Achilles Fights the River

The Iliad Book 21

Exploring Life through the Written Word

“So the gods kept clashing, wrangling on, but Achilles kept killing, hacking Trojans down.”

Dear friends,

Book 21 of The Iliad is one of the most violent and mythically charged sections of the epic, set against the tumultuous backdrop of the Scamander River. Following the slaying of Patroclus and the forging of new armor by Hephaestus, Achilles has returned to battle with divine rage. Book 21 opens at a moment of frenzy, with Achilles splitting the Trojan army in two: one half driven toward the city, the other pushed into the Xanthus River (also known as the Scamander). The chapter immediately plunges into carnage, as Achilles slaughters soldiers without mercy, not for tactical advantage but as a manifestation of his insatiable wrath.

Among the first to fall is Lycaon, the son of Priam, who had previously been captured and ransomed by Achilles. Begging for mercy and reminding Achilles of their past encounter, Lycaon tries to appeal to whatever humanity the Greek hero might retain. But Achilles, now hardened by grief and vengeance, dismisses the plea. “Fool, don’t talk to me of ransom,” Achilles snarls, before cutting Lycaon down. It is a chilling moment that signals Achilles’ descent into unrestrained fury—a break from earlier Homeric codes of heroism that allowed for mercy and ransom in war.

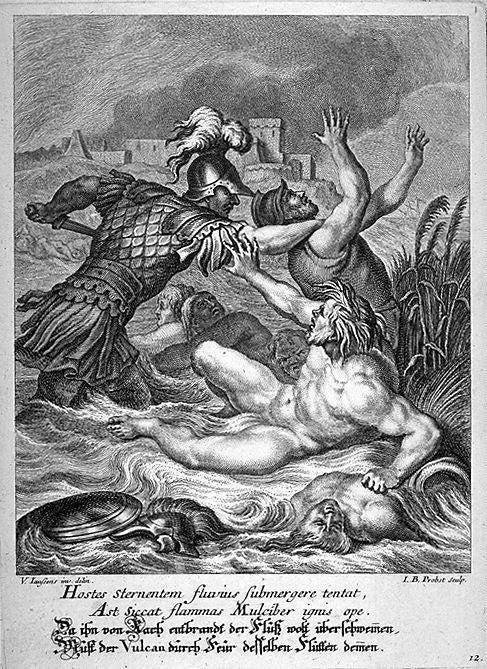

After this brutal killing, Achilles continues his rampage through the river, choking it with corpses. The river god, Scamander (Xanthus), offended by the pollution of his waters, rises in opposition to the demigod. This moment marks a shift from human to divine conflict. The river, personified and divine, attempts to drown Achilles in a wave of liquid fury. Homer describes the tumult with immense force, as the river boils with wrath, hurling trees and torrents at Achilles, who struggles to keep his footing. Scamander is not merely offended by the deaths—he is reacting against hubris and excess, the sense that Achilles has crossed into a realm of inhumanity.

To save Achilles, Hera sends Hephaestus, the god of fire, who sets the plain ablaze with flames so intense they boil the river’s waters. This confrontation—fire against water—brings the narrative to a mythical crescendo. Fire scorches the corpses and repels the river’s advance, forcing Scamander to retreat, and Achilles is saved, not by his own power, but by the intervention of the gods.

Simultaneously, the gods themselves erupt into open conflict. Athena confronts Ares and Aphrodite, mocking and striking them down. Apollo and Poseidon square off, and Artemis is humiliated by Hera. These divine quarrels reflect and exaggerate the human ones, adding a layer of absurdity and comedy to the deadly seriousness of the mortal battlefield. This divine battle underscores how entangled the gods are in the affairs of mortals, their feuds mirroring and distorting human struggles.

