Exploring Life and Literature.

"He lashed the two with his staff, filled their hearts with fighting strength, filled their legs with speed and their arms with power. Then he flashed away, like a swift-winged hawk soaring high from a sheer rock face, blazing for miles in the sun’s light."

Dear friends,

Book 13 is a crucial turning point in the epic. It presents a moment when the tide of battle seems perilously close to delivering the Achaean fleet into Trojan hands. With Zeus having turned his gaze away from the battlefield, Poseidon seizes the opportunity to intervene, stirring hope and strength into the beleaguered Greeks. The chapter unfolds with gripping combat scenes, stirring speeches, and the gods’ manipulation of fate. Though separated from us by millennia, the themes of leadership, courage, and the struggle against despair remain as relevant in the modern age as they were in Homer’s time.

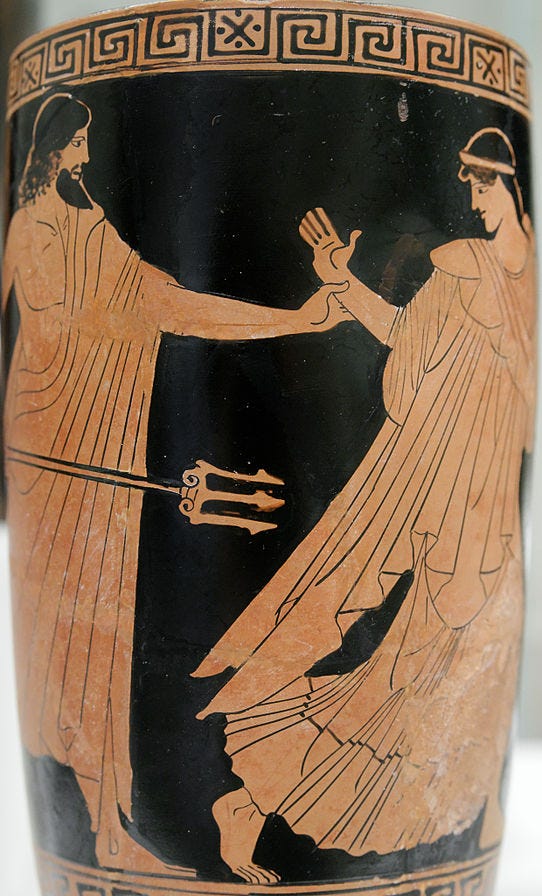

After the events of Book 12, where Hector and the Trojans breached the Achaean wall, Book 13 opens with the Greeks in dire straits. Zeus turns his attention away from the battlefield, convinced that the Trojans’ victory is inevitable. This divine inattention creates an opportunity for Poseidon, god of the sea and the earth-shaker, to act without interference. Enraged by the Trojan threat to the Greek fleet, Poseidon takes on the guise of Calchas, the seer, and stirs the Achaeans into action.

Poseidon, driven by partiality for the Greeks, inspires their captains, giving them the courage they desperately need. He first approaches the two Ajaxes—Telamonian Ajax, a towering warrior, and Ajax, son of Oïleus, known for his speed and ferocity. With godly authority, Poseidon rejuvenates their spirits, filling them with strength and defiance. The image of Poseidon, streaking across the battlefield like a hawk, underscores the divine speed and potency of his intervention. Through his influence, the Achaeans rally, holding the line against the Trojan onslaught.

A major highlight of this book is the aristeia, or the moment of battlefield excellence, of Idomeneus, the Cretan king. Inspired by Poseidon’s intervention, Idomeneus charges into battle with unrelenting ferocity. His presence is described in gloriously brutal imagery as he cuts through the Trojan ranks. The scene pulses with vivid depictions of gore and valor. Idomeneus slays Othryoneus, who had sought the hand of Priam’s daughter in exchange for his service in the war. When Idomeneus kills him, he taunts the corpse with bitter irony, mocking his failed ambitions.

"Poor fool, the marriage you courted

will never come true—you’ll meet your death at my hands!"

(The Iliad, 13.385–386, Fagles)

The brutal jeering reflects the savagery of battle, where ambition and hope are dashed by the spear. Idomeneus then slays Asius, Hyperenor, and Alkathous, his wrath leaving a trail of carnage. His aristeia marks the Greek resurgence, stalling the Trojans' advance.

Hector, the great Trojan prince, remains undeterred by the Greek resistance. Though the gods inspire the Achaeans, Hector continues to press forward. His battle-fury is depicted as nearly godlike in its ferocity, a mortal force of nature driving the Trojans onward. Homer’s description of Hector as a storm or a wildfire captures the unstoppable momentum of his rage.

