Exploring Life through the Written Word

“Never bury my bones apart from yours, Achilles, let them lie together.” – Patroclus’ spirit to Achilles

Dear friends,

Book 23 of Homer’s The Iliad, translated by Robert Fagles, opens with the grief of Achilles as he mourns the death of his closest companion, Patroclus. Following the dramatic and violent death of Hector in Book 22, this chapter marks a tonal shift from wrathful vengeance to sorrow, commemoration, and the reintegration of communal ritual. Achilles, though still wrapped in the armor of violence, begins to move toward healing through mourning and ritual acts. Book 23 is centered around the funeral of Patroclus, culminating in a series of elaborate funeral games held in his honor.

The book opens with Achilles unable to sleep, haunted by grief. He cradles the body of Patroclus and weeps, calling upon his friend's ghost to visit him. In a moment of deeply personal emotion, Patroclus' spirit does indeed appear to Achilles in a dream. The ghost begs for burial, unable to cross into the land of the dead until his body is properly committed to the earth. Achilles promises to carry out the funeral rites, including a pyre and a mound, and pledges that their bones will rest together once Achilles himself dies.

With dawn, Achilles rouses his comrades to build the pyre. Wood is gathered from the forests, and the body of Patroclus is washed, anointed, and laid upon the pyre. Achilles sacrifices animals—including horses, dogs, and Trojan captives—as part of the funerary rite, a stark and brutal reflection of the honor culture of Homeric warfare. He places locks of his own hair on the body as a final token of grief and cuts them as an offering, a symbolic gesture of personal loss and transformation. As the pyre burns, Achilles prays to the winds Boreas and Zephyrus to fan the flames, showing his continued command over divine forces. The flames consume the body, and Achilles paces, sleepless and restless, until the dawn.

Afterward, the ashes of Patroclus are collected and sealed in a golden urn provided by the god Hephaestus. Achilles places them in his tent for temporary safekeeping, until they can be mingled with his own remains. A burial mound is planned, but the full structure is deferred until after Achilles' death, further foreshadowing his impending fate.

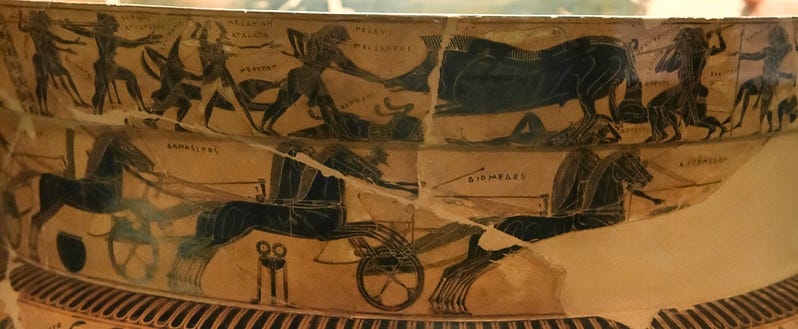

In the second half of the book, Achilles announces funeral games in honor of Patroclus, providing a temporary reprieve from the bloodshed of war. The games include a chariot race, a boxing match, wrestling, a footrace, a duel in arms, discus throwing, archery, and spear-throwing. Each contest is a chance to win prizes, gain fame, and demonstrate excellence. The narrative becomes a series of vignettes focused on the various Greek warriors who participate in each event.

The chariot race is the most extended and dramatic of the contests. Diomedes, with the aid of Athena, wins first place. Antilochus, the son of Nestor, uses clever maneuvering to take second, while Menelaus contests Antilochus' aggressive tactics, resulting in a dispute that is resolved through diplomacy. Achilles awards prizes with fairness, reinforcing his role as judge and reconciler.

The other contests follow in quick succession: Epeius wins the boxing match with brute force; Odysseus, aided again by Athena, wins the footrace; Ajax and Odysseus wrestle to a draw; and Achilles awards various honors and prizes in recognition of bravery and merit. In each event, Achilles plays the role of host and arbiter, presiding over competitions that both commemorate Patroclus and restore a sense of order and fraternity among the Achaeans.