The book concludes with Achilles continuing his bloodshed. He captures twelve Trojan youths to sacrifice at the funeral of Patroclus, a gesture that evokes the older, darker traditions of warfare and sacrifice. Priam’s son Agenor then bravely stands against Achilles, buying precious time for the retreating Trojans. Just as Achilles is about to kill Agenor, Apollo intervenes, enveloping the prince in a mist and luring Achilles away by assuming Agenor’s form. This allows the Trojans to flee back within their city walls. The book ends with the Trojans narrowly escaping annihilation, Achilles relentless and godlike, standing outside their gates.

Book 21 of The Iliad is perhaps the most unflinching portrait of Achilles as a figure transformed by wrath into something less than human—or more than human. The lines between hero and monster blur. Homer crafts this book as a climax of violence and divine spectacle, where the hero's descent into savagery is matched only by the chaos of nature and the gods reacting in alarm.

Achilles' rejection of Lycaon's plea represents a profound turning point. In earlier books, such as in his interactions with Priam at the end of the poem, Achilles shows the capacity for pity and shared human grief. But here, grief has not softened him—it has calcified his rage. His killing of Lycaon is not just an act of violence but a philosophical rejection of the shared values that held the warrior code together. By spurning ransom and mercy, Achilles defies the very customs that separate heroes from butchers.

The river god Scamander's rebellion against Achilles dramatizes the world itself pushing back against Achilles’ excess. Homer anthropomorphizes the river, turning it into a moral force, and the battle becomes not just man versus nature, but man versus the very boundaries of mortal behavior. Scamander’s assault is not simply about physical pollution, but spiritual and moral transgression. Achilles is portrayed almost as a force of nature, a whirlwind of destruction that must be restrained.

And indeed, the gods themselves cannot ignore Achilles any longer. Their intervention—Hephaestus wielding fire to save Achilles from the drowning river—suggests that only divine interference can check the hero’s momentum. Yet the gods, in their squabbling, often come across as petty or laughable. Hera boxes Artemis’ ears. Athena knocks out Ares. Homer juxtaposes the cosmic and the comical, suggesting that divine power does not always equate to divine wisdom or nobility. Their battles, while entertaining, reduce Olympus to a parody of mortal war.

This collapse of order—both moral and cosmic—is one of the deeper themes of Book 21. Achilles’ grief, untethered from the social norms that once guided him, becomes apocalyptic. He sacrifices twelve boys in a brutal preview of his offering to Patroclus’ shade, an act Homer treats with ambivalence. The ritual, while traditional, is archaic and brutal, another sign that Achilles now dwells at the edge of civilization, closer to myth than to man.

The episode with Apollo impersonating Agenor is both tactical and symbolic. The gods must deceive Achilles to delay him. Even as he stands as an unstoppable force, Achilles is manipulated, showing that even the greatest warrior is ultimately a pawn on a divine chessboard. Yet this also signals a kind of equilibrium: despite Achilles’ might, the universe will not allow total annihilation. Fate, divine will, and mortal courage all work in tandem to preserve some balance.

In modern terms, Book 21 holds a mirror to our own struggles with violence, rage, and the limits of power. Achilles’ descent into unchecked vengeance resonates in an era where grief often begets cycles of retribution, where mercy is perceived as weakness, and where moral boundaries are easily erased by trauma. His transformation challenges us to consider what happens when individuals or societies forsake moderation and justice in the name of righteous fury.

The river’s protest also carries ecological and ethical overtones that feel especially timely. Nature is not silent—it revolts when pushed too far. Achilles is not just a slayer of men; he becomes a pollutant, a desecrator of the natural order. Scamander’s resistance is a metaphor for the earth crying out against human destructiveness. In this light, the scene might be read as an early mythic recognition that nature has its own agency—and its own breaking point.

The divine comedy interlaced within the tragedy—gods bickering and brawling—feels eerily familiar in a world where the powerful often seem disengaged from the consequences of their actions. The gods in The Iliad mirror the dysfunction of leadership when ego, jealousy, and vanity replace stewardship and responsibility. Yet Homer does not suggest that all power is corrupt—rather, he shows how easily it can be misused when those wielding it are unmoored from virtue.

