Exploring Life and Literature.

"You—your mind is always churning out new intrigues! I can't bear you anymore!"

Dear friends,

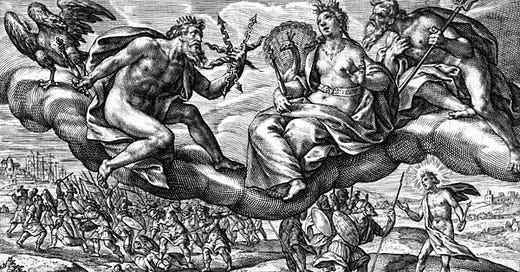

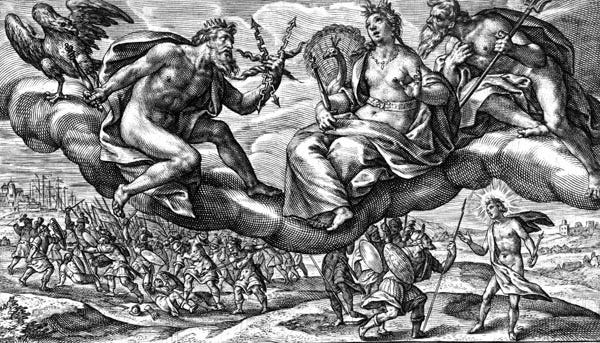

Book 15, "The Achaean Armies at Bay," is a pivotal turning point in this ancient war poem. It serves as a dramatic reversal of fortune, revealing both the unpredictable sway of divine will and the cost of defiance. The book begins in the aftermath of Zeus’ absence. In Book 14, Hera, ever cunning, seduced the king of the gods into sleep, giving the Greeks a much-needed advantage in the war. But her triumph is short-lived. Zeus awakens with fury, and the heavens tremble with his wrath.

He turns to Hera, demanding to know who orchestrated this deception. Hera, caught but defiant, answers with measured cunning. She deflects blame, claiming it was Poseidon who disobeyed Zeus by intervening in battle. It is true, of course—Poseidon had entered the fray to support the Achaeans, tipping the scale against the Trojans while Zeus lay asleep. Now awake and vengeful, Zeus commands Hera to summon Iris, the swift-footed messenger, and Apollo, the far-shooting god, to his side.

Zeus lays out his plan. He sends Iris to order Poseidon to withdraw from the battlefield immediately. Though Poseidon resents the command, feeling himself equal to Zeus in dignity (if not in power), he eventually yields, submitting to the cosmic order. Meanwhile, Zeus instructs Apollo to rejoin the Trojans and reinvigorate Hector, who had recently been wounded and forced to retreat.

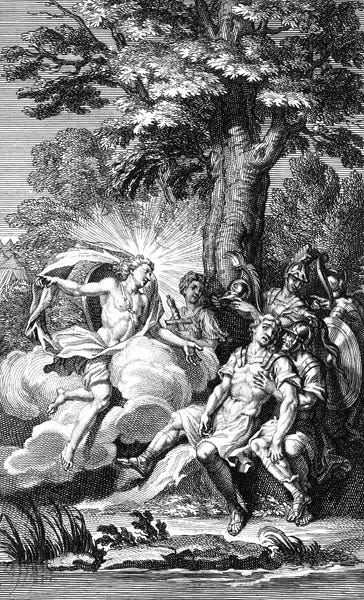

This divine reshuffling of power marks the beginning of a relentless Trojan assault. Apollo descends to Hector, breathing divine strength back into the warrior’s body. Hector rises like a god, radiant and unstoppable, rallying his troops with renewed energy. The tide of battle shifts violently.

The Trojans launch a furious attack, and the Achaeans—still reeling from internal strife, injuries, and exhaustion—begin to falter. One by one, the Greek heroes are either wounded or pushed back. Ajax the Greater, one of the mightiest Achaeans, puts up a monumental defense, standing like a wall between the Trojans and the Achaean ships. But even Ajax cannot hold forever against gods and men combined.

