Pilgrims in the Machine - An Interview with Peco Gaskovski

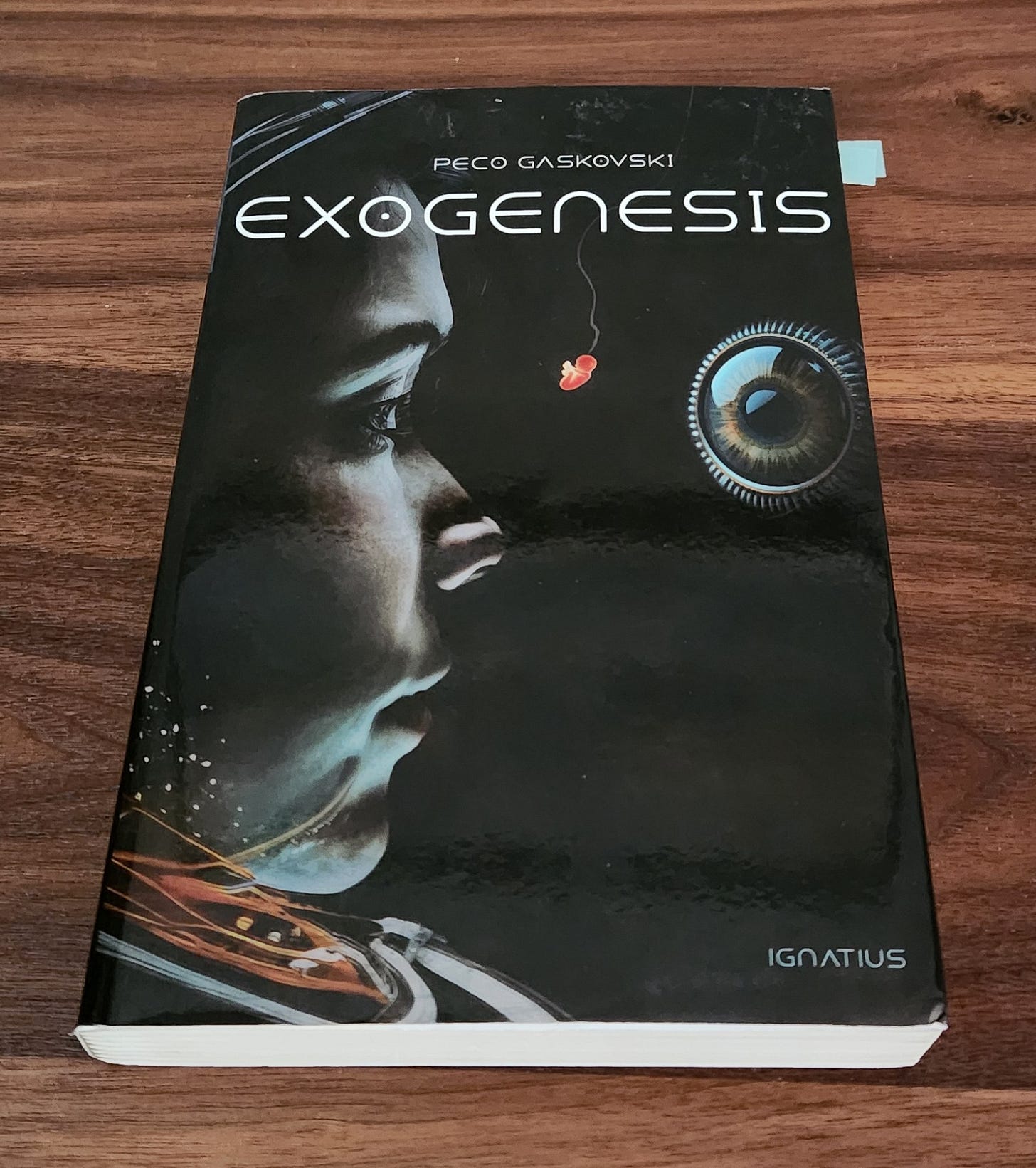

And a review of his book - Exogenesis

Exploring Life through the Written Word

Dear friends,

I first encountered

Gaskovski and his wife, , through their excellent publications, Pilgrims in the Machine and School of the Unconformed. Their erudite writing and research on topics pertinent to our times intrigued me. I love writing that forces me to think and challenges me to understand my beliefs better. Peco and Ruth have helped me to flesh out aspects of my personal philosophy on life in the machine age. When Peco’s book, Exogenesis, was recommended to me as a choice for my 2025 reading plan, I jumped on it. I have read it front to back three times. Not only because it is a great story, which it is. More so, I keep coming back to it because of how relevant and seemingly prescient the message is. Today, technology allows us to create almost anything we want. But should we? And in the act of creation, what becomes of us and our humanity?In Exogenesis, Peco Gaskovski delivers a stunning, cerebral exploration of humanity’s confrontation with its own fragility and potential transcendence. As both a story and a philosophical meditation, the novel succeeds brilliantly. Peco’s prose is elegant without pretension, balancing vivid storytelling with existential inquiry. His greatest strength lies in his ability to weave complex scientific and metaphysical ideas into a narrative that remains emotionally resonant and deeply human.

