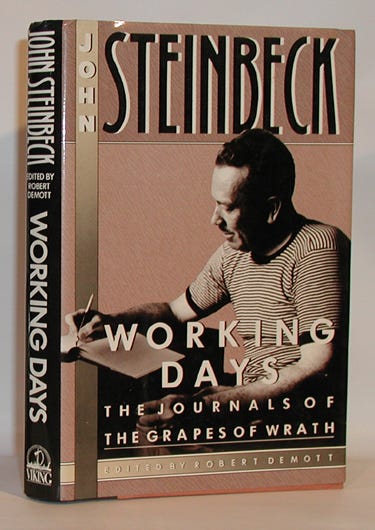

The Long Valley | Working Days | The Grapes of Wrath

Welcome to Beyond the Bookshelf, a community of readers and writers exploring the connections between life, literature, and stories - wherever we find them. My name is Matthew and I will be your guide on this adventure through the stories of our lives.

“In writing, habit seems to be a much stronger force than either willpower or inspiration.” - John Steinbeck

If you have recently joined us, previous installments of this series can be found here:

Steinbeck’s name was well known in American literary circles at that time, and his popularity only continued to grow as he released a new book every year or two. In the late 1930s, he was hired to write a series of articles for the San Francisco News, which came to be known as The Harvest Gypsies. Working from that source material and others, he would sit down in 1939 to write the book that cemented his legacy and raised him to canonical status. It would also change him forever, as a person and a writer.

“This thing fills me with pleasure. I don't know why, I can see it in the smallest detail.” - Narrator, “Breakfast”

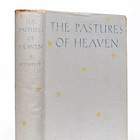

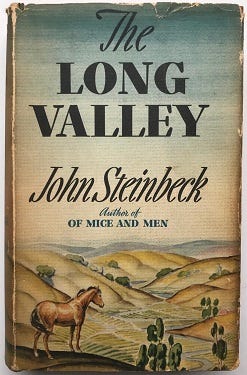

In 1938, Steinbeck wrote a second volume of short stories, which Viking Press published. The Long Valley provides a sampling of Steinbeck’s writing, as the 12 stories are not connected. Unlike much of his other writing, these appear to be experiments in which Steinbeck worked through his creative processes.

Most of the stories appeared in magazines or newspapers during Steinbeck’s formative years before they were collected and published together. All except one are set in the Salinas Valley and contain some of the darkest characters that Steinbeck would write about. The collection includes some surprising plot twists, atypical of his writing, including tales of abuse, revenge, and murder. His use of stark imagery to inform us about the human condition amplifies the dominant themes of loneliness, emotional isolation, repressed sexuality, and unfulfilling marital relationships.

Focusing on the universal experiences of ordinary individuals with particular attention to how they feel marginalized, even in places where they ostensibly belong, this short collection surveys the themes and styles Steinbeck evolved through and returned to throughout the early and middle stages of his career.

“This is the longest diary I ever kept. Not a diary of course but an attempt to map the actual working days and hours of a novel.” - John Steinbeck

Working Days is the journal Steinbeck kept while he wrote The Grapes of Wrath. It was never his intention to keep a detailed diary but rather to write daily his thoughts and feelings about the process of writing what he felt was his most important work. The journal provides all the emotional stages Steinbeck went through while writing and highlights his dogged determination to write the best book he could. He suffered from excruciating self-doubt and desperation at times but pushed on, seeking solitude and an environment free from distractions so he could better focus on the work.

“I’m not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people.”

Begun with confidence and hope, the journal progresses through all the stages of Steinbeck’s thinking as the days and months of writing roll by. His truth is on every page. The result was his masterpiece, but it cost Steinbeck much. His mental state became increasingly fragile as the work progressed, and his self-doubt consumed him.

“...and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

“To the red country and part of the gray country of Oklahoma, the last rains came gently, and they did not cut the scarred earth. The plows crossed and recrossed the rivulet marks. The last rains lifted the corn quickly and scattered weed colonies and grass along the sides of the roads so that the gray country and the dark red country began to disappear under a green cover. In the last part of May the sky grew pale and the clouds that had hung in high puffs for so long in the spring were dissipated. The sun flared down on the growing corn day after day until a line of brown spread along the edge of each green bayonet. The clouds appeared, and went away, and in a while they did not try any more. The weeds grew darker green to protect themselves, and they did not spread any more. The surface of the earth crusted, a thin hard crust, and as the sky became pale, so the earth became pale, pink in the red country and white in the gray country.”