As the Trojans storm the Achaean ramparts and bear down upon the ships, the desperate cries of the Greeks fill the air. Nestor, the wise elder, and other generals attempt to maintain order, but chaos is mounting. Patroclus, the beloved companion of Achilles, appears briefly, rushing to tend to the wounded Eurypylus. Achilles, however, remains apart from the battle, still nursing his grudge against Agamemnon for the insult done to him earlier in the poem.

Hector, with Apollo by his side, leads the Trojan charge to the ships. The Greeks are now in dire straits. The battle is no longer about honor or glory—it is about survival. Book 15 ends on the brink of catastrophe, as the Trojans prepare to set fire to the Achaean ships, an act that would destroy their only means of retreat.

A recurring theme throughout The Iliad—but incredibly potent in Book 15—is the power of the gods to shape human destiny. Zeus is portrayed here not merely as a distant overseer but as an active manipulator of fate. His will is absolute, and when thwarted, as it was in Book 14, the universe itself trembles in response. His awakening sets off a cosmic rebalancing that has immediate and devastating consequences for the mortal world.

Yet even Zeus’ dominance is challenged. Poseidon's resistance, though ultimately suppressed, reminds us of the tension that simmers beneath the surface of divine authority. The gods in The Iliad are not united—they are petty, proud, and emotional. Their squabbles mirror those of the mortals below. Hera’s deceit, Apollo’s favoritism, and Poseidon’s pride all contribute to a sense of divine chaos, a pantheon whose conflicts ripple through the lives of men.

This divine dysfunction makes the fate of the mortals all the more tragic. The Greeks and Trojans are pawns in a game they cannot fully understand, let alone control. Even the greatest warriors—Ajax, Hector, Achilles—are subject to the whims of higher powers.

The human cost of this divine game is staggering in Book 15. As the Trojans advance under Hector’s leadership, countless Achaeans fall. There is an air of desperation among the Greeks that is noticeably different from that in earlier books. The confident, orderly Achaean army is now scattered and scrambling. Their leaders are wounded, their morale shattered.

Ajax, ever the stalwart defender, emerges as a tragic figure in this book. His bravery is undeniable, his strength unmatched. But even Ajax cannot hold back the tide alone. His stand before the ships is a feat of almost superhuman resolve, but it is clear that he is fighting a losing battle. The image of Ajax covered in sweat and gore, holding his massive shield as the only barrier between the Trojans and the burning ships, is one of the most striking scenes in the poem. It captures both the nobility and futility of heroism in the face of overwhelming odds.

Meanwhile, the tension between Achilles and the rest of the Achaeans continues to loom in the background. Though he does not appear directly in the battle of Book 15, his absence is felt acutely. The Greeks need him, and they are aware of it. However, Achilles is still locked in his prideful isolation, unwilling to return to battle even as his comrades fall. The seeds of Patroclus’ eventual intervention are sown here—an act that will change the course of the war and the epic itself.

While the events of Book 15 are steeped in myth and legend, they resonate deeply with modern readers because they speak to enduring aspects of the human experience. At its core, this chapter examines what happens when institutions fail, when leaders are compromised, and when those at the bottom bear the consequences of decisions made far above them.

The gods in The Iliad are often compared to powerful political or economic forces in the modern world—forces that shape the lives of ordinary people in ways that are invisible, arbitrary, and often cruel. Zeus’ decision to back the Trojans is not based on justice or morality but on a plan he has crafted to restore balance in the cosmos. It mirrors how modern individuals often feel at the mercy of decisions made in boardrooms or government chambers—places far removed from the battlefield of everyday life.

Poseidon's reluctant submission, Hera’s manipulation, and Apollo’s intervention can be likened to the internal power struggles within institutions, where ambition and rivalry override the needs of the people. The Achaeans, left to suffer the consequences of divine meddling, reflect the plight of modern societies caught in the crossfire of global conflict, economic downturn, or political upheaval.

Moreover, the theme of pride and its consequences remains powerfully relevant. Achilles' refusal to fight, Agamemnon's earlier insult, and Hector's overconfidence all point to the destructive power of ego. In a world still grappling with the effects of polarized politics, international conflict, and fractured leadership, The Iliad remains a sobering reminder that pride unchecked can bring civilizations to the brink.