"And Hector swept in,

breaking the front like a sudden squall,

blasting dark on the raging seas,

bearing down with giant-killing Zeus’s power,

plunging, driving the ship’s crew frantic,

terrified to death—they grip what they can,

death racing at them, all their minds deranged."

(The Iliad, 13.795–800, Fagles)

This passage paints an image of Hector’s terrifying prowess. His charge embodies both physical force and psychological dominance, driving panic into the Achaean ranks.

Poseidon's intervention and the leadership of Idomeneus highlight the critical importance of morale and inspiration during adversity. In modern contexts, this reflects how strong, decisive leadership can turn the tide of despair in times of crisis. Whether in war, politics, or moments of personal struggle, figures who inspire resilience and unity play a vital role. Poseidon's actions, though driven by divine power, mirror the way human leaders can instill hope and strength through words and action.

The unflinching depiction of battlefield gore also offers a sobering reflection on the violence and futility of war. The human cost of conflict—depicted through Idomeneus' ruthless slaughter and the anguished cries of the dying—is as poignant today as it was in Homer’s time. The senseless destruction, ambition, and loss reflect the tragic realities of modern warfare. The taunting of Othryoneus’ corpse symbolizes the dehumanizing effect of prolonged violence—a chilling reminder of how war strips away compassion and dignity.

In this book, we also explore the paradox of fate and free will. While the gods intervene, the human characters still make their own choices. Idomeneus could have fled but instead chooses to stand his ground. Similarly, modern individuals face moments where their actions, despite circumstances beyond their control, determine their character. Whether resisting oppression or battling personal hardship, the human will to fight, despite the apparent inevitability of fate, is a timeless struggle.

The resilience of the human spirit in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds is on show in this book. The Achaeans, driven by Poseidon's divine intervention, manage to resist the Trojans’ onslaught. The book’s stirring battle scenes, memorable acts of heroism, and the unyielding fury of Hector encapsulate both the glory and the horror of war. In the modern world, the themes of leadership, perseverance, and the human cost of conflict continue to echo. Through Homer’s immortal verse, we are reminded that the struggles of antiquity remain deeply entwined with the human condition.

"But now Poseidon, holding his trident, the Earthshaker, strode among the Argives, urging them on, building the spirit and strength in each man’s heart, and rousing the ranks to fight."

