Exploring Life through the Written Word

“You should be ashamed yourselves, mortified in the face of neighbors living round about! Fear the gods, my friends! Have some mercy on me in my own house!”

Dear friends,

Book 2 of Homer's The Odyssey marks a crucial turning point in the epic, transforming Telemachus from a passive youth into an active agent of his own destiny. Following Athena's inspiring visit in Book 1, the young prince takes his first independent steps toward manhood by calling an assembly and confronting the suitors who have invaded his home. This pivotal chapter explores themes of political authority, divine intervention, and coming of age, while establishing the moral framework for the epic's ultimate resolution.

This book captures the political sophistication and psychological realism of this transformative moment, as Telemachus transitions from a protected child to a potential leader. The book serves as both a political drama about community responsibility and a personal narrative about individual growth, demonstrating Homer's genius for weaving together public and private concerns into a unified artistic vision.

Book 2 opens with Telemachus rising at dawn, inspired by Athena's counsel from the previous evening. He arms himself with his father's spear—a symbolic assumption of inherited authority—and instructs the heralds to summon the Achaean lords to assembly. Significantly, this is the first such gathering in Ithaca since Odysseus departed for Troy twenty years earlier, highlighting both the political stagnation that has gripped the kingdom and the unique authority that Odysseus once wielded.

As the community gathers in the marketplace, Telemachus enters bearing his father's spear and accompanied by two faithful hounds. Athena enhances his natural charisma, causing the assembled men to marvel at his newfound dignity and presence. This divine assistance amplifies rather than replaces his own developing capabilities, establishing a pattern of collaboration between human effort and supernatural support that will characterize his journey.

The assembly begins with Aegyptius, an elderly lord, asking who has called the gathering and for what purpose. His assumption that the assembly concerns news of the army's return from Troy reveals how fixated the community remains on the absent warriors, making Telemachus's actual complaint all the more poignant.

Rising to address the assembly, Telemachus delivers his first major public speech—a crucial coming-of-age moment. He begins humbly, acknowledging his youth and inexperience while appealing to the assembly's protective instincts. The core of his complaint focuses on the suitors' destructive behavior: their daily slaughter of his livestock, consumption of his wine, and general waste of his father's accumulated wealth.

Crucially, Telemachus frames his grievance in terms that transcend personal injury. He argues that the suitors' violation of hospitality customs brings shame upon all of Ithaca and offends the gods who oversee such sacred relationships. This sophisticated rhetorical strategy demonstrates his growing political awareness and his understanding that effective leadership requires appealing to shared values and collective interests.

The young prince concludes with a direct appeal for community action, invoking both his father's memory and divine justice. His speech reveals not only his personal desperation but also his developing sense of moral responsibility and political authority.

The suitors respond through their two most prominent leaders: Antinous and Eurymachus. Their reactions reveal both their individual characters and their collective contempt for legitimate authority.