The book closes not on violence, but on community, athleticism, and the intricate rituals that mark transitions: from life to death, from wrath to grief, from isolation to reintegration. It is a chapter of mourning, honor, and symbolic reconciliation.

Book 23 of The Iliad stands as a meditative pause in the epic’s relentless tide of war. After the brutal climax of Hector’s death in Book 22 and before the final confrontations of Book 24, this chapter offers a reflection on grief, commemoration, and community. Through its elegiac tone and structured games, it explores themes of mortality, honor, and the healing power of ritual.

Achilles, who has become almost inhuman in his grief-driven rage, begins to return to a form of human fellowship in this book. His lamentation over Patroclus is not merely emotional; it is deeply ritualistic. By washing and anointing the body, sacrificing captives and animals, and calling on the winds to fan the pyre, Achilles performs an intricate rite of passage for the dead. These actions mark the transformation of Patroclus from fallen warrior to honored ancestor.

The interaction between Achilles and the ghost of Patroclus is one of the most emotionally resonant moments in the epic. Achilles, who until now has scorned custom, even refusing food and rest, is moved to fulfill the demands of the underworld. The Homeric vision of the afterlife requires proper burial, or else the spirit cannot rest. This scene illustrates a core cultural belief: death is not merely an ending, but a transition that demands observance. Achilles' gradual submission to ritual reveals his reentry into the human world and foreshadows his eventual acceptance of his own mortality.

The funeral games are more than athletic contests—they are acts of collective catharsis. In a world dominated by conflict, these games serve a restorative function. The same men who have fought beside and against one another now compete in a framework of order, not violence. The contests serve multiple purposes: they honor the dead, they affirm the living, and they create a space for glory that is not dependent on killing.

In literary terms, Homer uses the games to showcase individual characters and their traits. Odysseus’ cunning, Diomedes’ strength, Antilochus’ ambition, and Menelaus’ dignity all come to the fore. These moments of character development enrich the epic and allow a temporary reorientation of values. Victory is achieved not through destruction but through excellence (aretê) and honor (timê).

Achilles' role here is significant. He is not a competitor but a judge and benefactor, suggesting a subtle shift in his character. The man who could not be placated after the loss of Briseis now gives prizes freely, showing generosity, fairness, and even humor. His reconciliation with the Achaean leaders is implied rather than stated outright. Through the shared ritual of the games, the warriors find a sense of unity and purpose that war alone cannot provide.

Death looms over the entirety of Book 23. Patroclus is honored because he has died, but also because he represents Achilles' own fate. When Achilles places a lock of his hair on the pyre, it is both a gift and a sign of farewell—not just to Patroclus, but to his own youth and innocence. He has entered a liminal space where his death is imminent, yet still deferred. By promising that their bones will be mingled, Achilles symbolically binds his own future to the legacy of Patroclus.

The funeral rites serve as a form of narrative closure for Patroclus and a premonition of Achilles’ own end. The text offers no false comfort. Death is final, but legacy—honor, memory, friendship—endures. The ashes in the urn become a metaphor for the fusion of two lives shaped by love and war. It is one of Homer’s most poignant statements about mortality.

Despite the archaic context of chariot races and animal sacrifices, the central themes of Book 23 remain deeply resonant. At its heart, this book is about how we mourn, how we remember, and how we find meaning in the face of death.

Modern societies still rely on ritual to navigate loss. Funerals, wakes, memorial services, and even athletic events in honor of the departed reflect a universal human need to process death communally. Achilles’ careful orchestration of the funeral and games mirrors the way modern communities gather to honor loved ones—with speeches, tributes, and commemorations that channel grief into meaning.

Achilles’ transition from vengeance to mourning also mirrors the psychological journey of grief. Initially consumed by rage, he gradually reclaims a sense of self and community through ritual. This psychological arc is mirrored in the experiences of those who lose loved ones in the chaos of war, accident, or illness. Grief isolates, but ritual heals.

