Exploring Life and Literature.

“So the corpse lay there, stretched in the dust, the horses trampling him flat as chariots churned around him— a storm of dust rose up from the bloody press.”

Dear friends,

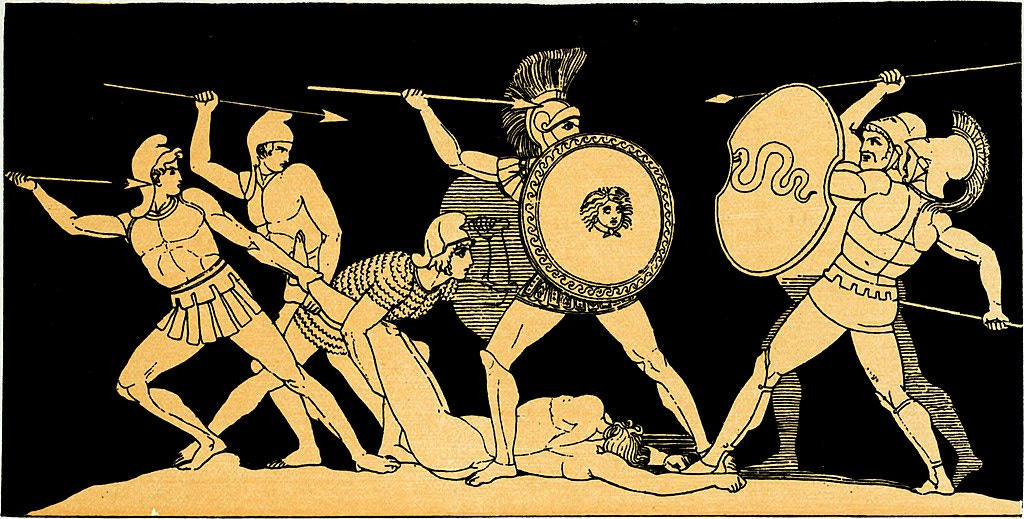

Book 17 of The Iliad is a whirlwind of violence, honor, grief, and persistence. The scene opens in the thick of the Trojan War, in the immediate aftermath of Patroclus’ death at the hands of Hector. The loss of Achilles’ closest companion sets off a savage and emotionally charged sequence of events as the Greeks and Trojans clash over Patroclus’ body. What follows is not just a battle for a fallen comrade, but a contest of values, identities, and allegiances.

Menelaus, the king of Sparta and husband to Helen—the woman whose abduction sparked the war—plays a central role in this book. Seeing Patroclus slain, he positions himself protectively over the body. The scene is deeply evocative, drawing on the ancient code of honor that permeates Homeric warfare: to allow an enemy to strip and desecrate the body of a fallen hero is an unforgivable disgrace. As Menelaus fends off Euphorbus, a Trojan warrior who first wounded Patroclus before Hector delivered the fatal blow, we witness the tenacity that defines the Greek ethos. Menelaus kills Euphorbus but cannot maintain control of Patroclus’ body on his own.

Hector reappears, eager to take possession of the corpse to further demoralize the Greeks. Despite his prowess, Hector’s motivations reflect a growing ambition that borders on recklessness—a hunger for glory that blinds him to the deeper moral and spiritual consequences of war. Apollo, still supporting the Trojans, bolsters Hector’s courage, warning him against hesitation. The divine interference continues as Athena and Apollo manipulate the battlefield, framing the fighting as a struggle not only between men but also between gods with conflicting agendas.

Enter Ajax, towering and resolute, who joins Menelaus to defend Patroclus’ remains. With Ajax’s support, the Greeks stabilize their position momentarily. Ajax stands as a pillar of raw strength and integrity, often portrayed as the silent hero of the Achaean army. The epic depicts a tug-of-war not only for the physical body of Patroclus but also for symbolic dominance—each side understands the corpse represents more than flesh; it represents courage, memory, loyalty, and identity.

The Greeks strive to rescue the body to honor Patroclus and appease Achilles, who has yet to reenter the battle. Without Achilles, the Achaeans remain strategically weakened. However, the narrative in Book 17 swells with a collective resilience that is powerful in its own right. Nestor’s son, Antilochus, is sent to inform Achilles of his friend’s death—a moment that anticipates the explosive emotional upheaval soon to come.