The book’s thematic ambition is impressive: it wrestles with questions of consciousness, faith, technological evolution, and the tension between destruction and renewal. Peco avoids the common sci-fi pitfall of reducing characters to mere ideas; his protagonists are fully realized, vulnerable, and compelling, which makes the novel’s intellectual stakes feel urgent rather than abstract.

"Exogenesis wrestles with consciousness, faith, and technological evolution, without losing sight of the human heart."

A minor challenge, if it can be called that, lies in the novel’s density—at times, readers less familiar with philosophical or theological discourse may find themselves working harder to keep pace with the author’s intricate reflections. Yet even these moments reward patient reading, inviting reconsideration and deeper immersion.

The implications of Exogenesis are far-reaching. Peco suggests that humanity stands at a precipice: our scientific advancements may either estrange us from our origins or offer a path toward a deeper, more sacred understanding of life. The novel quietly warns that unchecked technological ambition risks a future of profound alienation if divorced from humility and ethical reflection. Yet it also holds out hope—perhaps even a quiet faith—that new creation can lead to unexpected forms of redemption.

In a world increasingly dominated by rapid technological change, Exogenesis is both a mirror and a guide. It challenges us not simply to ask what we can create, but why we should create—and who we wish to become in the process.

• Peco, thanks for your willingness to chat with me and my readers. Tell us a little about yourself. Where are you from originally, and where do you live now? What does your family and home life look like? How do you like to spend your time?

My parents were Macedonian immigrants from the former Yugoslavia. They came to Canada in the 1960s, and I was born shortly after their arrival. I still live in Canada, in what I call “the borderlands” between the urban sprawl and Old Order Mennonite country. This is a region where you’re almost as likely to see a horse-drawn buggy as an electric car. I also recently became a Swiss citizen, as my wife Ruth is Swiss. We’ve spent a lot of time in Switzerland over the past 20 years, to the point that it’s become like a second home to me. Ironically, the Old Order Mennonites who live near us are descended from Swiss Anabaptists in the 1500s. Their native language is still a peculiar dialect of Swiss-German that my wife and our kids, and even I, can vaguely understand.

I would describe my life as a kind of meditative novel. By which I mean, my interior world is full of ideas and imagination and aesthetic dimensions, while my exterior world is pretty quiet, consistent, and routine. So on the one hand I do a lot of thinking and writing—something which has been part of my daily life ever since I was a child—while on the other hand I have my job as a psychologist, and my role as a father and husband. Our home, though orderly, is also a busy place where we homeschool our kids (now all teens, with one in university), enjoy a library of over 3000 books, host feasts with friends, and keep a coop of chickens whose greatest thrill, other than food, is flying over the fence.

• Your novel, Exogenesis, explores deep philosophical and existential questions. What inspired you to write this particular story, and how did your experiences shape its themes?

I began thinking about the story in the early 2020s. At that time, people like Paul Kingsnorth were writing about how technology was penetrating more deeply into our daily lives, while the Covid pandemic and frequent lockdowns meant that many of us were spending more time living through digital interfaces. So I found myself wondering, Where is technology going? What will the future look like?

The other theme that has long concerned me is political disintegration. The US in particular, but also other parts of the West, are rapidly dividing into a more progressive society and a more traditional or conservative society. So I’ve often wondered, How far will this division go, and how might technology become entangled with it?

All these questions were the creative fuel that got the story bubbling in my mind. Exogenesis is set a couple hundred years in the future, and imagines an America split into two distinct societies. One is a low-tech society of traditional people who live by farming, have big families, and practice religion, whereas the other is a high-tech society centered in a secular megacity. I created the main character, Maelin, to be caught in the middle, so that I could explore the tensions between these two worlds.

• The novel delves into the intersection of science, consciousness, and identity. How do you see these ideas reflecting broader societal questions about what it means to be human?

Car-makers often manufacture the underbody for their vehicles by welding together numerous separate parts. Then came the giga press, a giant die-casting machine where molten aluminum is poured into a mold and turned into a single piece. That’s good for car-makers, but what happens when the same principle is applied to human identity? Can we giga-press ourselves into whatever we want to be? How much of ourselves can we actually invent and re-invent? Is there anything “essential” in human identity? These questions have always fascinated me.

