Exploring Life and Literature

Dear friends,

This week, I am excited to have

, share her take on the complex themes present in Cormac McCarthy's work. What I love about these personal essays is the myriad ways we can see threads of themes in various aspects of our lives.Kim lives in Mount Pleasant, SC (USA) where she is an attending neonatologist and clinical professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is married to her husband who she met when they were residents at Boston Children’s Hospital together. They have two children, neither of whom is interested in medicine: their daughter recently graduated with a double major in computer science/writing, and their son is still an undergrad in communication design. They also had guinea pigs for many years; the last one (Sir Joseph Banks) passed away in 2021 at the ripe age of 8. Kim loves to knit, play the French horn and piano, and, like many other people, started doing jigsaw puzzles in 2020. Reading has also been an integral part of her life. She loves and recommends the Bible, along with books by Ann Patchett, Edith Nesbit, AA Milne, PG Wodehouse, and CS Lewis.

They say you can tell future pediatricians by our reaction to our first time in the delivery room. A medical student who forgets there are any adults present while watching the baby transition to extrauterine life—especially if that student is officially part of the obstetric team—is destined for pediatrics.

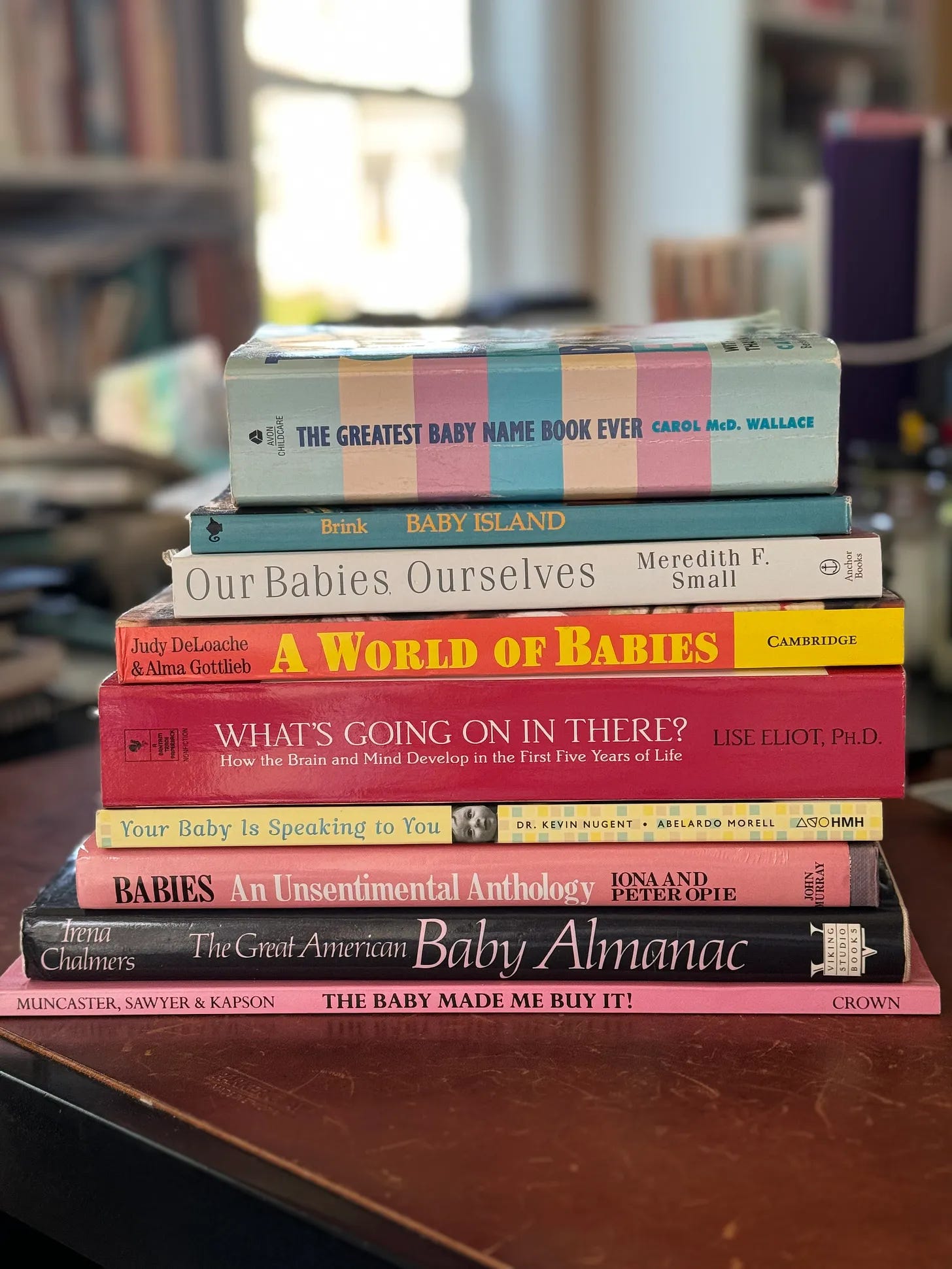

I was one of those baby-fascinated students 35 years ago, and so someone—probably a pediatric resident—took me into the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for the first time. There must have been monitors and machines beeping and flashing, not to mention vigilant, protective NICU nurses hovering. But all I remember is the vastness of the dim-dark room, filled with rows of heated transparent-walled boxes housing innumerable tiny babies under glowing lights.

Those incubators brought back memories of one of my favorite childhood places, the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We kids would cluster around the large incubator full of chicken eggs to watch crowds of hatchlings hatching. Another exhibit that fascinated me was a display of glass jars lined up on shelves, each one containing a single human embryo or fetus floating in formaldehyde, carefully arranged and suspended at progressively advancing stages of development. I don’t remember wondering much, if at all, about where they came from—what had happened to arrest their development, who their parents were, or what their parents might have felt—any more than I pondered the chicken/egg dilemma. Nor did I consciously note any difference between the warm, crowded chicks and the cold, isolated jar-babies. All these individuals, avian and human, living and dead, seemed abstract, separate, detached--not “real.”

My “real” life as a child was centered on reading. I cried on the last day of kindergarten, not because I would miss any human friends, but because I didn’t want to leave the characters (Zip and Nip) in our Weekly Reader magazines. Rows of words, sentences, and books were a refuge during a childhood punctuated by moves and mockery if not outright bullying. I apparently had to be distracted from books and words by piano lessons (which took), ballet lessons (which didn’t), and finally by limits not only on time spent reading but also on number and genre of books. "Real" books were deemed superior to fiction, and although I attempted to circumvent that requirement by frequenting the 800s in the Dewey decimal system, I gradually came to accept that the information gained from nonfiction might be more useful in the "real" world. I also got the idea that using my imagination was probably a waste of time.

