Exploring Life and Literature

Dear Friends,

A few months ago I put out a call for submissions of short stories to share with you this month while we explore this fascinating style of literature. The response was overwhelming with more than 40 people submitting their work for my consideration. While I would love to have the space to feature them all, I selected three which really stood out to me and which I wanted to share with all of you. This is the third and final of those stories. These articles are quite a bit longer than my normal emails and may require you to open the story in your browser as it may be cut off by your email provider.

Arthur’s development as a writer was heavily influenced by cultural and family elements. A fan of shows such as The Twilight Zone, Stargate SG-1, and Star Wars, he wanted to create his own worlds and stories to fit in them. His father and grandfather were both huge influences through their shared interests and the examples they set for him. His goal is to write meaningful stories in the genres he loves; stories that process our emotions in positive ways.

I asked Arthur if he had any books he would like to recommend. He said he had recently read and been influenced by Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman. Additionally, he recommends the short story collection, Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang.

Enjoy this short story from Arthur.

October 7, 2091 - New York City

1. Integration

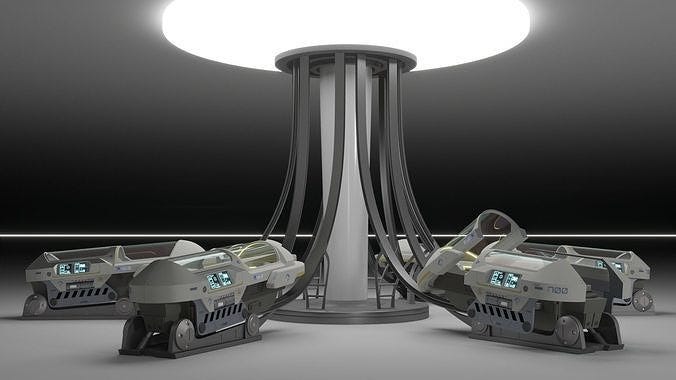

Fifteen years have passed since I last saw my son. He was one of the first "pod children," a child raised not by parents, but by simulation. The Pediatric Ontogeny Development System, or “PODs.” The abbreviation eerily fitting for the glowing silver cylinders filled with yellow liquid, where children remain unconscious and suspended for the duration of the simulation.

The process of getting kids into a pod was called podding. Children were put to sleep first, told they were taking a quick nap before seeing the doctor. After that, they were connected to signal cables, air and nutrient hoses before being placed in the pod. Then the yellow simulation liquid pours in from supply values in the sides of the cylinder and the child disappears.

I remember our son laying down, his consciousness fading. He wore his favorite shirt: an orange long sleeve with huge monster trucks beneath text that read SUPER TRUCKS. I'll never forget watching his tiny 3-year old body disappearing into the yellow goo.

I’ve missed that shirt. I’ve missed him.

He was guaranteed food and nutrients to survive and the stimulation to thrive, suspended in the pod until he was eighteen when he would emerge as a perfect kid. Prepared for adulthood. Ready to take on the world.

Some parents watch the procedure. Some can’t. I did. My wife didn’t. Couldn’t. She looked away, standing beside me, holding my hand as we wondered if we made the right decision.

We almost lost our son during podding. Just after they placed him in a pod, a pipe burst somewhere behind us. The piercing hiss from the pressure release was too much, making my ears ring like church bells. Then the power went out. My wife and I woke up on the floor, a bit sore but otherwise fine. Our son was okay. Emergency power had come back just in time.

2. Simulation

The day after podding, we woke to a quiet apartment. No laughter from our son. No mouth-made motor noises or train horns. Just us, trying to eat breakfast, knowing biologically we had to, but lacking desire.

The main wall monitor in our living room became the portal to our son. It showed his heartbeat, breaths per minute, height, weight - and all the necessary readings to know he was alive and well. Comparisons to kids his age also displayed occasionally, tracking his progress against other pod kids and the average kids out in the world. Our watches and HUDs showed the same. I could see his readings anywhere, though I haven’t been to many places, not wanting to put much distance between us.

We also had daily decision logs. Each night, we reviewed a list of potential challenges our son would encounter in the simulation. We knew if the next day would be what they called a “good sequence day,” or “bad sequence day.” An algorithm decided what a child went through. Days he might cry. Get his feelings hurt or bullied at school. Break his arm riding his bike. PODs also gave him diseases to strengthen his immune system. Medicine to cure it. Vaccinations and antibiotics. These randomized disease and injury protocols were required to simulate real life.

We even knew the times things would happen. The decision log would note that at his school lunch, no one would sit with him. At 12:13pm, he would be alone. We had to decide what our simulated selves inside PODs would do to comfort him when he came home from school.

Those discussions between my wife and I were often harder than enduring the actual sequence days. But we grew closer because of it. The mutual aching for our son forced us to come together.