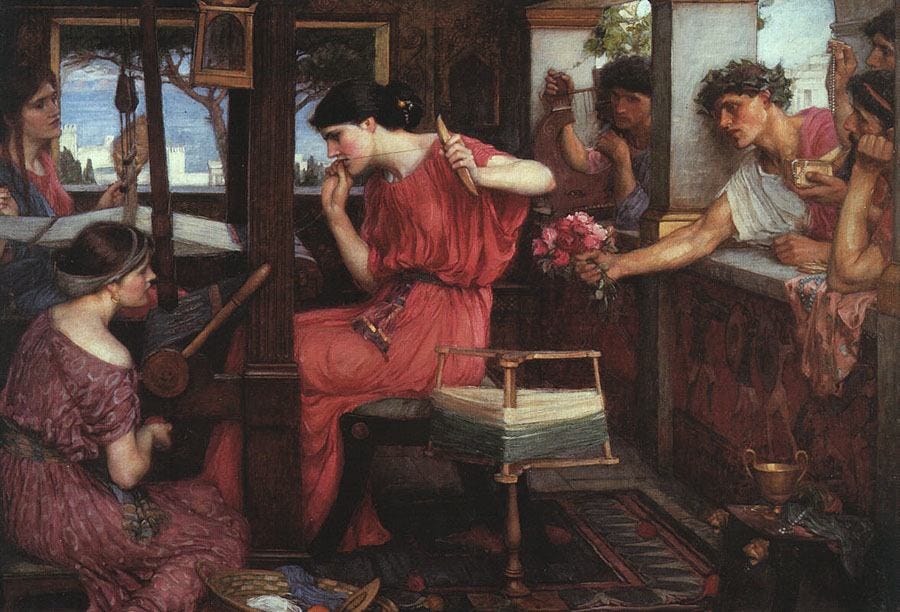

Antinous responds with open hostility, immediately deflecting blame onto Penelope. He recounts the famous story of her web—how she promised to choose a suitor upon completing a shroud for Laertes but secretly unraveled her work each night. His portrayal of her delay tactics as manipulative deception reveals his fundamental misunderstanding of her impossible situation and his complete disregard for the moral complexities she faces.

Eurymachus takes a more insidious approach, combining false sympathy with unreasonable demands. He acknowledges Telemachus's right to speak while ultimately reinforcing Antinous's position that Penelope must immediately choose a husband. His rhetorical sophistication makes him perhaps more dangerous than the openly hostile Antinous, as his apparent reasonableness might deceive those unable to see through his manipulation.

Both suitors demand that Telemachus compel his mother to remarry, effectively asking him to participate in the destruction of his own family's hopes. Their sense of entitlement and disregard for his legitimate authority as head of the household reveal the depth of their predatory opportunism.

At the climax of the assembly's tensions, Zeus sends a dramatic sign: two eagles appear suddenly in the sky, circle overhead, then tear at each other with their talons before flying away over the town. This divine intervention creates a moment of hushed awe among the assembled men, who recognize the significance of such an unusual occurrence.

Halitherses, an elderly seer and loyal advisor to Odysseus, interprets the omen as a prophecy of the hero's imminent return and a warning of severe consequences for those who oppose his family. His reading provides divine confirmation of what the audience suspects while establishing the moral framework within which subsequent events should be understood.

The suitors' response to this prophetic warning reveals their fundamental character flaws. Rather than showing appropriate reverence or even healthy skepticism, they respond with mockery and contempt. Eurymachus dismisses the omen entirely, arguing that many birds fly under the sun without carrying divine messages. This rejection of divine warning transforms them from mere antagonists into figures of tragic hubris who bring destruction upon themselves through their own choices.

Faced with the assembly's failure to act, Telemachus makes a final, reasonable appeal: he asks only for a ship and crew to seek news of his father, promising that if he learns of Odysseus's death, he will return and allow his mother to remarry. This proposal addresses the suitors' stated concerns while protecting his legitimate interests, but even this modest request meets with silence.

The community's inability or unwillingness to provide basic support forces Telemachus to seek alternative solutions. He retreats to the seashore to pray to Athena, who responds by appearing as Mentor, one of Odysseus's trusted advisors. Through this disguise, she provides practical guidance while maintaining the appearance of purely human assistance.

Mentor advises immediate action rather than further deliberation, emphasizing the need for secrecy and speed. Telemachus must secure a ship quietly and select a trustworthy crew to avoid interference from the suitors, who would certainly attempt to prevent his departure if they were to learn of his plans.

The final section focuses on Telemachus's careful preparations, revealing his growing competence and attention to detail. His involvement of Eurycleia, his old nurse, introduces questions about loyalty within the household while providing the secrecy necessary for his escape. Her initial distress at his plans reflects genuine concern for his safety, while her eventual compliance demonstrates deep loyalty to Odysseus's family.

Book 2 serves as a crucial chapter in Telemachus's transformation from passive youth to active hero. This development operates on multiple levels: physical, emotional, spiritual, and political. His assumption of his father's spear symbolizes his readiness to defend his family's interests, while his speech to the assembly marks his entry into public discourse as a legitimate political actor.