So begins The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck’s most famous novel and the one he considered his masterpiece. Published in April 1939 by Viking Press, this Great American Novel is perhaps the most widely read book in the American Canon. In his review of the classic work, John Timmerman said, “The Grapes of Wrath may well be the most thoroughly discussed novel - in criticism, reviews, and college classrooms - of 20th-century American Literature.” Set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, this proletarian novel was Steinbeck’s means of advocating for social change. Written in a conversational style and based on visits he made to numerous migrant camps, this easily accessible tale shares the experience of ‘Okies’ traveling west seeking work, dignity, and a future. They are inextricably tied to the land, which gives them identity and a sense of self. When they lose their land, they lose a part of themselves, the connection with the world around them, which provides their meaning and purpose.

The Grapes of Wrath follows the Joads, a family of tenant farmers driven from their home by economic hardship due to the Dust Bowl, as they migrate from Oklahoma to California. Inspired by handbills advertising jobs in California, they travel along Route 66 with thousands of others, a migrant train leaving everything it had ever known in the hope of finding a life at the end of the journey. They discover that California differs from the promised land they imagined, filled with too many workers and insufficient work. Steinbeck tells the story of the Joads alongside intercalary chapters expounding his broader social commentary related to the story.

Everything Steinbeck had written before this was a training ground for the ideas, philosophies, and themes that found life in this work. More than any other he ever wrote, this intensely human story took a stand on issues important in his day and throughout history. It was a book that was risky to write, personally and professionally. Here, he passionately expounds on the plight of people experiencing poverty and the undeniable truth of human dignity. In a compelling portrait of the conflict between the powerful and powerless, Steinbeck shows how land-owning corporate farmers colluded with government agencies and law enforcement to take advantage of workers, exploiting their rights in the self-serving pursuit of riches. The writing evokes the harshness of the suffering caused by fellow human beings - man’s inhumanity towards man. Our sympathy for the Joads and all like them is aroused, yet their innate goodness and unbreakable pride inspire us. They overcome powerlessness through family, friendship, and community. Steinbeck’s Phalanx theory takes center stage when the migrants persevere, resist, and come together to form a unified whole.

The book provoked extreme reactions, both negative and positive. It was frequently burned and banned from schools and libraries, with critics calling it Communist propaganda. However, it won the National Book Award and later the Pulitzer Prize. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her newspaper column, “Now I must tell you that I have just finished a book which is an unforgettable experience in reading. “The Grapes of Wrath” by John Steinbeck, both repels and attracts you. The horrors of the picture, so well-drawn, make you dread sometimes to begin the next chapter, and yet you cannot lay the book down or even skip a page. Somewhere I saw the criticism that this book was anti-religious, but somehow I cannot imagine thinking of “Ma” without, at the same time, thinking of the love “that passeth all understanding.” The book is coarse in spots, but life is coarse in spots, and story is very beautiful in spots just as life is. We do not dwell upon man’s lower nature any more than we have to in life, but we know it exists and we pass over it charitably and are surprised how much there is of fineness that comes out of the baser clay. Even from life’s sorrows some good must come. What could be a better illustration than the closing chapter of this book?”

Steinbeck wrote to his editor Covici, “I’ve done my damndest to rip a reader’s nerves, I don’t want him satisfied….I tried to write a book the way lives are being lived, not the way books written….Throughout I’ve tried to make the reader participate in the actuality, what he takes from it will be scaled entirely on his own depth or hollowness.” The Grapes of Wrath has certainly fulfilled Steinbeck’s intentions as a story that is raw and true to the lives it intended to represent. Nearly a century later, this book continues to be lauded as the outstanding achievement in Steinbeck’s oeuvre and the American Canon.

I would love to hear from you in the comments. Have you read anything by Steinbeck? What was your impression? Any favorites?

Until next month…

I've read several by Steinbeck. I love The Grapes of Wrath, but I think East of Eden is my favorite. I liked The Winter of Our Discontent, too. I'm intrigued by Working Days. I read Journal on a Novel, from when he was writing East of Eden, and it informed some of my writing practice. I'd also like to give The Long Valley a try.

Fantastic review, thank you. I especially liked what Eleanor Roosevelt said about it, thank you for including that. I can’t wait to see where your Steinbeck journey takes you next!