Furthermore, the spectacle of Achilles in Book 21 invites reflection on the cult of the hero in contemporary life. Our own cultural narratives—whether in politics, celebrity, or war—often elevate figures of great strength, charisma, or vengeance. But Achilles in this book is no longer a noble hero; he is an engine of annihilation. Homer’s portrayal warns us against the allure of unchecked power, against conflating grief with license, and against glorifying violence for its own sake.

Finally, the subtle thread of resistance—embodied in Agenor’s stand—offers a glimmer of modern hope. Even in the face of overwhelming force, courage is not extinguished. It is no coincidence that Agenor’s defiance buys time for the Trojan retreat. One man, standing firm, shapes the fate of thousands. In our time, too, acts of courage—even symbolic ones—can disrupt narratives of inevitability, violence, or domination.

Book 21 of The Iliad is a terrifying and majestic whirlwind of violence, divine intervention, and mythic proportions. It marks the height of Achilles’ wrath and the unraveling of the heroic code that has governed much of the poem. In its depiction of war’s consequences—on nature, the divine order, and the human soul—it transcends its ancient setting to speak to perennial concerns.

Achilles in this book is a warning and a mirror. He is both larger than life and tragically human: a man devoured by grief and exalted by power, but ultimately diminished by his refusal to yield. Homer does not absolve him, but neither does he condemn him absolutely. Instead, he offers a poetic meditation on the cost of rage, the fragility of balance, and the stubborn hope of resistance.

We may not fight our battles with swords beside rivers, but we still grapple with the same storms of emotion, the same temptations of vengeance, and the same need to ask: What makes a hero, and at what cost do we let our wrath rule the world?

“The river burst into a boil, seething with foam and blood and bodies of the dead.”