Currently, most of our giga-pressing is carried out through belief, ideology, and behavior. But one day, conceivably, we might have technologies that do some of the die-casting for us. In Exogenesis, the most obvious example is in the way children are born among the people living in the high-tech megacity. Human embryos are grown in artificial wombs outside the woman’s body. Parents actually create hundreds of embryos, but are only allowed to choose one to grow to full term. This “chosen” one is determined by analyzing the genetic profiles of each embryo, and picking the one that seems best based on intelligence, personality, beauty, health, and other characteristics. Basically, people giga-press their idealized baby into existence based on optimal genetic profiling—while discarding (aborting) all the other embryos.

And this is not a dystopia for these people. They see it as good and liberating. It frees them of the need for natural pregnancy, which they view with moral disgust, while maximizing their freedom to invent the kind of child and “family” they want. At the same time, there are no actual families, as children are raised in care homes by state professionals, and there are no more mothers and fathers, only “guardians”.

All this might seem like science fiction or dystopia, but elements of it have already arrived in our own world.

Earlier this year, the Guardian published a story about a US startup company that is charging wealthy couples “to screen embryos” for IQ. This was apparently discovered through undercover footage. According to the Guardian piece,

The recordings show the company marketing its services at up to $50,000 (£38,000) for clients seeking to test 100 embryos, and claiming to have helped some parents select future children based on genetic predictions of intelligence. Managers boasted their methods could produce a gain of more than six IQ points.

Other genetic factors, such as health, could also be screened, in essence allowing parents to select the children most likely to be “disease-free, smart, healthy”.

My novel—which fictionally describes the same technique—was published in 2023, and already the reality is catching up to the fiction.

Meanwhile, in 2023, the FDA (the Food and Drug Administration in the US) commenced discussions on how to move research on artificial wombs from animal studies to human trials. So, our society is on the verge of a new technology that, one day soon, will allow (highly) premature babies to grow to full term outside of a woman’s body.

Combining the above two technologies could eventually lead us to an Exogenesis-type society. That still might be a long way away, but then again, innovations sometimes happen faster than we can keep up, and the convergence of corporate ambition and people’s desire for maximum convenience could override the profound ethical and moral concerns.

Is there anything essential about womanhood, family, or natural pregnancy? Do these things play any indispensable role in “what it means to be human”? If yes, or no, then who decides, and on the basis of what values?

• Your prose is both lyrical and intellectually rigorous. How do you balance storytelling with exploring complex scientific and philosophical ideas?

My natural mental alchemy has always been a blend of story and fantasy on the one hand, and concept and analysis on the other. This is actually a potentially dangerous mix for a writer, as stories should “show” not “tell”. Abstraction tends to interfere with storytelling. So it begs the question, is it possible to write fiction that explores ideas in a way that, rather than weakening the story, makes it more vivid or gripping in the mind of the reader? I don’t know if Exogenesis succeeds in this, but that was part of the creative impulse.

• Some writers say their stories evolve as they write. Did Exogenesis unfold as you initially envisioned it, or did the story take unexpected turns?

It didn’t unfold the way I expected at all. I started and then abandoned the story twice within one month. Something about the early conception was off. Then I went back to it a third time, and was finally able to imagine the story in a way that seemed to work.

Even then, it didn’t go the way I planned. I used to plot out all my chapters before writing, but now I tend to begin with a broad sense of a beginning, middle and ending, which tends to shift and change over the course of the writing. I place a lot of emphasis on imagining the settings, and more than anything to see things through the eyes of the characters. If I have any advice for writers—and this is advice I keep giving to myself—get to know your characters well, especially their desires, flaws, and unique qualities. If the characters are strong and distinct, they’ll often do the plot writing for you, and constantly surprise you. The best writing always happens when the writer is surprised. If the writer is, you can be fairly sure the reader will be too.

• What role do you believe speculative fiction plays in helping us grapple with real-world ethical and existential dilemmas?

In speculative fiction—by which I mean science fiction, fantasy, and similar genres—there is a lot of world-building. For speculative writers, this can be one of the most exciting parts of the writing process, because it allows you to create any sort of universe you want. This also gives the writer a level of freedom for exploring ethical, moral and existential questions in ways that just aren’t possible in any other genre.

Earlier I mentioned new birthing technologies that may lead us to a more Exogenesis-type society, but the novel also explores other Exogenesis-like realities that are slowly developing in our own world, like mass surveillance through cameras, sensors and drones, or the use of psychedelics to “create” spiritual experiences. As I wrote the novel, I often found myself asking, Would I be comfortable living in this sort of world?

