Homeward Bound - An Introduction to The Odyssey

Introducing The Odyssey

Exploring Life through the Written Word

“The Odyssey is centrally about displacement, transformation, and recognition. It asks what it means to be a person at all, when everything that gives you identity has been stripped away.” —Emily Wilson, Introduction to The Odyssey

Dear friends,

The smoke of Troy has scarcely cleared. Achilles is dead. Hector’s body has been ransomed. Priam has returned to a shattered city. The heroes of The Iliad—gods-touched, honor-bound, tragic in their grandeur—have played their parts on the blood-stained fields of Ilion.

Now comes the journey home.

The Odyssey, Homer’s companion epic to The Iliad, begins not with battle, but with absence. Not with glory, but with longing. And not with a hero at the peak of his might, but with a man adrift—far from home, far from peace, far from himself. Odysseus, king of Ithaca, has not returned. Ten years after the war, he is still wandering.

Where The Iliad is the epic of wrath, of honor and loss on the battlefield, The Odyssey is the epic of return—of identity, memory, endurance, and reconciliation. It is a tale of monsters and gods, but also of fathers and sons, of lovers, of household servants, of cunning and craft. It is a poem as much about storytelling as it is about survival.

As we set out on this new journey—reading one book per week over six months—you will discover not just a sequel to The Iliad, but a reshaping of the epic genre altogether. Today, we will explore the deep ties between the two poems, introduce the characters and settings of The Odyssey, examine its historical role in ancient Greece, and unpack why it remains a profound text for our times.

From Ilium to Ithaca: The Bridge Between Two Epics

Though The Odyssey follows The Iliad in traditional reading order, it does not pick up directly where the war left off. Rather than chronicling the fall of Troy itself (a subject treated in lost epics like the Little Iliad and Sack of Ilium), Homer turns to the consequences of war—namely, the fates of those who survived it.

In this way, The Odyssey is less a continuation and more a companion—a thematic reflection in which the values of The Iliad are questioned, inverted, and sometimes reaffirmed.

Where The Iliad exalts strength and martial honor, The Odyssey privileges cunning (metis), patience, and adaptability. Odysseus is not the strongest of the Greeks—Achilles held that title—but he is the most resourceful. His heroism lies not in slaying foes head-on but in navigating the world’s unpredictability with wit and guile.

The echoes of The Iliad are everywhere in The Odyssey, but often refracted through a different lens. The gods return—Zeus, Athena, Poseidon—but their roles shift. Athena becomes a protector, a guide. Poseidon turns into a wrathful antagonist. And most poignantly, the characters remember Troy with weariness and sorrow. It is not glory they recall, but trauma. The war was long, and its scars endure.

At the center of The Odyssey stands Odysseus, a hero many of us feel we already know. We met him in The Iliad as a clever speaker and tactician, and now we meet him again—but not immediately. For the first four books of The Odyssey (commonly called the Telemachy), Homer withholds Odysseus’ presence, centering instead on his son Telemachus and his wife Penelope.

This narrative delay is crucial: The Odyssey is not merely Odysseus’ story. It is the story of a family sundered by war and distance, trying to hold onto identity in the face of uncertainty.

Let us meet the key players in this epic:

Odysseus: King of Ithaca, hero of Troy, wanderer of the seas. Known for his cunning and eloquence, he becomes a deeply human figure over the course of the epic. His challenges are not just monsters and gods, but identity, loyalty, temptation, and the restoration of his home.

Penelope: Odysseus’ wife, queen of Ithaca, famed for her faithfulness and intelligence. Besieged by suitors who believe Odysseus is dead, she fends them off through clever ruses. Her quiet resistance and longing are central emotional threads in the poem.

Telemachus: The son of Odysseus and Penelope. When the poem begins, he is a young man searching for his father—and for a sense of himself. His arc is one of maturation, a coming-of-age narrative within an epic of return.

Athena: The goddess of wisdom and war, she serves as protector of Odysseus and Telemachus. Disguising herself as Mentor, she nudges events toward resolution, embodying the theme of divine guidance and fate.

Poseidon: The god of the sea, enraged by Odysseus’ blinding of his son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. He becomes Odysseus’ primary divine adversary, extending the journey with storms and shipwrecks.

The Suitors: A band of arrogant nobles who occupy Odysseus’ home, vying for Penelope’s hand and depleting Ithaca’s resources. They represent social decay and the threat of disorder.

Eumaeus and Eurycleia: Odysseus’ loyal swineherd and nurse, respectively. Their fidelity contrasts with the treachery of others and underscores the theme of recognition and reunion.