Some kids got more chronic conditions like cancer or a fatal injury. We never had a sequence day like that. We’ve been lucky. Flu, ear infections, runny noses. A broken collar bone playing hockey when he was twelve. That was the worst of it.

Not all kids make it. Not all parents do either. The crazy things some parents did who didn’t have it in them. A father in Seattle tried breaking his daughter out of PODs when his decision log revealed forthcoming leukemia. A mother in Houston hired a hacker to simulate a better life in PODs than the truth at home. A father from Tampa asked for PODs to kill his simulated self because he didn’t want to be a parent anymore. It became a federal offense to mess with PODs; to manipulate synthesized child development.

I like to think I had the emotional rigor to handle it. Looking back, I’m not so proud of that. As a father, my emotions were relentless. A torrential downpour that didn't end, becoming a river flooding the landscapes of my inner being. I tried piling metaphorical sand bags up to keep the torrent at bay, but it just overflowed.

PODs was expensive, but still cheaper than keeping our son home and sending him to real school. Teaching him how to be a good person - something I felt was beyond my ability. I could barely take care of myself.

Studies conducted between 2030 and 2070 reported a steady decline in parenting capability, paired with an increase in the economic hardship of raising children. School became unaffordable except for the top 10% of earners. Primary and secondary education channels were no longer capable of keeping children engaged.

They created PODs to solve these problems, making it nearly impossible for parents not to choose PODs. Modern work required too much. To raise a family and work became impossible. Humanity flourished because of those who worked. PODs further enabled this cultural norm by fostering children beyond what a normal upbringing could provide. Healthcare became obsolete as PODs covered everyone under eighteen, and the incredible results reduced costs over one’s lifespan.

Most parents only get eighteen summers with their kids. There’s terrible pressure to use that time perfectly. With PODs, that pressure dissipated. The weight of all the decisions no longer impacted a child’s entire life. No mistakes were made. The perfect simulation that real life could never offer.

That all happened fifteen years ago. In two days, on my son’s 18th birthday, he comes out of PODs.

October 8, 2091 - Central Park

I sit in my favorite spot in Central Park. A grass clearing beneath expansive trees. Large boulders shelter the clearing from the surrounding walking paths. This is my quiet place where all the memories come back. Real memories mixed with PODs memories. Where we used to have picnics. Wrestle in the grass. Play hide and seek amidst the trees. Search for treasure.

It used to be greener, but today there is a gray hue to everything. Gray like our apartment. Like my melancholy. Not just in the color but in feeling. It even smells gray, if that makes sense. Everywhere I go, the gray hue follows me. An emotional curtain before my eyes. A filter I can’t remove.

Three people appear through the trees. A woman - perhaps my age - and her two boys. Older, late teens. They stop and look in my direction. One of the boys points to the open greenspace in front of me and produces a frisbee. The other runs, glancing back, anticipating a toss. The other throws the frisbee. A beautiful glider. The other catches it not far from me.

The woman approaches and sits next to me.

“Mind if we join you?” she asks.

“No. Not at all.”

“This is our favorite spot. I usually read a book while my boys play.”

The boys toss the frisbee back and forth. A white alien saucer floating across the gray green expanse.

“When’s the day?” she asks.

“I’m sorry?”

“When does your kid get out of PODs?”

The question is a verbal bullet through my heart.

“How can you tell?”

“That look on your face would break a stone,” she says. “I can tell because my husband had the same look for years. We were part of the first test group. My oldest, Asher –” she points to one of the boys “– was a PODs kid.”

“That’s strange,” I say. “They told us we were the first test group.”

“That’s what they tell everybody. My husband went a bit crazy after Asher got out and dug that up.”

“How did he figure that out?”

“He hacked the labs. He was really good with computers.”

She looks away. I don’t ask where her husband is now.

She changes the subject back to me.

“When is your simulation done?”

“Tomorrow,” I say.

She leans towards me, places a hand on my shoulder. “Good luck. You’ll need it. But you’ll do fine. It’s hard, but my best advice is to pretend that none of it ever happened.”

“Did you not tell your kids?” I ask.

“No. What would I say?”

I try mapping out the conversation in my head. Dread fills me.

“How old?” I ask.

“Twenty and eighteen. Those two years with Asher being in PODs nearly killed us. Corey was our beautiful accident. We didn’t think we could have another. With the loss we felt with Asher, we kept Corey home.”

“Your youngest doesn’t know?”

“No.”

A bird sings behind us. A breeze carries the cold of Fall.

"I've spent so much of my life questioning," I say. An emotional cave opens inside me. The underworld now exposed.

"Questioning what?"

“If I did the right thing. If I've been doing the right thing.” The cave deepens. A new rift tearing open.