History and Mythological Context

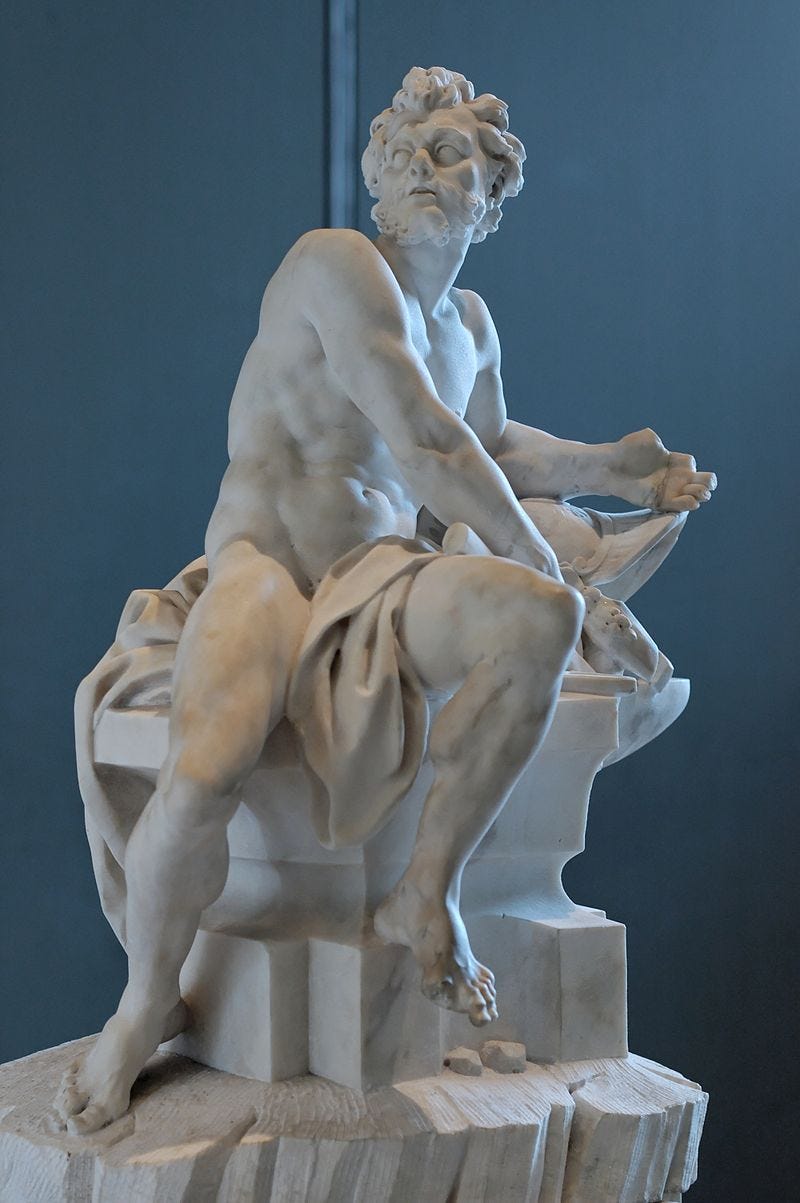

Hephaestus, the Greek god of fire, metallurgy, and craftsmanship, occupies a distinct and often paradoxical place within the pantheon of Greek mythology. Unlike the gods who exude beauty, power, or wisdom in seamless form, Hephaestus is portrayed as imperfect—physically disabled, socially marginalized, and frequently the object of ridicule. Yet, he is also one of the most indispensable deities of Olympus, the master of divine invention and creator of the very tools the gods use to exert their power. His mythological history is deeply rooted in both the artistic spirit of the ancient world and the enduring theme of resilience through adversity.

The origin of Hephaestus is a tale of divine contradiction. According to some traditions—most notably Homer’s Iliad—Hephaestus is the son of Zeus and Hera. In other accounts, particularly those popular in Hesiod's writings, Hera bore Hephaestus alone, in retaliation against Zeus for birthing Athena without a mother. Hera’s motive was not maternal love but rivalry, and the result was a god who from his very inception was caught in the crossfire of divine politics.

Crucially, Hephaestus was born lame, a physical impairment that set him apart from his fellow gods. The Olympians, paragons of aesthetic perfection, found this deformity intolerable. In one account, Hera, ashamed of her imperfect son, cast him from Olympus. In another version, it is Zeus who hurls Hephaestus down after he takes Hera’s side during a quarrel. In either case, Hephaestus plummets to earth, landing in the sea where he is rescued and raised by the sea goddesses Thetis and Eurynome. This period of exile, isolation, and foster care away from Olympus shapes the identity of Hephaestus as a god outside the usual mold—both physically and socially.

Yet Hephaestus is not consumed by bitterness. Instead, he learns to work with his hands, crafting wonders from metal, fire, and imagination. When he eventually returns to Olympus, his tools—not his strength—grant him leverage. In a clever act of vengeance, he creates a golden throne for Hera, which ensnares her upon sitting. None of the gods can free her. It is only through the persuasive power of Dionysus, who intoxicates Hephaestus and brings him back to Olympus, that the trap is undone. The gods, recognizing his immense skill, accept him once more into their fold.

This mythic cycle—from rejection and exile to return and indispensability—underscores Hephaestus’ enduring importance. He is the divine forger, builder of palaces, thrones, weapons, and automatons. His creations include the armor of Achilles, the scepter of Agamemnon, the golden dogs of Alcinous, and even Pandora, the first woman. While other gods wield thunder, war, or wisdom, Hephaestus wields ingenuity—the power to create that which did not previously exist.

Role in Ancient Literary Works

Hephaestus appears in numerous ancient texts, though his roles are often peripheral rather than central. Yet each appearance is rich in symbolic meaning. In Homer’s Iliad, Book 1, he plays a conciliatory role, attempting to defuse the tension between Zeus and Hera with humor and tact. "It’s hard to fight with your wife,” he says, limping around the hall and bringing laughter to the gods. Here, he is not a warrior but a mediator—valued for his diplomacy as well as his craft.