Once I stopped writing my own stories, I didn’t wonder much about where books and stories came from—who the authors were, what had prompted them to write, and what they might have felt—any more than I’d wondered about the jar-babies. Nor did I wonder much about where information came from: the scientific process of asking questions and testing hypotheses seemed abstract to me as well. What seemed of utmost importance was that information, as well as facility with words, could help me solve problems, answer questions, pass tests, and eventually get into medical school—which seemed safe because it seemed to promise answers.

So there we were in the NICU, with the babies lined up in glass cases under warm lights. It would take me a few more years to realize that the abstractions and the information related to newborns--their astounding growth and development, as well as the devastating problems they can encounter in the midst of that growth and development—were the most fascinating area of medicine. I was attracted to the idea of using information about growth and development to help manage problems. I would keep reading and gathering information to make myself useful. Like Piglet with Small (short for “Very Small Beetle”) in chapter 3 of The House at Pooh Corner, I could find significance in comparison to someone even smaller. And in both cases the comparison might have been more important than the individuals.

Over many more years, I gradually discovered that the challenging thing about babies, like the rest of us, is that they (we) aren't abstractions but people. Perhaps the most fascinating thing about babies is also, arguably, the most frustrating: babies come with other people attached — in fact, when we first meet them, they are sometimes still literally attached to their moms. As pediatrician-psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott observed, “There is no such thing as a baby. There is a baby and someone."

Every baby carries a story. Their narrative is not entirely their own. Genetically and morphologically, they carry the legacy of ancestry—and epigenetically they carry the legacy of generational stress and trauma. We adults also have a tendency to attribute narratives to babies. In the NICU our patients can take on appellations like "stinker" or "troublemaker" or "fighter" depending on adults' perceptions of their medical challenges. We also will take upon ourselves the blame for "breaking babies" if we happen to be around when a baby's course takes a turn for the worse.

Since that first delivery room experience, I’ve had the privilege of seeing thousands of newborns "transition" to life as a separate entity—yet they are not truly separate. Newborns are helpless on their own, even when they don’t need critical care. And something about helpless babies seems to bring out fear and uncertainty and an isolation-impulse in most of us adults.