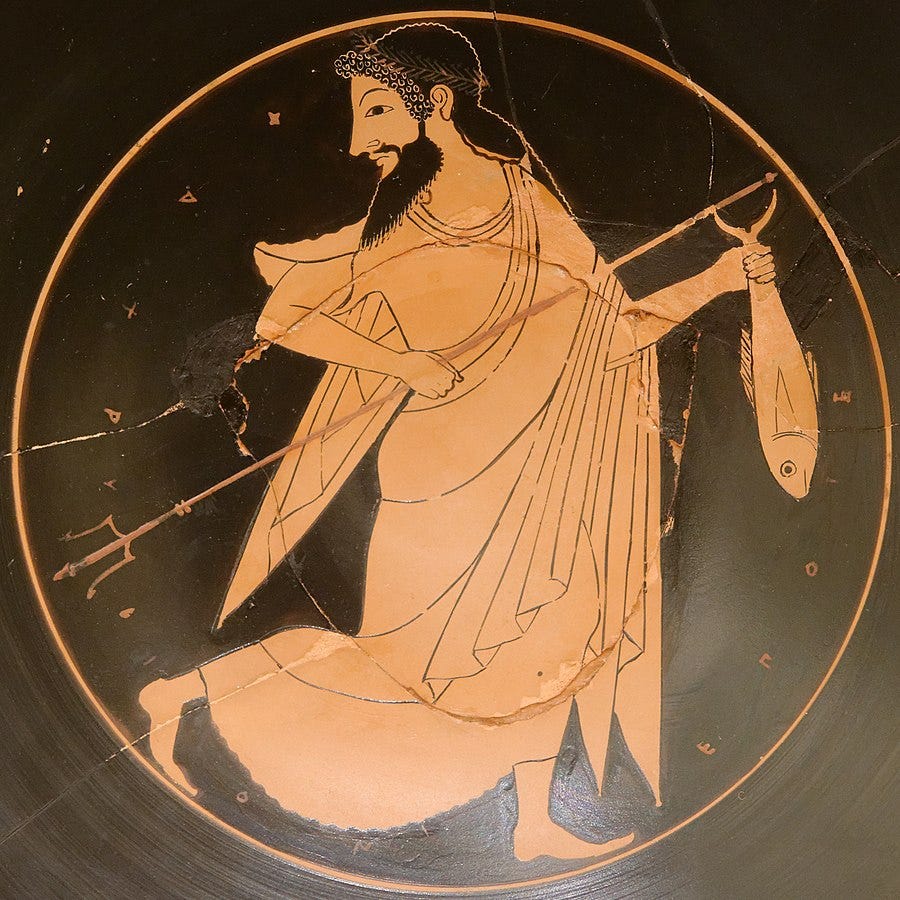

In the pantheon of Greek mythology, few deities hold as much sway over the physical and metaphysical realms as Poseidon, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes, and horses. As one of the Olympian triad alongside his brothers Zeus and Hades, Poseidon's dominion extended far beyond the waves, reaching into the earth itself with a temperamental authority that inspired both reverence and fear. His legacy endures not only in ancient literary works but also in the cultural fabric of modern society, where his traits of power, unpredictability, and the struggle for control remain strikingly relevant.

Poseidon's origins reach back to pre-Hellenic times, with his worship predating the classical Greek period. Evidence suggests that he may have originated as a local fertility or agricultural deity, linked to the earth and its creative forces. His name, derived from the Greek Posis (husband or lord) and Da (earth or land), reveals his initial ties to the terrestrial domain. It was only later, as seafaring became more central to Greek life, that Poseidon's authority shifted toward the waters. By the time the Mycenaean civilization flourished between 1600 and 1100 BCE, he had already become a major deity associated with the sea, a role confirmed by references to him in Linear B tablets as Po-se-da-o-ne.

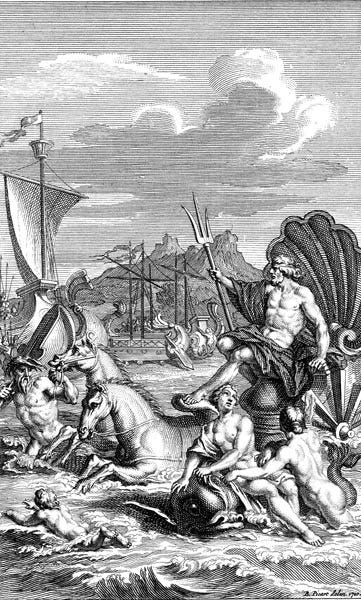

After the fall of the Mycenaean civilization, Poseidon's worship spread throughout the Greek world. Coastal cities, island settlements, and seafaring territories elevated him as their protector. Corinth, one of the major centers of his cult, built grand temples in his honor, seeking his favor for maritime trade and safe voyages. Yet Poseidon's authority was not limited to the sea. His association with earthquakes earned him the epithet "Earth-Shaker" (Ennosigaios), a chilling reminder of his power to shatter the land itself. This duality—both creator and destroyer—defined his mythology, making him a figure of reverence and terror.

Ancient literary works immortalized Poseidon's influence and character, with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey offering some of the most vivid portrayals of the sea god. In The Iliad, Poseidon is a grudging ally of the Greeks, harboring a deep resentment toward the Trojans. According to legend, Poseidon and Apollo had been forced by Zeus to build the great walls of Troy. When King Laomedon refused to pay them for their labor, Poseidon was enraged, cursing the city and vowing vengeance. This backstory colors his actions in the epic, as he defies Zeus' command to remain uninvolved and secretly aids the Greeks. His defiance reveals his rebellious streak—a powerful god unwilling to be constrained, even by the king of the gods. When he rises from the sea to rally the Greeks against Hector, his presence is as majestic as it is terrifying. The waves part, the ground quakes beneath his feet, and the battlefield trembles with divine power. In these moments, Poseidon embodies the uncontainable fury of nature, wild and unyielding.

While The Iliad showcases Poseidon's power on land, The Odyssey highlights his dominance over the sea. Here, he takes on a more personal and vengeful role, serving as the primary antagonist to Odysseus. After the hero blinds Polyphemus, Poseidon's Cyclopean son, the god unleashes his wrath, cursing Odysseus with years of wandering and suffering. It is Poseidon who stirs the sea into violent tempests, wrecking Odysseus’ ships and driving him further from home. In this role, Poseidon becomes the embodiment of divine vengeance—a relentless force that no mortal cunning can fully escape. His ceaseless punishment of Odysseus is not merely retribution; it symbolizes the chaotic, indifferent power of the sea itself, capricious and merciless.

Beyond Homer, Poseidon appears in other literary works that further define his character. In Hesiod’s Theogony, he is portrayed as one of the original Olympian gods, born of Cronus and Rhea, and second in power only to Zeus. In the tragedies of Euripides, Poseidon’s presence reveals a more sorrowful and reflective side. In The Trojan Women, he mourns the fall of Troy alongside Athena, lamenting the cruelty of war even as he acknowledges his own part in its devastation. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Poseidon takes on a more transformative role, instigating both divine punishment and miraculous change through his influence over the waters. These works collectively shape Poseidon’s literary persona—a god of immense power, whose wrath and sorrow mirror the raw, emotional forces of nature itself.