In The Iliad, Book 18, his most important literary moment arrives when he forges the armor of Achilles at Thetis’ request. This scene is one of the most visually striking in all of Homeric literature. Hephaestus labors at his forge, surrounded by golden automatons—self-moving machines who assist him as helpers. The process is described in vivid, almost reverent detail. The shield of Achilles becomes a cosmos unto itself, etched with images of war and peace, harvest and celebration. Hephaestus here is not merely a smith—he is a creator of worlds. The artistry and symbolism of the shield suggest that craftsmanship is not merely technical labor but an act of divine storytelling and philosophical reflection.

In Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days, Hephaestus appears in connection with Pandora, the first woman created as a punishment for man. Ordered by Zeus, Hephaestus forms her out of clay and imbues her with beauty and charm. Though the myth reflects a deeply misogynistic worldview, it also underscores the ambivalence surrounding the creative act. Hephaestus can give life—but life, in this case, brings suffering. Even in divine craftsmanship, there is an edge of danger, of unintended consequence.

Later Greek dramatists and poets use Hephaestus more sparingly, though he figures prominently in Aeschylus’ tragedy Prometheus Bound. In this play, Hephaestus is ordered to bind Prometheus to a rock as punishment for stealing fire and giving it to humanity. He does so reluctantly, lamenting the cruelty of Zeus. His role here is ethically complex: the obedient craftsman caught between compassion and duty.

The Roman poet Virgil also adapted Hephaestus into his mythology under the name Vulcan. In the Aeneid, Vulcan forges the arms of Aeneas at the behest of Venus, echoing his role in the Iliad. Again, the motif is one of divine craftsmanship for a mortal hero whose fate will shape civilizations. Through Roman reinterpretation, Hephaestus becomes a guardian of empire and order, yet the tension between his rough appearance and transcendent skill remains.

Hephaestus as a Deity

Unlike other Olympian gods, Hephaestus represents labor rather than dominion. He is not a ruler of seas or skies, not a god of war or wisdom. Instead, he is the god of creation, of work, of the forge—the patron of blacksmiths, artisans, engineers, and sculptors. His realm is not Mount Olympus, but the subterranean depths, the volcanic forges, the anvils and embers of the human world.

His dual residence—among the gods and apart from them—reinforces his role as a bridge between divine and mortal spheres. In many ways, Hephaestus is the most "human" of the gods. He suffers, labors, creates, and is mocked or overlooked. He is married, somewhat unhappily, to Aphrodite, who famously betrays him with Ares. This marriage—often read as comic or ironic—reflects deeper themes about appearance and worth. While Aphrodite is the goddess of beauty, Hephaestus is the god of utility. Their union is symbolic of the tension between aesthetic and functional value.

Despite his marginality, Hephaestus is powerful in his own right. He creates automatons, weapons, and devices far beyond the reach of other gods. His workshop is a space of miraculous invention, filled with technology that borders on science fiction. In the age of Homer, the concept of self-moving machines or intelligent assistants would have seemed like pure fantasy—yet Hephaestus imagines and builds them. In this sense, he is not only a god of fire and metal, but of technological prophecy.

Hephaestus also possesses an innate moral complexity. Unlike gods who act with impulsive cruelty, he often hesitates, reflects, and even expresses compassion. His obedience to Zeus is tempered by reluctance. He does not seek revenge, even when scorned. His role is never one of domination but of service—and yet through that service, he exercises immense creative power.

Modern Relevance and Relatable Traits

Hephaestus endures as one of the most relatable figures in Greek mythology, particularly in the modern age. In an era that celebrates innovation, technical skill, and problem-solving, Hephaestus emerges as a divine prototype of the inventor, the engineer, the craftsman, and the underdog genius. His character prefigures the modern archetype of the brilliant outsider—the one who, though physically limited or socially excluded, contributes immeasurably through intellect and creativity.