The most moving aspect of Book 15 is the endurance of the human spirit amid chaos. Despite the gods’ interference, despite their own leaders' failings, the Achaean soldiers continue to fight. Ajax’s stand is a powerful testament to human courage. He knows he cannot win. He knows the gods have abandoned him. But still, he fights—not for glory, but to protect his comrades, to hold the line just a little longer.

In this, we see the timeless heroism of those who persist even when hope seems to fade. In modern times, such resilience is exemplified by the firefighters of 9/11, the nurses during pandemics, and the civilians who rebuild after war. These are not mythic warriors but ordinary people doing extraordinary things under impossible pressure. Ajax, in his moment of crisis, becomes a symbol of all who fight because it is right—even when the gods have turned away.

Book 15 does not end with a resolution but with suspense. The Achaeans are driven to the edge, and the ships are about to be torched. The consequences of divine anger and human stubbornness converge into a single moment of peril. And though we know that Achilles will eventually return and that the tides will shift again, the pain of this chapter lingers.

It is a portrait of a world out of balance—where the powerful are distracted or vengeful, and the ordinary pay the price. It is also a portrait of endurance, of men who hold the line despite everything.

In our age of uncertainty—whether through political division, global pandemics, climate crises, or the dislocation caused by technological change—The Iliad, and especially Book 15, continues to echo across time. It reminds us that power is fragile, that pride is dangerous, and that the most heroic acts often come in the darkest hour, when all seems lost.

"Apollo breathed enormous power into Hector, and he came alive, his senses filled with drive..."

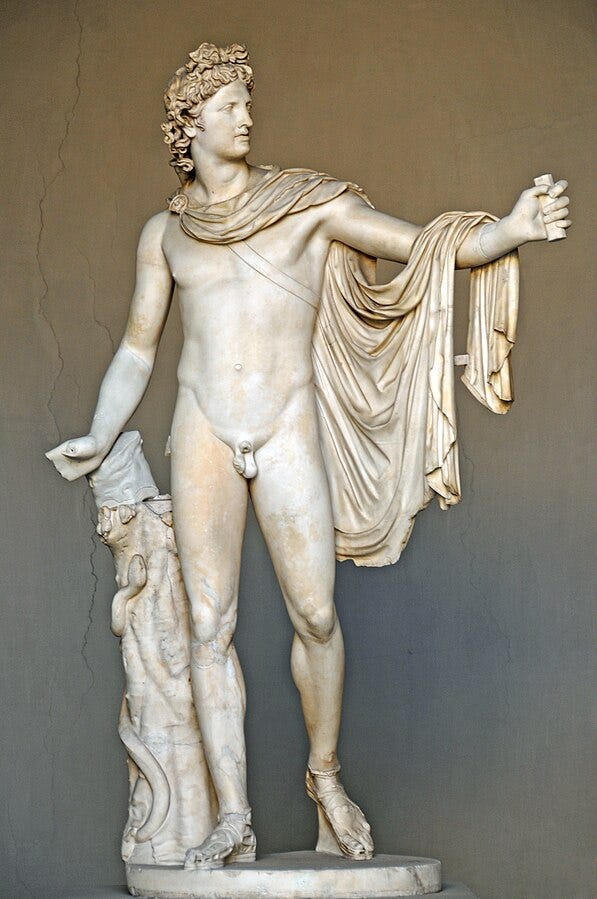

Among the pantheon of Greek gods, few figures shine as brightly or as complexly as Apollo—the god of light, prophecy, music, and medicine. His mythological presence is as radiant as the sun he governs, yet beneath the gleaming surface lies a deity both divine and deeply human. Apollo stands at the intersection of intellect and passion, order and chaos, reason and madness—a paradoxical figure who, despite his celestial origin, reflects the contradictions and yearnings of humanity. To understand Apollo is not only to glimpse the divine in Greek mythology but also to uncover timeless truths about power, beauty, and the fragile pursuit of harmony in a disordered world.

Apollo’s origins stretch deep into the ancient Indo-European past, with some scholars suggesting that his name may even predate the Mycenaean civilization. Early references to him appear in Linear B tablets from the 13th century BCE, possibly under the name Apellon. By the time of Homer in the 8th century BCE, Apollo was already a fully developed deity, prominent in myth, religion, and poetry.