The dilemma we face with a lot of emerging technologies is that they can make life more stimulating, safe, or convenient, yet at the cost of our ethical values or integrity. I hope the novel gets people thinking about these issues more intentionally.

• Does the book suggest a reconciliation between scientific exploration and religious belief, or do you see them as fundamentally at odds?

In terms of my own thought process, I believe that scientific and religious belief have something significant in common: they both dig into the deepest fabrics of reality and ask, What’s there? Within the novel, however, there is no reconciliation between science and religion. If anything, the novel explores how science and religion can divide people along ideological lines, giving rise to radically different values and ways of living.

We face the same divide today. Is everything in the universe merely material, just physical stuff in different configurations, or is there a spiritual dimension as well—a God, a conscious and creative Mind that works through the material? These aren’t just abstract questions for philosophers. Our answers to these questions determine our basic values, our everyday choices. If Western society or large portions of it start to disintegrate, it will be, I suspect, not simply due to economic factors or some other external stress like war, but because the materialist-religious divide will fracture our feelings of trust in each other.

• Some argue that AI will ultimately lead to a post-human future, while others believe it will deepen our appreciation of what makes us human. Where does your novel stand in that debate?

At one point in the story, the character Arek is critical of the “Ministry of Behavioral Algorithms”, a government department where data from countless cameras in the megacity are transmitted to a warehouse of machines stacked a hundred floors deep. Here, the data are analyzed and used to evaluate citizen behavior, in order to reward compliant citizens and to punish noncompliance and criminality. As Arek observes, the digital “Eyes” that watch everybody “become our true judges. Our moral conscience. The ones we seek to please. Our God.”

The odd thing is, citizens are quite aware that they’re being watched by machines, yet they don’t experience it as an oppressive “Big Brother” like in Orwell’s 1984. They aren’t particularly troubled, just as many people today aren’t troubled that their online activities are tracked by Big Tech algorithms.

I think this is where AI might lead us. I mean a world in which machines increasingly monitor our behavior and speech, either to manipulate us for ideological reasons, or to simply find new ways to monetize our behavior. Unfortunately, I expect that many people will be okay with it, especially if they feel AI is making their lives more convenient and safe. It certainly might, but at the cost of diminishing our freedom of choice and moral responsibility. What if our moral beliefs conflict with what AI decides is “moral” behavior? What if we don’t want AI auto-filling our everyday choices?

I don’t mean to suggest that there won’t be any benefits from AI. But as a society, I feel as if we haven’t matured enough to prioritize what makes us human—cognitively, socially, physically, and spiritually—and to keep AI out of that sphere.

In that sense, Exogenesis is “warning fiction”.

• In your view, how does fiction help us better understand reality? Do you think literature has a unique role in shaping our perception of existence?

I don’t know exactly how human society began, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it involved a group of people sitting around food or a fire, and one of them telling a story about something that happened that day. This primordial experience still takes place at our own kitchen table almost every evening. I regard written literature, including novels and plays, as a further development of that original act of storytelling.

Reading literature helps us to see through the eyes of others, and in that sense it’s an empathy tool. Studies suggest that this isn’t just because people who are already empathic or have certain personality traits choose to read fiction. Rather, reading fiction itself, especially literary fiction or stories that emphasize character, can help us understand others better.

Studies also suggest that the most effective narratives, the ones most likely to go viral, activate similar brain regions across individuals, specifically areas involving attention, suspense and other intense emotion. Powerful stories can literally synchronize human minds. This is probably why groups of people who read the same literature feel a resonance not only with the books but with each other.

And unlike film, which is a more passive experience, or digital activities, which often require little cognitive effort, books work the mind, exercising it at multiple levels of perception—everything from the processing of syllables and sounds, up to activating our imagination.

I don’t think literature will ever go away, because we need stories to know who we are. Someone once suggested that our species, homo sapiens, should have been called homo narrans. I’m inclined to agree.

• Where can people connect with you online?

I periodically write on my Substack Pilgrims in the Machine, and also on my wife’s Substack School of the Unconformed. Otherwise, I’m socially offline.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Matthew, what a fine interview with such a fascinating individual. His is a voice (and elegant intellect) sorely needed to moderate discussions of how and why we pursue technology and what needs to be considered as we seek to make advances, especially given Meta's recent decision to manufacture, if that is the correct word, an AI more powerful than the human brain.

I also note that his children are being home-schooled. What rich talks and learning must go on around the table!

Always love how you weave personal insight with literary gems. Another good one.