One of the most powerful aspects of Hephaestus is his perseverance. Rejected by his mother, thrown from heaven, ridiculed by his peers—he could have descended into bitterness. Instead, he channels his suffering into work. His forge becomes not only a place of labor but of redemption. This makes him a figure of resilience, reminding us that adversity can be transmuted into artistry.

His physical disability, rather than diminishing his value, becomes part of his identity as a god who creates despite pain. In a modern context that seeks to embrace diversity and recognize the contributions of people with disabilities, Hephaestus offers a counter-narrative to the myth of the perfect hero. He is not swift like Hermes or strong like Ares, but he is essential. He shows that value lies not in conforming to ideals of physical perfection but in forging one's unique path.

Furthermore, Hephaestus' role as a mediator and reluctant enforcer makes him morally compelling. He does what is asked of him, but not without reflection. His compassion for Prometheus and loyalty to Thetis, who once saved him, suggest a depth of character that extends beyond duty. He is capable of kindness, humor, humility, and ingenuity—traits deeply human and deeply needed.

In a world increasingly reliant on technology, artificial intelligence, and mechanization, Hephaestus feels eerily prescient. His automatons prefigure modern robotics. His ability to animate lifeless matter echoes the dream of AI. Yet his creations always serve a human or divine purpose—they are extensions of will, not substitutes for it. As we contemplate the ethical boundaries of technology, Hephaestus reminds us that invention must be tempered with wisdom, that the maker bears responsibility for the world he helps shape.

Finally, Hephaestus’ narrative offers a meditation on the nature of creativity itself. True creation is often born not of triumph but of struggle. It requires solitude, fire, and persistence. The forge is a place of transformation—of metal, of mind, of meaning. Through Hephaestus, we glimpse the sacredness of work, the dignity of the unseen laborer, and the quiet power of those who build rather than destroy.

Conclusion

Hephaestus stands as a paradoxical figure in the Greek pantheon—deformed yet divine, ridiculed yet revered, cast out yet indispensable. He is a god of fire not for its destructive force but for its creative potential. His myths, though often marginalized in the grand narratives of Olympus, carry deep resonance: about the value of labor, the resilience of the outsider, and the sacredness of creation.

In our modern world—brimming with technology, inequality, and the search for meaning—Hephaestus speaks across millennia. He reminds us that greatness does not always come in beautiful forms, that genius may limp but still soar, and that the truest gods may be those who dwell not in palaces of power, but in the glowing, hidden depths where vision is shaped by flame and hammer.

Hephaestus does not rule, but he builds the world in which others rule. In doing so, he reveals that the creator—though often unseen—is always divine.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

What does Achilles’ refusal to spare Lycaon suggest about the transformation of his character?

How does his rejection of mercy contrast with earlier portrayals of heroic values in The Iliad, and what does this say about the psychological cost of grief and rage?In what ways does nature (through the personified river Scamander) act as a moral force in Book 21?

How can this episode be interpreted as a commentary on the consequences of excess—either in war or in our treatment of the environment?What is the significance of the gods’ open combat in this book?

Does Homer use these divine battles to elevate or undermine the seriousness of the mortal conflict, and how might this reflect the poet’s view of divine authority or leadership in general?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 22. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Death of Hector and covers pages 541-558. In the Wilson translation, it is called A Race to Death and covers pages 525-544.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Another layered read! As only an enthusiastic amateur, you bring Book 21 to life with nuance, urgency, and modern resonance. This is especially true of environmental and emotional insights. I’ll never read Achilles’ fury or Hephaestus’ fire the same way again.

Stewardship of our environment. What’s our responsibility and what happens when we don’t take that seriously?

The environment always gets a vote. This actually aligns with the broader theme of outcomes being out of our hands that’s been screaming at me throughout the book.