His cults proliferated across the Greek world, with major centers of worship at Delos, his mythic birthplace, and Delphi, the site of his most renowned oracle. Apollo’s arrival at Delphi, where he slew the Python and claimed the sanctuary as his own, signals more than a mythic victory; it represents a civilizing force supplanting older, chthonic religions tied to the earth and primal chaos. In this, Apollo emerges as a god of clarity and reason, a patron of law, structure, and enlightenment in contrast to the ancient chaos he supplants.

The Greeks saw Apollo not merely as a god to be worshipped but as an ideal to be aspired to. His aesthetic—youthful, athletic, luminous—was mirrored in Greek art, where he often appears as the epitome of kouros, the beautiful young man. His influence also extended to civic and political life. Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, for example, was central in guiding significant decisions, from colonization to war, making him a god of both statecraft and spirituality.

Apollo is one of the twelve Olympians, the son of Zeus and the Titaness Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. While many gods in the Greek pantheon represent domains that are finite or limited—Poseidon rules the sea, Demeter the harvest—Apollo’s reach is strikingly vast and abstract. He governs music and poetry, prophecy and healing, archery and plague, civilization and order. He is, in many ways, the embodiment of the Greek ideal: sophrosyne—a balanced harmony of body, mind, and spirit.

Yet, Apollo’s position among the gods is not without tension. His relationships with other deities are marked by rivalry and pride. He frequently clashes with Hermes, who, as a baby, steals Apollo’s cattle, and with Eros, who, in retaliation for a slight, causes Apollo to fall hopelessly in love with the nymph Daphne. These stories remind us that even Apollo, radiant and rational, is not immune to folly or failure. His divine status does not exempt him from jealousy, heartbreak, or humiliation.

Apollo’s duality is further revealed in his associations with both healing and disease. As the god who can bring plague with his arrows—as he does in The Iliad—Apollo is a destroyer. But as the father of Asclepius, the god of medicine, he is also a restorer of life. These contradictions are not flaws but functions of his complexity. Apollo, like life itself, offers no easy answers.

Apollo’s literary appearances are numerous and varied, but perhaps his most famous role is in Homer’s The Iliad, where he plays a crucial, if enigmatic, part. The epic opens with Apollo sending a plague upon the Greek army in punishment for Agamemnon’s insult to his priest, Chryses. This act not only establishes the divine stakes of the poem but also casts Apollo as a god deeply concerned with honor and justice, even at the cost of human suffering.

Yet, Apollo’s sense of justice is not always impartial. He supports the Trojans out of loyalty to Hector and others, often acting as a counterforce to Athena and Hera, who champion the Greeks. This alignment reveals Apollo’s willingness to take sides and to act emotionally—qualities that remind us of the capriciousness of the gods and the fragility of mortal endeavors.

In the Homeric Hymns, Apollo is celebrated as both a newborn and an eternal force. The Hymn to Apollo recounts his birth on Delos and his arrival at Delphi, where he establishes his oracle and receives homage from all of Greece. Here, Apollo is depicted not only as a god of power but of refinement—a bringer of the lyre, the dance, and the spoken word.

Tragedians also found in Apollo a fertile subject. In Aeschylus’s Oresteia, he is the divine advocate for Orestes, guiding him to justice and defending him before the court of Athens. Apollo thus becomes an agent of rationality, promoting trial by jury over cycles of blood vengeance. This portrayal underscores his role in the Greek imagination as a harbinger of civilization and lawful order.

Apollo’s strengths are unmistakable: he is beautiful, wise, artistic, prophetic, and just. His music can charm gods and men alike, and his foresight allows mortals to glimpse the shape of their fate. As a god of balance, he offers a path away from chaos—a sunlit guide through the shadows of uncertainty.

Yet these strengths are often accompanied by flaws that render him strikingly human. Apollo is prideful, easily offended, and sometimes unmerciful. His love affairs almost always end in disaster. He falls for Daphne, who transforms into a laurel tree to escape him; for Cassandra, who spurns him and is cursed never to be believed; and for Hyacinthus, whose death is both a tragic loss and a testament to Apollo’s inability to protect what he loves. Love, for Apollo, is often possessive, idealized, and destructive.

