Exploring Life through the Written Word

“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns, driven time and again off course, once he had plundered the hallowed heights of Troy.”

Dear friends,

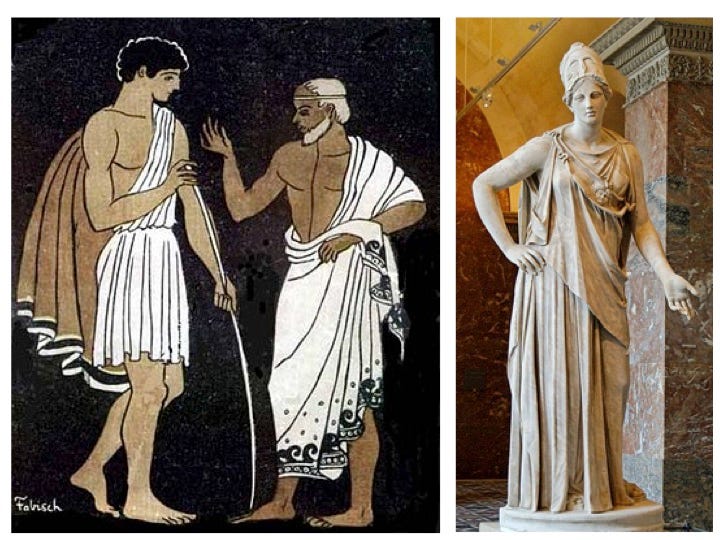

Book 1 of Homer's The Odyssey serves as both prologue and catalyst, establishing the epic's central conflicts while setting in motion the events that will drive the narrative forward. The book opens with the famous invocation to the Muse, where Homer requests divine assistance in telling the story of Odysseus, "that man of twists and turns" who wandered far after the fall of Troy. This opening immediately establishes the epic's scope and introduces us to its complex protagonist, a hero defined not merely by physical prowess but by his intellectual cunning and his profound suffering.

The narrative proper begins on Mount Olympus, where the gods are gathered in council. Athena, goddess of wisdom and warfare, pleads with her father Zeus to intervene on behalf of Odysseus, who has been trapped on Calypso's island for seven years. The timing of this divine intervention is crucial: Poseidon, Odysseus's primary divine antagonist, is away visiting the Ethiopians, creating an opportunity for the other gods to act. Zeus agrees to send Hermes to Calypso with orders to release Odysseus, while Athena herself will travel to Ithaca to inspire Telemachus, Odysseus's son, to take action.

The scene then shifts dramatically from the celestial realm to the very earthly problems of Ithaca. Here we encounter Telemachus, now a young man of twenty, living in a household under siege. For three years, 108 suitors have occupied his family's palace, consuming their wealth while pressuring his mother Penelope to choose a new husband. These suitors represent more than mere romantic rivals; they embody a complete breakdown of the social order that should protect the family of an absent hero.

Athena arrives in Ithaca disguised as Mentes, an old family friend and trading partner. She finds Telemachus sitting apart from the suitors, lost in thought and clearly distressed by the situation in his home. The goddess approaches him with both comfort and challenge, first listening to his complaints about the suitors' behavior, then urging him to take decisive action. She suggests that he call an assembly of the Ithacan nobles to publicly denounce the suitors' behavior, and then embark on a journey to seek news of his father from Nestor in Pylos and Menelaus in Sparta.

This conversation with Athena marks a crucial turning point for Telemachus. Throughout their dialogue, we see him transform from a passive, dejected young man into someone beginning to recognize his own agency and responsibility. The goddess's words awaken in him a sense of his own identity and potential power. When she departs, Telemachus is left with new resolve, though he does not yet fully understand the divine nature of his visitor.

The book concludes with Telemachus confronting the suitors more boldly than before, particularly Antinous and Eurymachus, their ringleaders. When they mock his newfound confidence and question the identity of his mysterious visitor, Telemachus responds with a dignity and authority that surprises them. However, the suitors remain defiant, and the book ends with the household retiring for the night, the tensions unresolved but the stage set for the conflicts to come.

This opening book masterfully establishes the epic's key themes while creating forward momentum through both divine intervention and human awakening. Homer presents a world where gods and mortals interact in complex ways, where divine will and human agency intertwine, and where the restoration of proper order necessitates both supernatural assistance and mortal courage.