The battle intensifies, taking on the character of chaos. Weapons clash, shields splinter, and warriors fall. Fagles’ translation masterfully maintains the rhythm and energy of the original Greek, capturing the momentum and carnage of this prolonged engagement. As the tide of battle shifts back and forth, each side suffers significant losses, and even the gods seem wearied by the unrelenting bloodshed.

As dusk nears, the Greeks begin to gain an advantage, bolstered by Ajax and Menelaus’ dogged determination. Hector, at times exultant and at others nearly overmatched, exhibits a complex spectrum of courage and desperation. The Trojans are eventually pushed back, and the Greeks manage to carry Patroclus’ body away. Yet victory feels hollow, tinged with the pain of loss and the foreshadowing of Achilles’ looming return.

Book 17 is a study in transitions and tensions: between life and death, pride and humility, human will and divine manipulation, individual valor and collective duty. While the narrative is anchored in the brutal mechanics of ancient warfare, its emotional and philosophical core transcends its setting. What makes this chapter especially poignant—and relevant to us today—is how deeply it examines the human condition in moments of crisis.

First, we must consider the portrayal of honor and grief. In Homeric culture, to die in battle is not inherently tragic—it is expected, even noble. The real tragedy lies in the manner of death and the treatment of the body. This is where Menelaus and Ajax shine. Their decision to protect and recover Patroclus' body stems not merely from tactical necessity but from a deep cultural and emotional understanding of what it means to honor the dead.

Modern parallels abound in how we memorialize and remember our fallen. Consider the ways in which nations today conduct military funerals, maintain war memorials, and repatriate the bodies of soldiers. These acts are rituals of dignity that mirror the Greeks’ actions in Book 17. The physical remains of Patroclus become a site of meaning—much like a flag-draped coffin or an eternal flame at a tomb. The intense need to preserve dignity in death is one of the enduring human instincts illustrated by Homer.

The role of comradeship is also central. Menelaus and Ajax do not defend Patroclus out of duty alone—they do so out of love and respect. This bond among warriors, known in Greek as philia, is forged not through ideology or politics, but through shared suffering and mutual reliance. In modern contexts, especially in military service or crisis situations, we still see this dynamic at play. Veterans often speak of fighting not for a cause, but for each other. The power of these human connections is timeless, and Homer captures their emotional gravity with astonishing clarity.

Another critical theme in Book 17 is the complex figure of Hector. As a literary character, Hector is one of the most compelling in The Iliad. Here, he is torn between glory and responsibility. Encouraged by Apollo, he presses on aggressively. Yet he is constantly aware of the risks, of the thin line between valor and ruin. This duality—courage tinged with dread—is a deeply modern idea. Today’s leaders, whether in politics, activism, or corporate life, often grapple with this tension. How far should one go in the pursuit of greatness? At what cost? Hector’s arc in Book 17 serves as a cautionary tale against overreaching, as well as a portrait of ambition in its most conflicted form.

The gods’ continued interference also speaks to contemporary concerns. Apollo, Athena, and others act not with human interests in mind, but for their own inscrutable goals. This motif invites us to consider the forces in our own lives—systems, ideologies, histories—that seem to guide our actions but remain beyond our control. Whether we frame these forces as fate, systemic power, or the randomness of chance, The Iliad remains deeply aware of human vulnerability in the face of the unknown.

Book 17 also reflects on the relationship between grief and transformation. Though Achilles does not yet return to the battlefield in this book, the ripples of Patroclus’ death begin to change him. The coming books will see Achilles transformed from rageful exile to avenger and mourner. His grief is foreshadowed here in the desperate attempts to recover Patroclus’ body. This speaks to the way loss reshapes identity—an experience that resonates in modern life across all cultures and classes. Loss is not just an absence; it’s a catalyst for change.

In a world still plagued by war, political divisions, and personal crises, The Iliad, and particularly Book 17, retains its urgency. It teaches us that courage often exists not in victory but in struggle; that dignity survives even in defeat; and that grief, though unbearable, is a mark of love and a herald of transformation. These truths echo down the ages and into our own fractured world.

Book 17 is a narrative crucible, melting together personal loyalty, honor, ambition, and grief. Through the heroic efforts of Menelaus, Ajax, and others, we see that the human spirit—tested though it is—can still stand against the tide of chaos. And in Hector’s wavering courage, we see our own struggles with pride and purpose. The timeless power of Homer’s storytelling lies in this balance between myth and meaning, between ancient battlefield and the quiet wars we fight every day.