The funeral games speak to our enduring impulse to remember the dead through acts of excellence and celebration. In the modern world, we see echoes of this in charitable foundations set up in someone’s name, sporting events dedicated to fallen athletes, or artistic tributes to the deceased. These acts are not merely symbolic—they serve as living reminders that a life mattered and that their legacy persists.

The communal dimension of Book 23 also reflects the importance of solidarity in times of hardship. As in Achilles’ case, mourning is not a solitary act. The Achaean leaders rally together to participate in the games, affirming bonds of loyalty and friendship. In modern life, whether in military funerals, memorial marathons, or community vigils, collective expressions of grief reinforce social cohesion.

Achilles’ acknowledgment of his own mortality is perhaps the most haunting aspect of the book. He knows he is fated to die, and yet he finds meaning in that knowledge. His choice to honor Patroclus becomes an act of self-recognition. In our contemporary lives, grappling with the reality of death often clarifies values, deepens relationships, and compels us to act with intention.

This is not unique to soldiers or ancient heroes. The awareness of mortality is part of what makes us human. From terminal diagnoses to personal losses, the confrontation with death often leads to deeper reflection, greater empathy, and acts of beauty—whether in writing, sport, or ritual.

Book 23 of The Iliad is a masterful exploration of grief, memory, and the slow return to humanity after the dehumanizing force of rage. It is a chapter where Achilles, the fiercest of warriors, reveals the tender core of his identity—not as a killer, but as a mourner, a friend, and ultimately, a man who knows he too will die.

Through the rituals of burial and the structure of the games, Homer offers a space for healing and remembrance. The themes of Book 23—honoring the dead, competing with integrity, mourning with ritual, and preparing for one’s own end—are not relics of a vanished past. They are enduring truths that speak to the universal human condition.

In its deep humanity, Book 23 bridges the ancient and the modern. Achilles’ grief is our grief. His search for meaning in death echoes in our funerals, our memorials, and our lives. And in the communal rites that follow loss, we, like the Achaeans, find a path back to the living.

In the grand tapestry of the Trojan War—a tale of divine rage, martial glory, and doomed love—few figures evoke as much pathos as Priam, the last king of Troy. Unlike the fierce warriors or scheming gods who dominate the epic landscape of The Iliad, Priam is a man weighed down not by the burden of ambition but by the agonies of age, loss, and moral dignity. He is the human face of a city on the brink of ruin.

In this essay, we will explore Priam’s mythological origins, his role in ancient literary works, and the cultural context that shaped his identity. We will analyze the enduring qualities of Priam’s character—his piety, eloquence, and tragic nobility—and consider how these traits make him a deeply relatable figure across the centuries.

Mythological and Historical Origins

Priam (Greek: Πρίαμος, Priamos) is known in Greek mythology as the last king of Troy during the Trojan War. According to myth, he was born to King Laomedon of Troy, who was notorious for cheating the gods Apollo and Poseidon after they built the city’s walls. In retaliation, Heracles attacked Troy and killed Laomedon and his sons—except for Priam, who was spared and later restored to the throne.

The name “Priam” is possibly derived from the Luwian (Anatolian) root Pariyamuwa, which may be linked to local royal titles, suggesting his character could have had some loose historical or folk basis in Bronze Age Anatolia. This linguistic theory lends some plausibility to the notion that Priam may have originated from an oral tradition combining historical memory with mythological embellishment.

Historically, Troy was believed to have been a real city located in what is now Hisarlik, Turkey. Archaeological excavations have revealed multiple layers of settlement, with Troy VIIa commonly identified as the level destroyed around 1200 BCE—the likely historical context for the mythologized Trojan War. While there is no evidence for a king named Priam, the existence of a powerful ruler overseeing a wealthy, strategic city in this period is plausible.

Priam thus stands at the intersection of myth and history. He represents not just a legendary monarch but a memory of a civilization undone by forces larger than itself—be they Greek armies or Homeric fate.