These weaknesses make Apollo a god of intense contradictions: he inspires both healing and harm, wisdom and irrationality. He is a figure who strives for harmony but is often undone by his passions. In this, he resembles not the omnipotent gods of monotheism, but a deeply flawed hero—capable of greatness, but vulnerable to the very forces he seeks to master.

Apollo may be an ancient god, but his relevance endures. In an age increasingly defined by technological advancement and information, Apollo’s attributes—reason, clarity, foresight—are more vital than ever. He represents the human aspiration toward knowledge and control, the desire to illuminate the world through logic, science, and art.

Yet his story also cautions against hubris. Apollo’s tragic flaws—his pride, his possessiveness, his failure to understand the limits of his power—are eerily familiar in a modern world where technology often outpaces wisdom and progress can come at the cost of empathy. His myths serve as reminders that reason without compassion, foresight without humility, can lead to ruin.

In literature and philosophy, Apollo often serves as a symbol of the rational mind, set in contrast to Dionysus, god of wine and ecstasy. Nietzsche famously explored this dichotomy in The Birth of Tragedy, suggesting that true art arises from the tension between these two forces: the ordered and the chaotic, the reasoned and the passionate. In this light, Apollo is not a solitary ideal but one half of a necessary whole.

Even in popular culture, echoes of Apollo persist. He appears in science fiction, as seen in Star Trek, where the spaceship Apollo confronts modern humanity; in poetry and film, he often serves as a metaphor for vision and order. His influence spans not only time but also genre, proving that the myths of the past continue to shape the questions of the present.

To study Apollo is to walk a path of paradox—toward light, but through shadow; toward reason, but with passion; toward the divine, but through the deeply human. He is a god of aspiration and limitation, a figure who both reveals and conceals the mysteries of existence. His arrows bring plague, but his lyre brings healing. He is the seer who cannot always save, the lover who cannot always hold.

And yet, he endures. Not because he is perfect, but because he reflects our struggle to be whole. Apollo is the golden thread between gods and mortals, a radiant symbol of what it means to strive for beauty, truth, and harmony in a world that offers none of these freely. In his triumphs and his failures, we find a mirror—not just of ancient belief, but of our eternal longing to bring light into the dark.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

What is Apollo’s role in Book 15, and how does it contrast with the roles of other gods?

What do the interactions between the gods reveal about their personalities and relationships?

What does the destruction of the Achaean rampart by Apollo symbolize?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 16. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Patroclus Fights and Dies and covers pages 412-441. In the Wilson translation, it is called Love and Death and covers pages 379-409.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

And I have a tip jar available for those who prefer. Thank you very much.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Hi fellow readers,

I only joined this read a week ago, so have had a lovely Easter catching up with both the reading itself, and the weekly emails, which are very useful, thanks Matthew. I particularly like the character summary that you do at the end.

I last read both poems at University 40 years ago, as a 17 year old partying her way through a Bachelor of Arts, so I have no real memory of them. I had the Wilson sitting on my shelf and then saw this read listed on Footnotes & Tangents, so decided to join.

I also thought I’d share a book I ordered last night, which some may be interested in. It’s called “Mythica, a new history of Homer’s world, through the women written out of it’ by Emily Hauser, a British classics scholar. I am interested in having some focus on the women in the poems, as I read.

Anyway, thought I’d pop in and say hello, and I’m looking forward to continuing this journey 😊

Clearly, humans have little if any to say about their own condition, except to the extent that the gods are fickle and be made grumpy. It's hard to say that there is any such thing as "fate" or "destiny" when the gods can change their mind at any moment and even then bicker among themselves, but regardless we all know where the power lies.

I'm not going to lie, with this chapter I'm starting to feel a little battle fatigue. Book after book, their fighting spirits and fury keep getting roused seemingly more and more, like they're now at 234% effort? I'm still enjoying it, but it's page after page of new names felled along with their missing body parts! I could use a change of pace. :)