“Menelaus, dear to Ares, flared in anger now to see Patroclus there, sprawled by the bronze spear.”

The Historical and Mythological Menelaus

Menelaus stands as one of the more enigmatic figures of the ancient world—a king often overshadowed by louder heroes like Achilles, wiser kings like Odysseus, or more tragic figures like Hector. Yet his role in Greek mythology and literature is indispensable. As the king of Sparta, the husband of Helen, and a major player in the Trojan War saga, Menelaus straddles the boundary between myth and potential historical figure, offering a complex lens through which we can examine kingship, honor, and emotional restraint.

From a historical standpoint, the existence of Menelaus cannot be verified in the archaeological record. However, the city he ruled—Sparta—was very real and prominent in both the Mycenaean and Classical periods of Greek history. The epics in which he appears, particularly Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, reflect a much earlier, heroic age, typically dated around the 12th or 13th century BCE, during the late Bronze Age. This was a time of palace economies, regional kings, and constant warfare among rival states and city-kingdoms. While no direct evidence of Menelaus has been found, the figure likely represents a composite or an idealized version of Bronze Age royalty—one grounded in the culture of honor, martial obligation, and dynastic politics.

Menelaus is a member of the Atreid family, one of the most cursed and tragic lineages in all of Greek myth. His brother, Agamemnon, commands the Achaean army, and his wife, Helen, is both prize and person—her abduction by Paris of Troy provides the inciting incident for the Trojan War. Yet Menelaus is not portrayed as vengeful or blustering. Rather, his persona is one of restraint, dignity, and endurance. These traits are consistently shown in contrast to the more explosive personalities that surround him.

Menelaus in Literature: Homer and Beyond

In Homer’s Iliad, Menelaus emerges not as a centerpiece but as a necessary axis around which much of the story turns. His loss—of Helen, of personal honor—initiates the war, but his actions in the text are rarely driven by blind rage. When he does enter the fray, as in Book 3 where he duels Paris, he fights with purpose and discipline. His interactions with Helen, especially in later epics like the Odyssey, reveal layers of tenderness and complexity.

In The Iliad, Menelaus does not display the unrestrained fury of Achilles or the cunning of Odysseus. Instead, his strength is in loyalty and persistence. In Book 17, for instance, he is among the first to protect the body of Patroclus after the young warrior’s death. This act of courage and honor affirms his place not only as a capable warrior but also as a man devoted to preserving the dignity of his comrades. He acts out of respect, not impulse.

Homer seems to deliberately present Menelaus as a foil to the more volatile characters in the epic. Where Achilles isolates himself, Menelaus works with others. Where Agamemnon is arrogant and overbearing, Menelaus is measured. And where Paris is cowardly and self-indulgent, Menelaus is gallant and restrained. This careful characterization extends into the Odyssey, where he hosts Telemachus, son of Odysseus, and offers counsel and gifts. His home in Sparta is depicted as peaceful and prosperous—a symbolic restoration of order after the chaos of Troy.

Beyond Homer, Menelaus appears in other classical works, including Euripides' Helen, where the playwright toys with alternate versions of the myth. In this tragicomedy, Helen never went to Troy at all; instead, a phantom version of her was taken by Paris, and the real Helen remained in Egypt. Menelaus, shipwrecked and weary after the war, finally finds her and reclaims his life. This version emphasizes the emotional toll the war took on him and underscores his perseverance.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, a Roman epic drawing heavily from Homeric tradition, Menelaus is a peripheral figure but nonetheless part of the larger mythological ecosystem. He represents continuity, tradition, and the enduring consequences of honor-based warfare.

Kingship and Leadership: The Spartan Model

To understand Menelaus as a leader, one must understand what kingship meant in Bronze Age and Archaic Greece. Kings were not absolute rulers, but basileis—first among equals. Their authority rested on land ownership, prowess in battle, lineage, and the ability to command loyalty from warrior elites.

Menelaus, as king of Sparta, inherits a kingdom not yet the militaristic juggernaut it would become in Classical times. In Homeric epics, Sparta is wealthy and fertile, a place of beautiful palaces and cultivated leisure. Menelaus rules not through terror or conquest, but through a sense of measured obligation and hospitality. His leadership is consultative, not authoritarian.