Odysseus’ adventures are episodic and vivid. You will encounter the Lotus-Eaters, the Cyclops, Circe the enchantress, the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, and the land of the dead. But these episodes are more than mythic set-pieces—they each test aspects of Odysseus’ character and explore the boundaries of human endurance and intellect.

Historical Significance in Ancient Greece

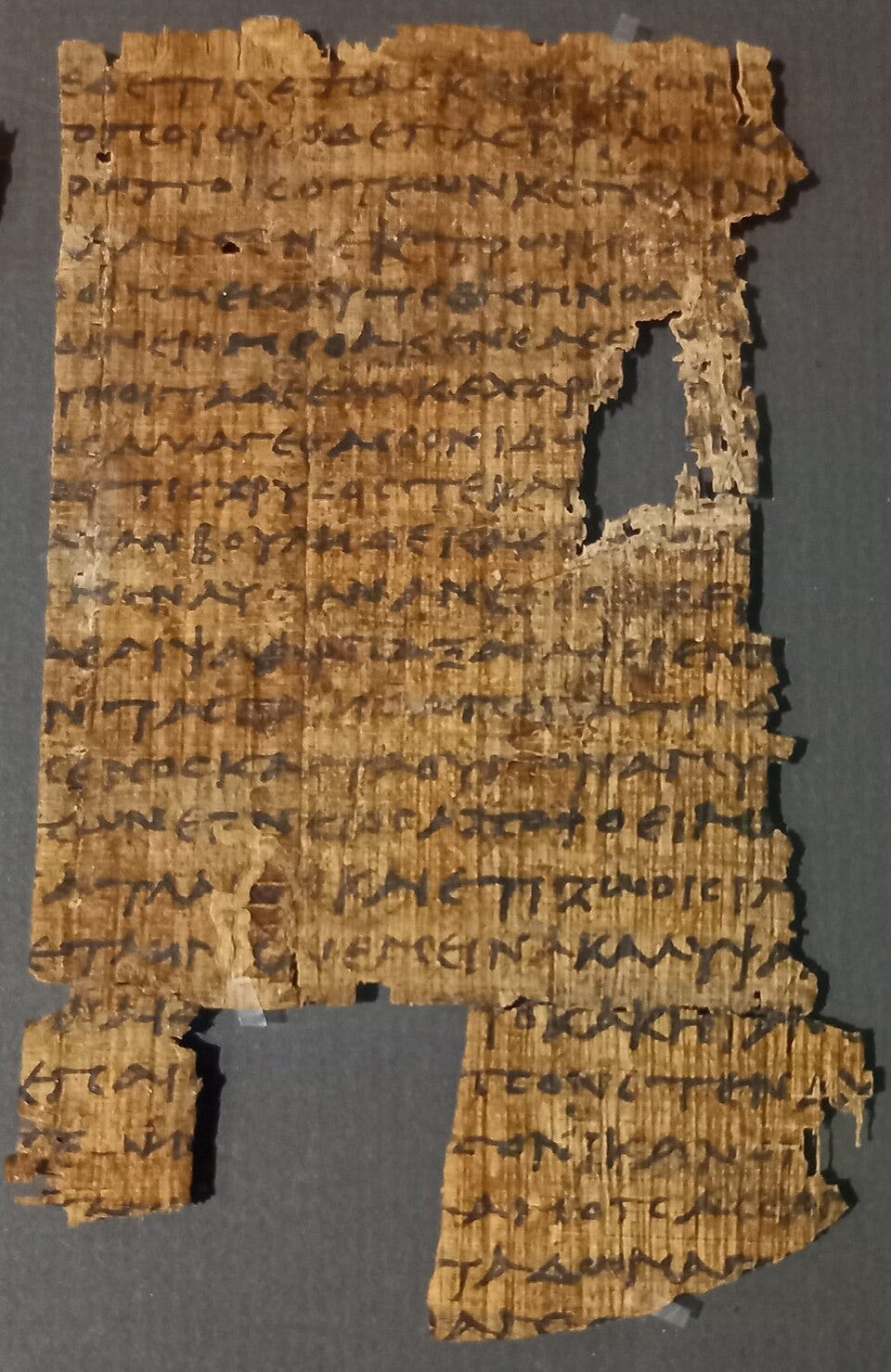

The Odyssey, like The Iliad, was likely composed around the 8th century BCE, though its material draws from oral traditions that may be centuries older. While both epics were attributed to Homer, many scholars believe they may have been composed by different poets or communities and later unified through performance.

In ancient Greece, The Odyssey served as both entertainment and education. Recited by rhapsodes at festivals and in the symposium, it was a vessel for cultural transmission—preserving values, history, and mythology. It shaped notions of hospitality (xenia), loyalty, justice, and the proper roles of kings and kin. It was not only a story but a social blueprint.