Book 1 reveals Homer's sophisticated understanding of the relationship between divine intervention and human responsibility. The council of the gods that opens the narrative is not merely a convenient plot device but a profound meditation on justice, both cosmic and human. When Athena pleads Odysseus's case before Zeus, she frames his plight in terms of justice and merit. Odysseus, she argues, has suffered enough for any offenses he may have committed, and his continued imprisonment by Calypso violates the cosmic order.

Zeus's response is equally significant. Rather than simply decreeing Odysseus's release, he sets in motion a complex chain of events that will require both divine assistance and human effort. Hermes will carry the gods' message to Calypso, but Odysseus must still find the courage and skill to leave her island and complete his journey home. Similarly, Athena will inspire and guide Telemachus, but the young man must find within himself the strength to challenge the suitors and undertake his quest for news of his father.

This interplay between divine will and human agency reflects a worldview in which the gods are neither absent nor all-controlling. They establish the framework within which human action becomes possible, but mortals must still choose to act courageously and wisely within that framework. This theme resonates throughout the epic, reflecting the complex moral universe that Homer creates —a universe in which both divine justice and human virtue are necessary for the restoration of proper order.

Perhaps the most psychologically compelling aspect of Book 1 is the portrayal of Telemachus's awakening to his own identity and responsibilities. At the book's opening, he is trapped in a kind of prolonged adolescence, neither child nor fully adult, paralyzed by circumstances beyond his control. The suitors have invaded his home, consumed his inheritance, and threatened his family's honor, yet he lacks both the physical power and the social authority to expel them.

Athena's intervention represents more than divine assistance; it serves as a catalyst for psychological and moral development that must ultimately come from within Telemachus himself. The goddess does not solve his problems for him but rather helps him recognize his own capacity for action. She reminds him of his noble lineage, his right to inheritance, and his responsibility to protect his family's honor. Most importantly, she helps him see that his current passivity is itself a choice, and that he has the power to choose differently.

The transformation is not immediate or complete. Telemachus continues to struggle with self-doubt and inexperience throughout the epic. However, Book 1 marks the crucial beginning of his journey toward manhood, a journey that will parallel and complement his father's journey home. In this way, Homer creates a double plot structure in which father and son, separated by distance and circumstance, undergo parallel processes of testing and growth.

The situation in Ithaca as presented in Book 1 represents a complete breakdown of the social order that should govern aristocratic Greek society. The suitors' behavior violates multiple fundamental principles: the laws of hospitality (xenia), which should protect guests but not allow them to abuse their hosts; the respect due to the family of a hero; and the proper procedures for courtship and marriage. Their occupation of Odysseus's palace and consumption of his wealth represents not just personal wrongdoing but a threat to the stability of the entire community.

Homer's portrayal of this breakdown is particularly sophisticated in its attention to the economic dimensions of the crisis. The suitors are not merely eating Odysseus's food; they are systematically destroying the economic foundation that supports not only his immediate family but the broader network of dependents, servants, and retainers who rely on the household's prosperity. Telemachus's complaint that they are consuming his inheritance is not merely personal grievance but recognition that the entire social structure of his world is under threat.

The absence of effective leadership compounds the crisis. With Odysseus gone and no clear mechanism for resolving the situation, Ithaca exists in a state of political limbo. The suitors recognize no authority higher than their own desires, while the other nobles seem powerless or unwilling to intervene. Only divine intervention, channeled through the awakening of Telemachus, offers hope for restoration of proper order.

Homer's narrative technique in Book 1 demonstrates his mastery of epic convention while also revealing innovations that make The Odyssey unique among ancient epics. The invocation to the Muse follows traditional patterns but introduces Odysseus in terms that emphasize his psychological complexity rather than his martial prowess. The council of the gods provides the cosmic framework typical of epic poetry, but Homer uses this divine assembly to explore questions of justice and suffering that give the epic its philosophical depth.

The use of dramatic irony is particularly effective throughout Book 1. The audience knows that Athena appears to Telemachus in disguise, but he does not recognize her divine nature until after she has departed. This creates a layered reading experience in which we simultaneously follow Telemachus's limited perspective and appreciate the fuller cosmic significance of the events we witness.

