Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular essays appear on Tuesdays and Book Club essays on Fridays.*

"And the dark came swirling down across his eyes."

Dear friends,

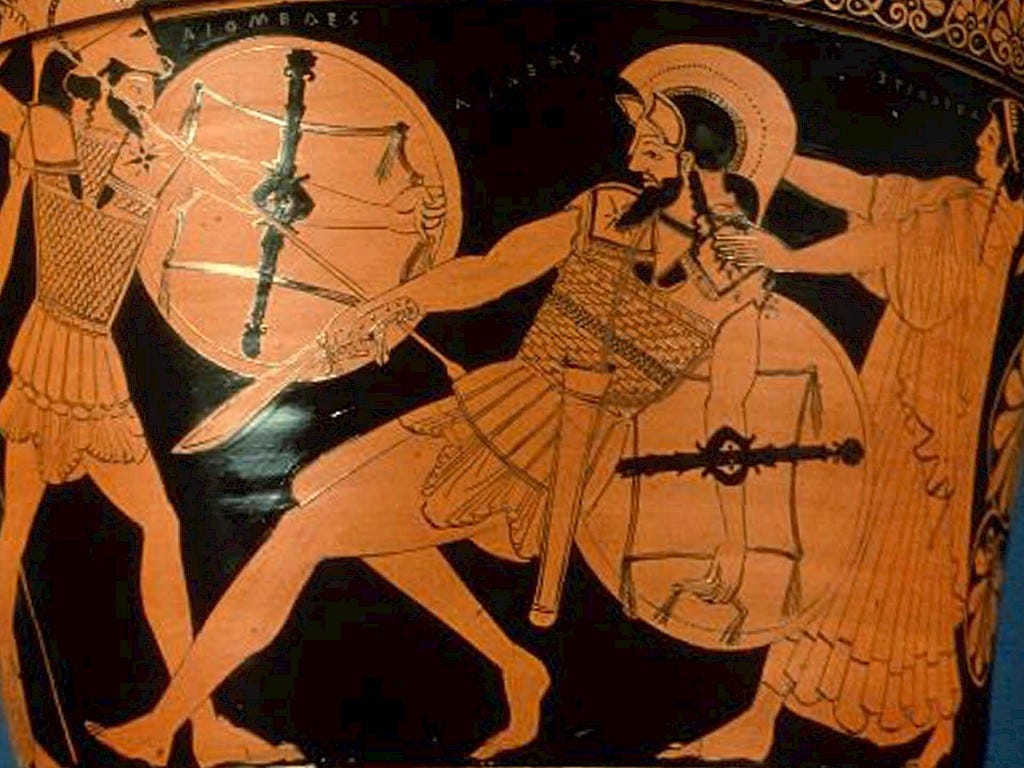

In Book 5, Diomedes Fights the Gods, Homer vividly portrays heroism, divine intervention, and the tenuous boundary between mortal and immortal realms. This book centers on the Achaean hero Diomedes, whose courage and strength, amplified by divine assistance, allow him to dominate the battlefield and even challenge the gods. The narrative unfolds as an intricate interplay of mortal valor and divine power, showcasing Homer’s ability to intertwine human ambition and divine influence.

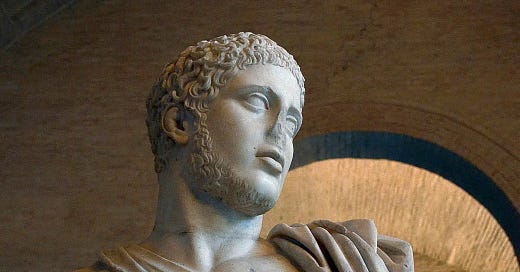

The book begins with the goddess Athena granting Diomedes extraordinary strength and courage. Responding to his prayer for aid, she invigorates and bestows upon him the ability to discern gods on the battlefield. This divine gift underscores Diomedes’ unique role as a hero chosen by the gods, though it also carries significant risks. Empowered by Athena, Diomedes embarks on a ferocious rampage, slaying numerous Trojan warriors, including Phegeus and his brother Idaios. His unparalleled ferocity on the battlefield marks the onset of his aristeia, or his finest moment in battle, a recurring motif in Homeric epics.

The narrative takes a dramatic turn with the involvement of Aphrodite. When Aeneas, the Trojan prince and son of Aphrodite, faces mortal peril in combat with Diomedes, the goddess descends to the battlefield to save her son. Diomedes wounds Aphrodite on her wrist in a daring and unprecedented act, forcing her to retreat to Olympus in shame. This moment is striking for its audacity: a mortal injuring an immortal shatters the presumed invulnerability of the gods and underscores the theme of human agency within the divine order. Zeus’ reproach compounds Aphrodite’s humiliation as he scolds her for meddling in a domain—war—beyond her purview.

As Aphrodite exits the fray, Apollo steps in to rescue Aeneas, enveloping him in a protective mist and whisking him to safety. Apollo’s intervention restores balance but highlights the gods’ partiality and willingness to tilt the scales in favor of their chosen mortals. The battle escalates further when Apollo summons Ares, the god of war, to inspire the Trojans. With Ares’ presence, the Trojans regain their momentum, shifting the tide of the conflict.