As a leader, Poseidon is both formidable and flawed. His leadership is marked by overwhelming power, yet it is often tempered by impulsiveness and pride. His authority over the sea and earthquakes makes him a symbol of chaotic strength, a ruler whose influence cannot be contained. Yet, Poseidon's rule is not without its virtues. His enduring presence in myths reflects a divine figure who persists in his aims, whether seeking vengeance or defending his domains. His unwavering pursuit of Odysseus, while ruthless, demonstrates the persistence of a leader unwilling to tolerate disrespect. Poseidon is also a god of creative force, credited with giving the first horse to humanity. His association with horses symbolizes strength and speed, making him not only a destroyer but also a giver of gifts that represent power and freedom.

However, Poseidon's leadership is also marred by destructive flaws. His impulsive wrath, as seen in his treatment of Odysseus, reflects the danger of unchecked power. His rivalry with Athena, particularly in their contest for the patronage of Athens, reveals a jealous and competitive streak. When Athena offers the olive tree to the people, a gift of peace and prosperity, Poseidon strikes the ground with his trident, creating a saltwater spring—a gesture of defiance rather than benevolence. His inability to accept defeat with grace demonstrates the fallibility of divine pride, making him a figure both awe-inspiring and tragically human.

Despite his ancient origins, Poseidon’s traits remain strikingly relatable in modern life. His volatile nature mirrors the unpredictability of human emotion and the challenges of power. In contemporary contexts, he serves as a symbol of nature’s ferocity, a reminder of the forces beyond human control. The destructive power of storms, earthquakes, and rising seas bears the mark of Poseidon, echoing the ancient belief in his temperamental dominion. His impulsive wrath, while godly, reflects familiar human struggles—jealousy, pride, and the difficulty of tempering emotion with reason. In popular culture, Poseidon is often reimagined as a conflicted figure, embodying the duality of protector and destroyer, a reflection of modern leaders whose power is both revered and feared.

Ultimately, Poseidon’s legacy is one of paradoxes—mighty and impulsive, protector and destroyer. His authority over the sea, storms, and earthquakes granted him a divine power that was as life-giving as it was catastrophic. Through Homer’s epics and other literary works, he emerges as a god whose leadership is defined by strength and flaw—a reflection of the human struggle for control over wild forces. In modern life, Poseidon’s characteristics remain relevant, symbolizing both the power and peril of unchecked authority, the consequences of pride, and the enduring influence of myth on contemporary culture. His figure continues to inspire awe, a reminder of the mercurial forces that shape both the world and the human spirit.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

The battle reaches the Greek ships, symbolizing the precariousness of their situation. What do the ships represent in the larger narrative? How does their vulnerability heighten the tension and stakes of the war?

Chapter 13 contains several vivid similes and epithets (e.g., comparing warriors to ravenous lions or waves crashing against rocks). How do these literary devices enhance the imagery and emotional intensity of the battle scenes?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 14. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Hera Outflanks Zeus and covers pages 369-386. In the Wilson translation, it is called An Afternoon Nap and covers pages 327-347.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Matthew, I always find these post fascinating. I am currently reading The Odyssey and your essays always give meaning and context to what is happening in The Odyssey. I find that wild!

In addition they are well written and full of interesting information. For example, this post gives me more context to Poseidon and his motivations. We just read the part where Odysseus blinds Polyphemus.

The first line of my translation says, “Tell me about a complicated man.” After reading your article, it makes me see that Odysseus and Poseidon are oddly enough very similar. I had not noticed that before. Both could certainly be described as complicated, and I don’t mean that in a negative way—just complex.

Thanks for sharing!

The additional background regarding Poseidon is interesting and helpful. I had no idea that Poseidon was such a prominent figure in pre-Hellenic times. The manner in which different gods take center stage at different times seems to show both the power of their emotions as well a their lack of self-control. Zeus's inattention also shows his lack of omniscience.

To me, the ships represent freewill. In the absence of ships, the Greeks have no choice but to fight. The ships provide an escape option.

I think the lion, boar and other wild animal similes throughout the Iliad are superb. They make what would otherwise be relentless gore into literature.

I was struck by the last part of this book, in which Polydamas urges Hector to pause and regroup- "less danger, more success." Hector sees the wisdom of this, but not for long. He learns of losses of vaunted commanders, and the passion of Paris and influence of Zeus bring Hector back to full battle mode. Is the failure of Hector to heed Polydamas advice meant to presage darker times ahead for the Trojans?