Homer's characterization techniques also deserve attention. Rather than providing static descriptions of his characters, he reveals their personalities through their actions and speeches. Telemachus's initial passivity, the suitors' arrogance, and Athena's wise guidance all emerge through dialogue and behavior rather than authorial exposition. This dramatic method of characterization gives the narrative immediacy and allows readers to form their own judgments about the characters' moral worth.

The World of the Greek Dark Age

The Odyssey was composed during the eighth century BCE, but it depicts a world that Homer and his audience understood to be ancient even by their standards. The society portrayed in the epic reflects the aristocratic warrior culture of the Greek Dark Age (roughly 1200-800 BCE), a period following the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization that had dominated the Greek world during the Bronze Age.

The social structures depicted in Book 1 reflect this historical context. The household of Odysseus represents the oikos, the fundamental economic and social unit of archaic Greek society. The oikos was more than a mere family; it included extended kin, retainers, servants, and slaves, all bound together in a complex web of mutual obligations and dependencies. The prosperity of the oikos depended on the leadership of its head, and his absence or weakness could threaten the survival of everyone within the household.

The suitors' behavior would have been immediately recognizable to Homer's audience as a violation of fundamental social norms. The institution of xenia (guest-friendship) was crucial to the functioning of archaic Greek society, enabling trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange across the scattered communities of the Greek world. The suitors abuse this institution, transforming from guests into parasites who threaten the very foundation of their host's household.

The political situation in Ithaca also reflects historical realities of the Dark Age. In the absence of strong central authority, local communities were governed by assemblies of nobles who were expected to reach consensus on important matters. Telemachus's plan to call such an assembly represents an appeal to traditional forms of authority, though the effectiveness of such institutions depended on the willingness of the participants to respect traditional norms.

The themes explored in Book 1 of The Odyssey resonate powerfully with contemporary concerns and experiences. The breakdown of social order depicted in Ithaca mirrors situations in modern societies where traditional institutions and authorities have lost their effectiveness, creating power vacuums that opportunistic individuals or groups attempt to fill.

The economic dimension of the crisis in Ithaca has particular relevance to contemporary discussions about inequality and the concentration of wealth. The suitors represent a kind of predatory behavior that extracts value from productive enterprises without contributing to their growth or sustainability. Their systematic consumption of Odysseus's wealth while contributing nothing to the household's prosperity parallels modern concerns about extractive economic practices that benefit a few at the expense of the many.

Telemachus's psychological journey from passivity to agency speaks to universal human experiences of coming of age and finding one's voice in difficult circumstances. His struggle to assert legitimate authority in the face of those who refuse to recognize it reflects challenges faced by many people in contemporary society, from young professionals establishing themselves in competitive fields to community leaders working to address systemic problems.

The role of mentorship depicted in Athena's relationship with Telemachus also has contemporary relevance. The goddess's approach combines emotional support with practical guidance, helping Telemachus recognize his own capabilities while providing him with concrete steps he can take to improve his situation. This model of mentorship, which empowers rather than creates dependency, remains relevant to educational, professional, and personal development contexts today.

Book 1 raises questions about leadership and responsibility that remain relevant to contemporary political and social discourse. Odysseus's absence has created a leadership vacuum that various parties attempt to fill in different ways. The suitors claim authority through force and numbers, while Telemachus must learn to claim his legitimate inheritance through moral authority and traditional right.

The question of what constitutes legitimate authority is central to the book's political themes. The suitors have physical power and social support among themselves, but they lack the moral foundation that would make their authority legitimate. Telemachus has traditional right and moral claims, but he lacks the practical power to enforce his will. Only through the intervention of divine justice, channeled through human agency, can legitimate authority be restored.

This tension between power and legitimacy speaks to contemporary debates about governance, leadership, and social change. The epic suggests that sustainable social order requires not merely the exercise of power but the alignment of power with justice and traditional values. At the same time, it recognizes that such alignment sometimes requires active intervention to restore proper relationships when they have been disrupted.

Modern readers may also find in Book 1 insights into the psychology of trauma and recovery that remain relevant to contemporary understanding of these processes. Telemachus's initial passivity can be understood as a response to prolonged stress and uncertainty. Living for years in a household under siege has clearly affected his psychological development, leaving him uncertain of his own identity and capabilities.