She turns to me. "You know," she says. "There's a lot of pressure on what to do. How we should do it. PODs seemed like an incredible benefit for those of us who felt we couldn't be with our kids. You regret doing it. But then wonder if you’d regret not doing it if you didn’t.” She gestures to the open grass. The laughter. The boys taunting one another. The frisbee flying back and forth. “We made choices. But here we are. Throwing frisbee in Central Park.”

One of the boys calls to her.

“I guess it’s dinner time,” she says. “Good luck tomorrow. We’ll be thinking of you.”

Before I can respond, she rises and walks away with her two boys.

Her last words stick with me.

Here we are. Throwing frisbee in Central Park.

October 9, 2091 - PODs Primary

3. Assimilation

My wife and I stand in the lobby. The same lobby of fifteen years ago. Gray white walls with a picture of a smiling child on each, perfectly centered and level. The same stale smell of rotting emotions.

My wife looks at me - truly looks at me for the first time in years - then reaches for my hand.

The door across from us opens. A man almost as tall as the door emerges. Smiling and with gray hair and beard. Glasses. He wears a white lab coat with an Incredible Hulk t-shirt underneath.

“Hi there,” he says. “You must be –” he looks from me to my wife and confirms our names. “I’m Dr. McGregor Kiin. I will help you and your son with the assimilation today.” He catches me looking at the Hulk t-shirt. “Oh,” he glances down, chuckles, then looks back at me. “It helps with the kiddos.”

My wife squeezes my hand. Let’s get on with this.

I take a deep breath. Kiin picks up on her silent signal.

“Let’s review the contract first,” he says, clasping his hands together in front of him. “You recognize that you are one of the first hundred couples to participate in the PODs program, and per your previous signatures you are sworn to secrecy. Sworn. To. Secrecy. What happens here remains here. The information is yours and that of your son. Talking about it outside these walls puts the integrity of the data - and your privacy - at risk. We use the information to improve future integrations, simulations, and assimilations. What you are about to see - and what you’ve been exposed to - cannot be shared outside of this room.”

My wife and I agree.

“Are you ready?”

“Yes,” I say.

Kiin’s smile broadens. It’s a genuine smile. Natural dimples. Yet I feel a sense of wrongness.

“Okay,” he says. “Wait right here.”

Kiin turns around and walks back to the door. Opens it, peeks inside - the smile never leaving his face - and whispers into the room beyond.

“Alright, come on out.”

Something is off. His tone of voice, or the way he’s looking behind the door.

Then our son walks out.

He’s three. Not eighteen. His same self we saw fifteen years ago. In his favorite orange long sleeve.

SUPER TRUCKS.

The glass of the world around me shatters.

My wife crumbles in a giant sob as our son runs up to us. The entire history of earth’s storms pouring out of her. And me. He looks at us like we have bugs crawling out of our ears.

“What’s wrong, Mommy?”

“I–” My wife can’t get the words out. “I missed you,” she says. Our son hugs our legs. We embrace him.

“You weren’t gone that long,” our son says.

I look up to Kiin, who’s smile hasn’t faded.

“For your son –” he says “– you were away for only a few hours.”

My insides shift as if I’m on a merry-go-round spinning at light speed.

“A few hours?”

He walks over as our son tells my wife about all the truck toys the doctors had in the broken, breathless excitement that only three year olds are capable of.

Kiin puts a hand on my shoulder.

“Your son was never in PODs. You were.”

I’m not able to process this.

“None of that happened?”

“No.”

“My God.” I choke up. “The woman I spoke to in Central Park?”

“Part of the simulation. It helps with the transition on assimilation days.”

A strange wave of relief. Horror. Happiness. Other feelings I can’t name.

“It’s going to take a while for this to fade,” Kiin says.

“I don’t understand.”

“You’ll eventually forget that this happened,” he says, waving his hands at the surrounding light green room. “But what you learned will remain. It won’t be conscious knowledge, but it will be there for you to leverage with your son.”

My wife and I are speechless.

“Does he know?” she asks, her words falling out like hail raining from the sky.

“He doesn’t,” Dr. Kiin says. “From his perspective, he took a quick nap then played with trucks for a few hours.”

“We experienced fifteen years in two hours?”

“Yes,” Kiin said. “You still have those eighteen summers.”

“Daddy! Mommy!” Our son pulls at our legs. “I have something else I need to tell you!”

“What’s that, buddy?” I say between tears that cry for the whole world.

“Can we get some ice cream?”

The old me would have hesitated. The simulated me.

But not this me.

“Yeah, big guy. Ice cream sounds amazing.”

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see how you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

For anyone curious on my writing process behind PODs, you can see it here:

https://arthurmacabe.substack.com/p/on-writing-pods

The twist! Really enjoyed this one.