Priam in The Iliad

Priam’s most enduring literary presence is in Homer’s Iliad, particularly in its later books. While he is referenced earlier as the ruler of Troy and father of many sons—most notably Hector, Paris, and Helenus—his most striking appearance comes in Book 24, where he journeys into the enemy camp to ransom the body of Hector from Achilles.

Throughout The Iliad, Priam is depicted as a figure of authority and wisdom, though often impotent in the face of fate. His age, symbolic of a long-reigning monarch, stands in contrast to the youth and vitality of the warriors around him. When Hector proposes to confront Achilles, Priam pleads with him to reconsider, saying:

“I beg you, dear child, think—don’t pit yourself against that man, alone, without a friend!” (Iliad 22.47, Fagles translation)

These are not the words of a king commanding his armies but of a father terrified of losing his son. It is this duality—king and father, authority and impotence—that defines Priam’s literary role.

In Book 24, Priam undertakes what is perhaps the most emotionally powerful journey in all of Homer. Accompanied by Hermes, who guides him safely through the Greek camp, the aged king enters the tent of Achilles and falls to his knees, grasping the hands of the man who killed his son. He speaks not as a king but as a grieving father:

“I have endured what no one on earth has ever done before—

I put to my lips the hands of the man who killed my son.”

(Iliad 24.588–589)

This act of humility and courage breaks Achilles’ hardened heart. The wrath that has consumed him since Patroclus’ death begins to dissolve. In this moment, Priam becomes more than a Trojan king—he becomes a universal symbol of grief, mercy, and the dignity of the human condition.

Priam in Other Ancient Texts

Priam’s story is not confined to The Iliad. He appears in various other sources, both Greek and Roman, which expand or reinterpret his narrative.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, Book II offers a harrowing depiction of Priam’s death during the sack of Troy. As the Greeks storm the city, Priam attempts to don his old armor and defend his palace. He witnesses the brutal murder of his son Polites by Neoptolemus (the son of Achilles) and is himself slain at the altar of Zeus.

“Thus Priam fell, and Troy’s great age was ended.”

(Aeneid 2.557)

Where Homer gives Priam a dignified moment of peace in The Iliad, Virgil emphasizes his helplessness and the brutality of war. The scene marks the collapse of the old order and the fall of a civilization. It also reinforces Priam’s tragic status—a man who survives to see his kingdom destroyed and his children slaughtered.

Priam also appears in the Epic Cycle—a collection of now-lost poems that include the Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Troy—as well as in the post-Homeric works of tragedians like Euripides and later Roman writers. Each version preserves the essential qualities of Priam: his nobility, his grief, and his helplessness in the face of destiny.

Priam as a Symbol: Father, King, and Human

What makes Priam a figure of enduring power is not his military prowess or political ambition, but his deeply human qualities. In a narrative dominated by warriors and gods, he stands out as a figure of vulnerability, empathy, and moral integrity.

Priam’s identity is inseparable from his role as a father. He is father to fifty sons and many daughters, but it is Hector who represents the pride and future of Troy. Hector is not only Troy’s greatest warrior but Priam’s heir, the embodiment of the city's honor and strength.

When Hector dies, Priam's grief is overwhelming not just because of personal loss, but because it marks the symbolic death of Troy itself. In begging Achilles for Hector’s body, Priam channels every parent who has outlived a child, every person who has begged for justice or mercy in the face of devastation.

This dimension of Priam’s character transcends time and place. In the modern world—racked by war, loss, and displacement—images of grieving parents persist in media coverage of conflict zones, refugee crises, and senseless violence. Priam speaks for all who mourn loved ones in circumstances beyond their control.

Though largely powerless in the military affairs of the war, Priam remains a moral center in The Iliad. His palace is a place of prayer and tradition, and his words carry the weight of reason in a time of chaos. His authority comes not from the sword but from wisdom and compassion.

In Book 3, when Helen is summoned to view the duel between Paris and Menelaus, Priam speaks to her with gentleness and dignity, expressing no blame for her role in the war. This moral clarity stands in contrast to the impulsiveness of Paris and the brutality of war.