In the NICU we commonly refer to incubators as "isolettes": a brand-name thing, like Kleenex or Jell-O. And that sense of isolation and distancing is strong in the NICU. Parents are often afraid to touch their babies even after the careful regimen of handwashing on every arrival/entry to the unit. “Popping the top” on the incubator, when a baby is large enough and old enough to try staying warm without full support, is a huge milestone. But picking up and holding the baby—even knowing that touch is crucial to infant development—can still be scary.

Tiny, fragile premature babies evoke fear—but larger, older, vigorous babies may as well. Adults can fear not just the babies that fit in the palm of a hand—although those are plenty scary—but the large ones, the crying ones, the dying ones. The fears come in different flavors: fear of breaking them, fear of getting something wrong, fear of not being able to protect them because we can’t predict what will happen.

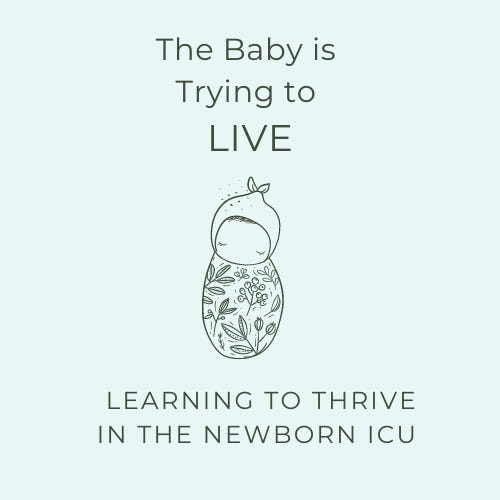

I wonder if the varied flavors of baby-fear all boil down to a fear of the helplessness we all still carry, because babies relentlessly remind us of that helplessness. Especially the ones who land in a NICU, because their helplessness goes beyond baseline baby-helplessness.

But what if being helpless is not the same as being abandoned or alone? What if we might be more like the baby chicks huddled together than the jar-babies lined up in their artificially-imposed individuality? What if, paradoxically, admitting our limits helps us connect?

All of us will be confronted by our own limits and helplessness; we don’t need a NICU for that.

True, those of us who work with critically ill newborns have gained information and knowledge from years, decades, even centuries of collectively watching and studying babies' development and physiology. We’re constantly discovering more ways we can support our patients when things go awry. But we still run up against gaps and cracks, far more often than we’d like: situations in which the knowledge doesn’t translate to power, or at least not to the power that can fix a broken situation.

At those times when a baby can’t survive without more "fixing" than even the highest-level critical care can offer, we adults are the ones who often feel helpless. We may also identify a sense of moral distress when we are confronted with babies whose prognosis is uncertain: they are too early, or too complicated/compromised, for us to tell their families whether they will survive and what their future might contain.

I think that kind of distress has to do with our expectations. As adults, we tend to want the certainty of knowledge and information. Babies, on the other hand, rely on the certainty of presence and relationship.

When we allow ourselves to sit, helpless, with the babies, we gradually discover that what we have left—words and presence—constitute a different kind of power: the power that can transform us from mere voyeurs of grief to active witnesses of life and love.

Bearing witness and carrying with-ness are not the same as fixing: they are healing. And healing is more challenging than “fixing” or “helping” because healing first requires not “overcoming” fear and uncertainty, but admitting to all of it.

What if uncertainty doesn’t have to lead us only to distress? What if we could learn to see these feelings of distress as opportunities to "pop the top”—to tell our stories, to bring beauty from suffering by bearing witness to live and love?

Telling our stories can move us away from staring at the jars and peering into the boxes toward making connections. Even though the process means vulnerability, without opening —“popping the top”—there’s no possibility of being held. And what we babies need is not certainty of predicted outcomes but company, faithfulness, presence.

What if we adults, in these deepest needs, are no different from the babies?

What if we can and should take refuge in books, not because they let us hide from trouble and uncertainty, but because they connect us? Books—like babies—come from people, carry their stories, and allow us to see ourselves in them. Words are a gift of connection. They allow us not only to produce and ship and preach and teach, but also to relate. Because, together, we are all in the process of becoming complicated, nuanced, narrative-layered people: slowly, gradually, over time.

We have met the babies, and they are us.

You can check out more of Kim’s writing at her publication.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you have the means and desire, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Until next time…

Katrina, thank you so much for reading and for your kindness!

Kim’s insight into the NICU experience, particularly her observation that “babies come with other people attached,” beautifully captures the interconnectedness of humanity. This essay thoughtfully bridges the clinical world and personal reflections, making it very moving. Her eloquence and empathy draw readers into the complexities of vulnerability, connection, and shared stories.