In a climactic encounter, Diomedes confronts Ares himself, emboldened by Athena’s continued support. Athena, serving as his charioteer, guides Diomedes as he hurls his spear and strikes the god of war, wounding him deeply. Ares’ bellow of pain reverberates across the battlefield, causing terror among both armies. Defeated, Ares retreats to Olympus, where he complains to Zeus about Athena’s role in his injury. However, Zeus shows little sympathy, chastising Ares for his recklessness and destructive tendencies. This interaction underscores Zeus’ complex role as the arbiter of divine and mortal conflicts, revealing his disapproval of unchecked divine interference in human affairs.

Homer masterfully balances the dynamics of mortal combat and divine intervention throughout this book. Far from being impartial observers, the gods are deeply invested in the war's outcome, often acting out of personal grudges or favoritism. Diomedes’ ability to challenge and wound the gods raises compelling questions about the power dynamics in the epic. Is Diomedes’ success purely the result of divine favor, or does it also reflect an intrinsic human potential to transcend mortal limitations? This theme resonates throughout The Iliad, highlighting the fragile and shifting boundaries between mortals and immortals.

This book also serves as a testament to Diomedes’ heroism. His bravery, strength, and willingness to defy even the gods establish him as a quintessential Achaean hero. The temporary divine insight he receives from Athena elevates his status and underscores the precarious nature of human reliance on the gods. Diomedes’ actions exemplify the Homeric ideal of heroism, where personal glory and divine favor are inextricably linked.

The proliferation of names in this chapter, often referred to as the "catalog of the slain," serves multiple purposes, both narrative and thematic. While Diomedes is undoubtedly the central figure of this book, including the names of numerous other characters—many of whom are killed in his aristeia—contributes to the richness and complexity of the epic.

One of the primary purposes of naming the slain is to give them a form of immortality. By including their names, Homer ensures that these warriors, no matter how minor their roles in the narrative, are remembered. In a society that highly valued kleos (glory or renown), even a brief mention in the epic grants eternal recognition. These names might have resonated with Homer’s audience, who could have recognized them as local or ancestral heroes. Diomedes kills Phegeus and Idaios early in his aristeia. While these characters play no major role in the larger narrative, their deaths are recorded with a degree of respect and detail, underscoring their bravery in facing such a formidable opponent.

The sheer number of names underscores the vastness of the conflict. This is not a duel between a few select heroes, but a clash involving thousands. By listing individual combatants, Homer highlights the breadth of the Trojan War and the many lives it consumes. The enumeration of names adds a layer of realism to the narrative, reminding the audience that each warrior—whether Achaean or Trojan—is a person with a life and a story, tragically cut short by the violence of war.

The litany of names also enhances Diomedes’ reputation. His ability to defeat so many warriors in a single day underscores the extraordinary nature of his aristeia. The accumulation of victories builds momentum, elevating Diomedes from a strong warrior to a near-mythic figure of martial prowess. Each name adds weight to Diomedes’ achievements, making his rampage feel monumental. The sequence also reinforces that his feats are divinely aided, as no mortal could otherwise accomplish such dominance.

Homer’s detailed naming contrasts the fallen's individuality and the collective experience of war. Each name reminds us that these are not faceless soldiers, but distinct individuals with histories and families. This contrast heightens the tragedy of war, as it transforms personal lives into anonymous casualties of a larger conflict. The names of minor warriors, juxtaposed with those of more prominent figures like Aeneas, illustrate the democratic nature of death in war—it spares neither the great nor the small.

The catalog of names and deaths also serves a structural purpose, providing a rhythmic progression to the narrative. The repetition of names and brief descriptions of their deaths creates a sense of inevitability, leading up to the more climactic moments of the chapter, such as Diomedes’ confrontations with Aphrodite and Ares. The alternation between rapid, almost list-like recounting of deaths and the more dramatic, drawn-out scenes (such as Aeneas’ near-death) keeps the audience engaged and mirrors the chaos of the battlefield.

The naming of many characters, even minor ones, is also a hallmark of the oral tradition in which Homeric epics were composed. Lists of names would have been mnemonic aids for oral poets, helping them structure the narrative and transition between episodes. These names also allowed performers to localize the story, inserting names recognizable to a particular audience. By naming so many warriors, Homer reminds the audience of the interconnectedness of human lives and the far-reaching consequences of war. Each death ripples outward, affecting families, communities, and future generations. This attention to individual warriors reflects the epic’s broader themes of fate, mortality, and the price of glory.

Diomedes Fights the Gods encapsulates the central themes of The Iliad: the interplay of human and divine, the pursuit of glory, and the ever-present influence of fate. Through Diomedes’ extraordinary exploits, Homer invites readers to explore the tensions and synergies between mortal ambition and divine will. This book celebrates the hero’s courage and reflects on the larger forces shaping the Trojan War, making it a pivotal chapter in this timeless epic.