Unlike Agamemnon, who frequently asserts dominance and suffers the wrath of his peers for it, Menelaus appears more adaptable and pragmatic. He is diplomatic when necessary, fierce when required, and, above all, dutiful. His pursuit of Helen is not framed as a personal vendetta but a national cause, fulfilling his oath to uphold the honor of the Achaean coalition.

In The Iliad, we see glimpses of his leadership under pressure. In battle, he is not the most fearsome, but he is one of the most consistent. His effort to retrieve Patroclus’ body in Book 17, for example, is not merely an act of bravery—it is an act of loyalty and moral leadership. He risks himself not for glory, but for what is right. Such leadership is quiet, but it resonates deeply.

Relatability and Modern Relevance

What makes Menelaus a figure of lasting relevance is not just his role in the war, but the very human traits he exhibits throughout the epics. In a world obsessed with extremes—rage, revenge, conquest—Menelaus embodies the middle path. He is not flawless, but he is consistent. He is not the strongest, but he is dependable. These are qualities that modern readers can relate to, especially in an age where leadership is so often measured by spectacle rather than substance.

In his marriage to Helen, we also see the messy complexity of love, loss, and reconciliation. Unlike Achilles, whose grief isolates him, or Odysseus, who longs for his homeland with a mythic singularity, Menelaus seems to live in the gray zones of human emotion. He forgives Helen—not blindly, but reflectively. He allows himself to be shaped by events, not destroyed by them. His path is not heroic in the traditional sense, but it is deeply human.

In contemporary terms, Menelaus might be seen as the everyman leader—the person who, though not always in the spotlight, holds things together. In workplaces, communities, and families, we often rely on people like Menelaus: dependable, humble, principled individuals who may not shout the loudest but act with integrity.

He also reflects the enduring burden of honor. In our time, honor may no longer demand war, but the ethical challenges remain. Menelaus reminds us that leadership often requires restraint, that courage is sometimes quiet, and that dignity in the face of adversity is as heroic as any battlefield victory.

The Enduring Echo of a Noble King

Menelaus may never have stood at the center of Homer’s grand epics, but his legacy is indelible. In the long shadow cast by Achilles’ wrath and Odysseus’ cunning, Menelaus offers a third model—of duty, persistence, and moral leadership. Whether he was ever a real king or a symbol crafted from collective memory, his narrative speaks to us with surprising clarity across the centuries.

His story tells us that not all heroes are forged in the furnace of rage. Some are tempered by loyalty, tested by loss, and proven in quiet acts of courage. As a husband, king, warrior, and host, Menelaus shows us that greatness does not always roar. Sometimes, it endures.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

Consider what the fierce battle for Patroclus’ corpse says about honor, legacy, and the role of the body in ancient Greek cultural and religious beliefs. Why is recovering the body so important, and how does this reflect their understanding of death and the afterlife?

Discuss how Menelaus reacts to Patroclus’ death and whether his actions—both in combat and in preserving honor—enhance or complicate his role as a central character. How does he compare to other leaders like Hector, Ajax, or Agamemnon?

Apollo and Athena both play active roles in this chapter. What does their manipulation of battle suggest about the limits of free will? How might this reflect ancient Greek views on fate, divine favor, and responsibility?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 18. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Shield of Achilles and covers pages 467-487. In the Wilson translation, it is called Divine Armor and covers pages 439-461.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I particularly like how your essay draws a line from the determination of the Achaeans to protect Patroclus's corpse to our modern rituals to honor those who have made the ultimate sacrifice for their country. It seems that this is something universal throughout all cultures and from ancient times to the present. Your essay caused me to ponder the rationale for this practice. To say that it is a way to honor the fallen and express communal appreciation and gratitude for their sacrifice seems inadequate to explain how deeply ingrained this tradition is in our psyche. I lack the words to explain adequately why memorializing and honoring soldiers who are killed just feels deeply like the right thing to do - and how grievously wrong it would be not to do so.

When I read about the determination of the Achaeans to protect Patroclus' body and deliver it to Achilles, I had the nagging feeling that, in addition to motivations of honor and ritual, the Achaeans are hoping that the site of Patroclus body will spur Achilles into action. Am I just letting cynicism creep into my reading?

Your description of Menelaus, his character and motivations is eloquent. Menelaus has the qualities I would like to see in all our leaders, both military and political.

Hector wearing Achilles armor… I get that taking opponents armor as treasure, but wearing it tauntingly? It seems like a particularly bad idea, like poking a bear with a hornet’s nest. I’m trying to think what a modern equivalent would be?