Importantly, The Odyssey offered a different model of heroism. In a society that valued strength, the poem proposed that cleverness, emotional restraint, and endurance were also marks of greatness. This shift was influential in literature, drama, and even philosophy. Socrates, for example, praised Odysseus for his self-command.

Moreover, the poem’s emphasis on home (nostos) and the pain of displacement resonated deeply with a seafaring people. Odysseus was not a distant, godlike figure—he was a man struggling to get home, like so many Greeks who traveled, traded, and fought across the Mediterranean world.

Why Read The Odyssey Now?

In our fragmented, fast-moving age, The Odyssey speaks with timeless clarity. We, too, are wanderers—navigating an overwhelming world, seeking connection, struggling with identity, resilience, and the meaning of home.

Odysseus’ journey is a metaphor that transcends its time. He encounters distraction, deception, loss, and transformation. He forgets himself (with Circe, with Calypso), and he must remember who he is to return. We recognize these rhythms in our own lives—moments when we are tested, when we must choose between comfort and courage, illusion and truth.

Penelope’s long vigil also holds contemporary weight. She waits, not passively, but with agency and intellect. Her story is a counter-narrative to the hero’s—an enduring depiction of female fidelity and emotional strength in a world of violence and uncertainty.

In an era of exile, migration, and shifting cultural identities, The Odyssey asks enduring questions:

What does it mean to come home?

Can one ever truly return?

Who are we when we are stripped of status, armor, and name?

These questions animate both the poem and our world. They are why The Odyssey is not just a tale of long ago—but a mirror for today.

Thematic Arcs to Watch For

As we journey through The Odyssey, consider these recurring themes. They will help deepen our reading and foster rich discussion:

The Search for Identity

Odysseus’ journey is not just physical—it is existential. At various points he is “nobody,” a castaway, a beggar. Who is he beneath the heroic mask? And how is identity shaped by memory, recognition, and action?The Nature of Heroism

How does Odysseus’ heroism compare to Achilles’? Is his cunning noble or suspect? What does Homer suggest about different models of greatness?Homecoming and Belonging

Nostos is central—both literal (returning to Ithaca) and metaphorical (reclaiming the self). What does it mean to arrive home changed? What are the costs and rewards of return?Hospitality and Justice

Hospitality (xenia) was sacred in ancient Greece. Observe how Odysseus is treated by hosts and how he, in turn, enacts justice against the suitors. When does vengeance become justified? When does it cross a line?Storytelling and Memory

The poem is layered with narration: Odysseus tells his own story; bards recount legends; Penelope and Telemachus cling to fragmented news. How does storytelling shape identity and truth?The Feminine Voice and Perspective

Penelope, Circe, Calypso, Nausicaa—female figures in The Odyssey are complex and powerful. How do they shape the narrative? What do they represent?Fate and Divine Intervention

As in The Iliad, the gods are ever-present. But in The Odyssey, fate often feels more personal, even intimate. Athena’s role is nurturing; Poseidon’s wrath is vendetta. What does this say about divine justice?

A Journey Worth Taking

As we prepare to read The Odyssey, think of it not only as a sequel to The Iliad, but as a vital complement—a second half of the ancient human experience. If The Iliad is about who we are in war, The Odyssey asks who we are in peace. If one is about honor and grief, the other is about home and endurance.

In its span of twenty-four books, we will cross oceans, enter palaces, descend into Hades, and sit in quiet rooms where reunion and recognition crack open the soul. We will wrestle with language, symbolism, and moral ambiguity. And we will emerge—like Odysseus—altered by the journey.

There is no better time than now to read The Odyssey. We live in a world where people are always arriving, leaving, searching. Where the definition of “home” shifts with every generation. In reading Homer’s second great epic, we are reminded that even in the face of gods and monsters, it is love, memory, and perseverance that carry us forward.

So gather your wine-dark seas of discussion, raise your metaphorical sails, and prepare to chart the long and winding course of Odysseus. For as Homer knew—and as you will discover—every reader who opens The Odyssey becomes a voyager, and every voyage a return.

“Where The Iliad is tragic, The Odyssey is romantic: not in the sentimental sense, but in its insistence that love, loyalty, and homecoming matter more than martial prowess.” —Bernard Knox, Introduction to The Odyssey

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 1. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled Athena Inspires the Prince and covers pages 77-92. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled The Boy and the Goddess and covers pages 105-119.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

I could not hang with The Iliad (wimp ). But I’m here to start the journey again with Odyssey.

I'm in and thank you, Matthew, for leading this read.

FYI, I found a free pdf version here (my copy was not a Fagles translation) - file:///C:/Users/finds/Documents/Odyssey%20Robert%20Fagles%20Translation%20Numbered.pdf