In a modern political context, Priam evokes the ideal of the statesman—one who leads not through dominance but through principle. He is the elderly leader whose voice is tempered by experience, who sees the futility of war even as others rush into it.

Priam is ultimately a tragic figure. His fate is not the result of personal hubris or divine punishment but of circumstances beyond his control. He is born into a doomed city, fated to watch it fall. He represents a civilization at its twilight.

In this sense, Priam resonates with characters like King Lear or Oedipus—a man of stature who endures profound suffering. His tragedy is made more poignant by the grace with which he accepts it. Even when everything is lost, he holds to dignity, to ritual, to language. In doing so, he preserves his humanity.

Despite his mythological origins, Priam is a profoundly modern figure. His experiences—grieving the loss of a child, trying to maintain moral integrity amid violence, watching the collapse of a society—mirror many contemporary struggles.

In an era of ongoing war, mass displacement, and generational trauma, Priam’s grief speaks with renewed urgency. Parents in Gaza, Ukraine, Syria, or Sudan echo Priam’s pleas for the return of their dead. The image of an elderly man kneeling before his enemy to reclaim his child is not ancient history—it is today’s news.

His grief is not performative or politicized; it is deeply personal. That emotional core makes him an icon of human endurance.

Modern leadership often prioritizes power, strategy, or populism. Priam reminds us that leadership can also mean mourning with the people, standing for tradition, and acting with dignity in the face of defeat. His refusal to surrender to hate—even when confronting Achilles—models a form of leadership rooted in reconciliation.

In the context of post-conflict societies or divided nations, Priam’s example urges a turn away from vengeance and toward mutual recognition of suffering.

Finally, Priam’s story raises ethical questions that are still with us: How should the victors of war treat the vanquished? What obligations do the powerful have toward the powerless? Is there space for mercy in a world ruled by ambition?

Achilles is moved not by strategy but by Priam’s humanity. In showing us this transformation, Homer suggests that empathy, even in war, is possible—and essential.

Priam of Troy is not remembered for his battles or conquests, but for his courage in mourning, his steadfast morality, and his ability to act with grace amid devastation. He is the embodiment of what it means to lose everything and still remain human.

Through Homer, Virgil, and other classical texts, Priam stands as a mirror to our own age—an age that continues to struggle with war, grief, and the search for dignity in suffering. His story, though ancient, is not alien. It belongs to anyone who has wept for a child, who has tried to lead with wisdom, who has witnessed the end of an era.

In the end, Priam reminds us that the measure of a man is not how he rules in power, but how he kneels in sorrow—and how, even in that posture, he affirms the enduring nobility of the human spirit.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

How does Achilles role as mourner and host of the funeral games contrast with the rage-filled warrior we saw earlier? Do you view this as a redemptive moment?

In what ways do the funeral games honor Patroclus, and what might they say about ancient Greek values such as aretê (excellence) and timê (honor)?

How does the bond between Achilles and Patroclus deepen our understanding of grief, love, and legacy in The Iliad? What modern parallels can you draw?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 24. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Achilles and Priam and covers pages 588-614. In the Wilson translation, it is called A Time to Mourn and covers pages 581-610.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

The descriptions of the conduct and reactions of the game contestants are some of the most humanizing passages we've encountered in the Iliad. It is interesting that competitive games are a key feature of the rituals to honor the dead. The games seem to be a way for mourners to replace their sorrow with the emotions that arise from competing in sporting events or cheering a favored contestant. The games, at the very least, offer a respite from anguish and grief over the death of the loved one.

Matthew, I've just finished Book 24, the last book of The Iliad. Reading your excellent note on Book 23 I am struck by the parallels and contrasts between Achilles's mourning for Patroclus in Book 23 and Priam's mourning for Hector in Book 24. Maybe you're going to speak to that in your note on the latter.

Since I have finished a little bit ahead of the group's schedule I am going back and re-reading Bernard Knox's Introduction to better understand and appreciate his commentary.