The divine enhancement of his natural charisma reflects ancient Greek beliefs about the relationship between legitimate authority and divine approval. However, Athena's assistance amplifies rather than replaces his own capabilities, suggesting that effective leadership requires both human effort and supernatural support. His growing frustration with political paralysis demonstrates emotional maturation, while his prayer by the seashore reveals developing spiritual awareness.

Homer presents a sophisticated understanding of the relationship between divine will and human responsibility. The gods provide guidance, inspiration, and opportunities, but mortals must still choose to act decisively. Athena's role throughout the book exemplifies this collaborative approach—she enhances Telemachus's abilities and creates favorable circumstances, but she cannot solve his problems for him.

The eagle omen represents a different type of divine intervention, providing information and warning rather than direct assistance. Its effectiveness depends entirely on human interpretation and response. The suitors' rejection of prophetic wisdom makes them conscious agents of their own destruction rather than unwitting victims of fate.

The assembly scene offers fascinating insight into ancient Greek political structures, revealing both democratic ideals and their practical limitations. Citizens gather as equals to discuss community concerns, but the assembly's ultimate failure to act demonstrates how the democratic process can be frustrated by entrenched interests and the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms.

The twenty-year gap since the previous assembly speaks to Odysseus's unique authority and the political vacuum his absence has created. The suitors represent aristocratic predation that threatens the foundations of civilized society, violating hospitality customs and property rights that held ancient communities together.

The competing speeches reveal different rhetorical strategies and their effectiveness. Telemachus employs logical argument, moral appeal, and invocation of shared values. Antinous employs deflection and blame shifting, while Eurymachus combines false sympathy with manipulation. Halitherses claims divine authority through prophetic interpretation.

These ancient examples of political rhetoric remain remarkably relevant to contemporary debates about truth, persuasion, and the responsibility of speakers and listeners in democratic discourse. The ease with which substantive grievances are displaced by personal attacks and irrelevant controversies reflects patterns that persist in modern political communication.

The Ithacan assembly represents primitive democratic elements that coexisted with monarchical authority in early Greek society. This combination of personal leadership and community participation would later evolve into more sophisticated democratic institutions, but the assembly's powerlessness reveals the limitations of democratic process without effective enforcement mechanisms.

The suitors' behavior exemplifies aristocratic competition that was endemic in ancient Greek society, where noble families regularly competed for political influence and economic advantage. Their collective predation on Odysseus's household represents this competitive dynamic taken to destructive extremes.

The systematic consumption of Odysseus's livestock and wine stores illustrates both the wealth-based nature of aristocratic power and the vulnerability of agricultural communities to predatory behavior. In ancient Greek economy, livestock represented multiple forms of value: immediate sustenance, raw materials, and long-term investment through breeding.

The violation of xenia (guest-friendship) threatens the reciprocal networks that facilitated trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange across the ancient world. The suitors' abuse of hospitality customs suggests recognition of no obligations beyond immediate self-gratification, making them unreliable partners in the complex web of relationships that held communities together.

Halitherses's interpretation of the eagle omen highlights the significant role that seers played in political decision-making, while the suitors' rejection underscores the dangers of impiety in a world where gods actively intervened in human affairs. The practice of augury—interpreting divine will through bird behavior—represents one of the oldest forms of religious divination.

Telemachus's prayer to Athena exemplifies the personal nature of divine-human relationships in Greek religion, where individuals could establish patronage relationships with specific deities. The suitors' impiety represents hybris that ancient Greeks considered extremely dangerous, making their eventual punishment both inevitable and justified.

The assembly's failure despite clear evidence of wrongdoing resonates with contemporary experiences of political paralysis and institutional capture. Telemachus's frustration with unresponsive political systems reflects the feelings of modern citizens when democratic institutions prove inadequate to address urgent problems.

The suitors' behavior parallels contemporary concerns about elite capture—how wealthy and powerful interests manipulate systems to serve their own interests at the community’s expense. Their systematic waste of resources while showing contempt for legitimate authority reflects patterns visible in various contemporary contexts.