Athena's intervention provides what contemporary psychology might recognize as a form of therapeutic intervention. She helps Telemachus reframe his situation, recognize his own agency, and develop concrete plans for positive action. Her approach combines validation of his legitimate grievances with challenge to take responsibility for changing his circumstances.

The emphasis on storytelling and the search for information about Odysseus also reflects the importance of narrative in processing traumatic experiences. Telemachus's planned journey to seek news of his father represents not merely a quest for factual information but a need to understand his own story and place within the larger narrative of his family's history.

Book 1 of The Odyssey demonstrates Homer's extraordinary ability to weave together divine and human concerns, creating a narrative that operates simultaneously on cosmic and intimate scales. The book establishes the epic's central conflicts while introducing themes that will resonate throughout the work: the relationship between divine justice and human agency, the process of maturation and self-discovery, the fragility and importance of social order, and the power of storytelling to shape understanding and inspire action.

The genius of Homer's approach lies in his ability to make these grand themes accessible through vivid, psychologically compelling characters whose struggles and growth feel authentic despite the epic's supernatural elements. Telemachus's awakening to his own possibilities, Athena's wise guidance, and even the suitors' arrogant blindness to the consequences of their actions all reflect recognizable human experiences elevated and illuminated by the epic's larger vision.

Perhaps most importantly, Book 1 establishes the epic's fundamental optimism about the possibility of restoring justice and order through the combination of divine grace and human courage. While it does not minimize the real difficulties faced by its characters, it suggests that even seemingly impossible situations can be transformed when divine wisdom meets human willingness to act with courage and integrity.

This vision remains as relevant today as it was nearly three millennia ago, offering hope that contemporary challenges, no matter how overwhelming they may seem, can be addressed through the same combination of moral clarity, practical wisdom, and determined action that Homer celebrates in his timeless epic.

“You must not cling to your boyhood any longer— it’s time you were a man. Haven’t you heard what glory Prince Orestes won throughout the world…”

Study Questions

What does Athena's approach to helping Telemachus suggest about the proper relationship between supernatural assistance and personal growth? Consider how this theme might relate to contemporary views on fate, luck, and personal responsibility.

Trace Telemachus's emotional and psychological journey throughout Book 1. What specific changes do you observe in his behavior and self-perception after his encounter with Athena? How does Homer portray the transition from adolescence to adulthood, and what does this suggest about the challenges of coming of age in any era?

Examine the concept of xenia (guest-friendship) as it appears in Book 1, both in its violation by the suitors and its proper expression through Athena's disguised visit. What does Homer suggest about the importance of hospitality and reciprocal relationships in maintaining social cohesion? How do these ancient values relate to contemporary ideas about community and mutual responsibility?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 2. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled “Telemachus Sets Sail” and covers pages 93-106. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled “A Dangerous Journey” and spans pages 120-134.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription costs only $12 per year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

After our break from the Iliad, I was happy to turn to the Odyssey and Matthews excellent and thought-provoking essays. For additional background and context, I highly recommend that readers of the Fagles translation take the time to read the introduction.

Regarding the first question you pose, it is interesting to compare and contrast the role of divine intervention in the Iliad with what we have seen so far in the Odyssey. In the Iliad, we learned that divine will and action are not necessarily supreme, but are subject to fate. In Book one of the Odyssey, we learn that divine intervention can lay the ground work (or first principles) for human action, but that human choices in reaction to the intervention/first principles ultimately determine the outcome. Combining these two lessons, does this mean that human agency (freewill) is the sine qua non of fate? It's an interesting question to ponder.

I can't really put my finger on why, but so far the Odyssey seems more modern to me than the Iliad. Maybe it's because the the Iliad is about an epic battle of ancient armies layered with very personal interactions, while the Odyssey feels like an adventure/mystery story with palace intrigue, personal quest against long odds and ultimate triumph of personal courage - themes we see throughout modern literature and popular culture.

After two intelligence and well said comments, I’m just going to say I’m grasping the story and the concepts which - I’m very happy about. I agree The Odyssey is timeless and reflects the way of humans then and now. A great beginning.