"Pallas Athena set the man ablaze, his shield and helmet flaming with tireless fire like the star that flames at harvest, bathed in ocean, rising up to outshine all other stars— so bright the fire flared from his head and shoulders, blazing as Athena drove him into the center."

The concept of aristeia is a key element in ancient epic poetry, particularly in The Iliad. Derived from the Achaean word aristos, meaning "best" or "excellent," aristeia refers to a hero’s finest moment in battle—a display of extraordinary valor, skill, and success. This literary device highlights the hero’s prowess and elevates them as exemplary figures within the narrative. In many ways, an aristeia is both a showcase of the hero’s potential and a narrative peak that underscores the grandeur and tragedy of war.

An aristeia typically follows a structured pattern:

Divine Inspiration: The hero often receives assistance or favor from a god or goddess, enhancing their abilities and courage.

Preparation for Battle: The narrative might focus on the hero arming themselves, emphasizing their readiness.

Domination on the Battlefield: The hero achieves a series of remarkable victories, sometimes described in graphic detail, demonstrating their supremacy.

A Pivotal Moment: The hero confronts and defeats a significant opponent or performs a superhuman feat.

Divine Opposition: The gods may intervene, either to aid the hero further or to halt their rampage, preventing a complete rout.

Purpose in the Narrative: Aristeia serves multiple purposes:

It glorifies the hero, solidifying their reputation and legacy.

It creates dramatic tension by depicting the heights of human achievement and its inevitable limitations.

It illustrates the interplay between human effort and divine influence, a central theme in Homeric epics.

Throughout our time in The Iliad, the aristeia will play an important recurring role. In addition to this instance for Diomedes there will be sections devoted to Hector, Patroclus, and Achilles, each detailing their critical role in this epic tale. However, the aristeia is not limited to The Iliad; it appears in other epic traditions including The Odyssey, when moments of individual excellence can be likened to aristeia, such as Odysseus’ triumphs in physical challenges or his strategic cunning. Also, in the Roman tradition, Virgil’s Aeneid includes aristeia-like moments, such as Aeneas’ feats in battle during the war in Italy.

The aristeia is used by ancient writers to focus on significant themes including:

Mortality and Glory: Aristeia underscores the heroic pursuit of kleos (glory) and time (honor). While heroes achieve extraordinary feats, their victories often come at great personal or communal cost, reinforcing the bittersweet nature of war.

Interplay of Divine and Mortal: Aristeia highlights the tension between human effort and divine intervention. While the gods elevate the hero, they also remind mortals of their dependence on divine favor.

The Fragility of Human Greatness: Aristeia is often fleeting. Just as the hero reaches their zenith, they may encounter setbacks or death, reflecting the transient nature of human achievement.

Aristeia is a cornerstone of epic storytelling, serving as both a celebration of human potential and a meditation on its limits. In The Iliad, these moments are not just displays of martial prowess but also windows into the larger existential struggles of honor, mortality, and fate. Exploring the aristeia of various heroes—Diomedes, Hector, Patroclus, and Achilles—offers rich insights into Homer’s vision of heroism and its costs. These episodes continue to resonate, showcasing the timeless allure of heroism in the face of inevitable mortality.

As I read this week’s chapter a few different things popped out to me that I thought I would highlight. Let me know your thoughts on these or any others that spoke to you.

How does Diomedes embody the characteristics of a Homeric hero in this book?

How does Homer build suspense and drama during Diomedes' heroic rampage?

Athena emboldens Diomedes to wound Aphrodite and later challenges Ares. Is his willingness to defy the gods an act of heroism or hubris?

Homer uses vivid and often gruesome imagery to describe the battle scenes. How does it enhance your understanding of the chaos and brutality of war?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 6. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Hector Returns to Troy and covers pages 195-213. In the Wilson translation, it is called The Price of Honor and covers pages 133-154.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Firstly, I love the images you include in your essays. The way that visual art and literature interact and inform our understanding of each is always really interesting.

How we perceive various characters in literature is informed by how society depicts them. There is a good analysis of the evolution of Helen’s character through the ages in Bettany Hughes’ book on her - which I highly recommend for archeological background on the Iliad etc.

In relation to heroism vs hubris - I am not sure that a lot of the time there is a difference. I think that for heroism not to have an element of hubris it needs to be private and not in seeking honor or glory - so it would be hard to find in the epics.

I still struggle with the “god(ess) made me do it” excuse/ reason which pervades the Iliad - when others and not the hero have to bear the burden of the consequences of the hero’s actions. But that applies to more than just the Iliad.

The fact that Homer named so many insignificant players throughout the epic is something that struck me in this chapter, too, for the same reasons. Even though this war is huge, reading these names was a stark reminder of how individual it truly is. He even gives some context to some of their deaths, like who they left behind and mourned for them.

Interestingly, I didn't read Diomedes as heroic this time around, even though he's clearly intended to be interpreted as such. Maybe it was the framing of how he attacked Aphrodite as she was trying to protect her son. That rather made my blood boil. After that, it coloured all his other slaughters.