The suitors' conspicuous consumption, which destroys productive capacity, parallels modern concerns about unsustainable economic practices that prioritize short-term gain over long-term stability. Their indifference to Ithaca's economic health reflects contemporary corporate short-termism and the prioritization of immediate profits over sustainable practices.

The rhetorical strategies employed in the assembly offer insights into contemporary debates about misinformation and manipulation of public opinion. Antinous's deflection tactics and Eurymachus's false reasonableness exemplify techniques central to modern political communication and social media manipulation.

The suitors' rejection of expert interpretation parallels modern tendencies to dismiss scientific evidence and professional expertise when they conflict with immediate interests or ideological commitments.

Telemachus's psychological journey offers insights into contemporary challenges of adolescent development. His struggle to assert independence while dealing with family trauma and social isolation reflects patterns relevant for modern young people navigating similar transitions. His recognition that he must act independently when adult authorities prove unreliable parallels experiences of many contemporary adolescents in situations where traditional support systems have failed.

Book 2 of The Odyssey serves as a masterful bridge between exposition and action while exploring themes that remain remarkably relevant to contemporary readers. Through Telemachus's first independent actions and the community's response, Homer creates a complex narrative illuminating fundamental questions about political authority, social responsibility, and individual moral development.

The young prince's transformation from passive victim to active agent reflects universal coming-of-age patterns that transcend historical boundaries. His recognition that institutional solutions may prove inadequate speaks to timeless challenges faced by individuals seeking positive change in resistant environments.

The political dynamics revealed in the assembly scene offer insights into both the possibilities and limitations of democracy. The community's failure to act illustrates how democratic ideals can be frustrated by entrenched interests and enforcement weaknesses—challenges that remain central to contemporary political discourse.

The suitors represent predatory opportunism that appears throughout history when traditional authorities weaken. Their systematic waste of resources, violation of social norms, and contempt for legitimate authority create behavioral patterns resonating with contemporary concerns about institutional corruption and unsustainable practices.

Perhaps most significantly, Book 2 establishes the moral framework within which subsequent events should be understood. The divine signs, prophetic warnings, and clear distinctions between just and unjust behavior create expectations about eventual resolution that will guide readers through the complexities ahead.

For contemporary readers, the book offers rich material for considering connections between ancient and modern experience. The themes invite reflection on personal responsibilities as citizens, family members, and moral agents in contexts that may differ in detail but share fundamental structural similarities with Telemachus's situation.

1. How does Telemachus's calling of the assembly and his speech demonstrate his emerging leadership qualities? What does the twenty-year gap since the previous assembly suggest about political authority and institutional maintenance?

2. Analyze the relationship between Athena's assistance and Telemachus's own efforts throughout Book 2. How does the eagle omen function in the narrative, and what does the suitors' rejection of Halitherses's interpretation reveal about their characters?

3. Which aspects of Telemachus's situation do you find most relevant to contemporary life? Consider themes of institutional dysfunction, generational conflict, and the challenges of moral leadership. What lessons might modern readers draw from his approach to confronting injustice when traditional authorities fail to act?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 3. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is titled King Nestor Remembers and spans pages 107-123. In the Wilson translation, this chapter is titled An Old King Remembers and spans pages 135-151.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription costs only $12 per year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I agree with the prior comments about how difficult it is add anything intelligent to Matthew's essay. Just a couple of random observations: The scene where the suitors cavalierly reject the interpretation by Halitherses of the eagles was particularly powerful to me. When villains disregard advice or prophesies from wise elders, you know they will get their comeuppance. And the ending scene, where Telemachus sets sail, uses vivid detail to convey a strong sense of adventure and anticipation for what lies ahead in the story.

The themes in the Odyssey (greed, gross disregard for cultural traditions, violations of the norms of human decency, coming of age of a charismatic leader to set the world right) are universal and timeless. We can certainly seem them in modern literature and life.

Obviously the subject of the Odyssey is Odysseus, but I’m enjoying the scene setting for Telemachus’s growth.

When previously starting the book I’ve always written him off as a bit of brat (especially in the way he talks to Penelope). Your aframing of his development in this write up has peaked my interest for the rest of the story