Exploring Life and Literature.

“I have no taste for food—what I really crave is slaughter and blood and the choking groans of men!”

Dear friends,

Book 19 of The Iliad is a moment of somber resolution, a calm before the storm of violence that will soon return to the battlefield. Following the emotional power of Book 18—where Achilles grieves for Patroclus and receives new armor crafted by Hephaestus—this chapter offers a different sort of intensity. Achilles finally reconciles with Agamemnon and prepares to return to war, but the tone is filled with fatalism and focused determination. This is the book of readiness: readiness to fight, to mourn, and to die.

The book opens with Thetis, Achilles’ divine mother, bringing the magnificent armor to her son. The moment is visually and emotionally arresting. Achilles, still stricken by grief, is transformed into something nearly otherworldly as he dons the armor—an image of fire and glory and impending death. Homer describes the new shield and armor as god-forged, radiant, and terrifying, signifying that Achilles is not just preparing for battle—he is preparing to fulfill his destiny.

After receiving the armor, Achilles calls a full assembly of the Achaeans. He announces his return to the war, and in a critical narrative development, he and Agamemnon reconcile. Their conflict, which began in Book 1 and sparked Achilles’ withdrawal from the war, is now resolved. Agamemnon acknowledges that he was wrong to take Briseis, Achilles’ war prize, and attempts to make amends by offering gifts, including treasure and the return of Briseis herself.

Achilles, however, is unmoved by material compensation. His grief for Patroclus and his awareness of his impending death have changed his values. He refuses the feast offered in celebration of the reconciliation and insists on returning to battle immediately. His reasoning is simple and devastating: his beloved friend is dead, his own life is nearly over, and nothing else matters now except revenge.

Odysseus, always the pragmatist, convinces Achilles to allow the troops to eat before going to war, knowing they will fight better with strength. While the men eat, Achilles continues to fast, another sign of his separation from the world of the living. His abstention from food is both symbolic and literal: he is already moving into the realm of the dead, bound by grief, rage, and purpose.

Meanwhile, Briseis is returned to Achilles. In a touching and unexpected moment, she mourns Patroclus, revealing that he had comforted her gently in her captivity. This passage adds further depth to Patroclus’ character, but it also humanizes Briseis, often treated as a mere prize. Her sorrow links her more intimately to Achilles’ loss and gives her a voice within the tragic chorus.

The book concludes with the arming of Achilles, a detailed and awe-inspiring description that mirrors the warrior’s internal transformation. As he mounts his chariot, he speaks to his immortal horses, urging them to bring him back from battle. But one of the horses, gifted with speech by Hera, responds ominously: Achilles will return this time, but not for long. His death is near.

This moment seals Book 19 as one of both action and anticipation. Achilles is ready, not just to fight, but to embrace the end.

Book 19 of The Iliad is a masterpiece of transition. It completes Achilles’ shift from angry isolation to tragic engagement, resolving the personal conflict that opened the epic and preparing the ground for the final battles. But more than just a narrative pivot, it is a chapter rich in symbolic depth, emotional weight, and existential inquiry.

First and foremost, Book 19 explores the theme of reconciliation. The meeting between Agamemnon and Achilles could have been a simple plot device, but Homer imbues it with complexity. Agamemnon tries to excuse his past actions by blaming Zeus, Fate, and the Furies—a classic attempt to displace responsibility. Achilles responds with terse acceptance, focused more on the future than the past. This exchange raises important questions about the nature of apology and forgiveness. Is Agamemnon truly sorry, or merely politically expedient? Is Achilles forgiving, or simply too broken to care?

In modern terms, this moment resonates with how we understand leadership, accountability, and the politics of reconciliation. In both personal and public life, the ability to own one’s mistakes and the decision to forgive or move on are deeply human challenges. Achilles’ refusal to feast or celebrate his return underlines that some wounds cannot be healed with gifts. Honor, once broken, can only be repaired through action—and sometimes not even then.

Another key theme is transformation. Achilles’ donning of his new armor is more than a warrior preparing for battle—it is a metamorphosis. The armor is divine, signaling that Achilles is no longer fully human. His grief has elevated and isolated him. He has become an avenger, a symbol of wrath and justice, but also of sacrifice. In literature and psychology alike, armor often represents the persona—the outward identity we construct to survive the world. For Achilles, the new armor covers a soul hollowed by loss, suggesting that what makes him heroic is not just his strength, but the burden he carries.

This metaphor is especially poignant today. In modern life, we too wear armor: emotional detachment, sarcasm, busyness, social personas. Many people, like Achilles, return to their duties and routines with grief still fresh, invisible beneath the surface. His refusal to eat, to rejoin the world, is emblematic of the numbing effects of trauma and the ways grief can alter our relationship with everyday life.

Briseis’ lament is another powerful moment of emotional resonance. Though often silent or sidelined in the epic, here she grieves not for herself, but for Patroclus—a man who treated her with compassion in a brutal world. Her voice adds dimension to the male-dominated narrative and reminds us of the human cost behind the glory of war. In today’s context, Briseis symbolizes the marginalized, the voiceless, the people whose stories are often lost amid larger struggles. Her grief makes the epic more inclusive, even if only momentarily.

Perhaps the most haunting moment in Book 19 comes at the end, when the horse speaks. This miraculous intervention reminds the reader that fate cannot be evaded, even by a man as powerful as Achilles. The prophecy that he will die soon casts a shadow over his every movement. It is not the threat of death that haunts Achilles, but its certainty. He does not seek to avoid it—he marches toward it.

This fatalism is central to the epic's moral universe. For the ancient Greeks, fate was an inescapable force, and true greatness lay in meeting it with courage. In modern life, we may not believe in fate in the same way, but we confront our own versions of inevitability: aging, illness, injustice, grief. Achilles’ choice to act meaningfully, even knowing the end, speaks to the human need to make our time count. His actions are not merely reactions—they are assertions of will in the face of mortality.

Book 19 also illustrates the tension between the personal and the collective. Achilles’ return is not just a personal decision—it shifts the entire trajectory of the war. His presence restores morale, strengthens the Achaeans, and strikes fear into the Trojans. In times of crisis—whether war, social upheaval, or loss—one person’s decision can ripple outward. Achilles becomes a symbol of both hope and doom. His re-entry into the battle is both a rescue and a foreshadowing.

Finally, Book 19 is deeply concerned with time—the time we have, the time we lose, and how we choose to spend it. Achilles’ urgency, his refusal to feast, his impatience with ritual, all stem from an awareness that his time is almost over. In a culture like ours, often consumed with productivity, future plans, and long-term goals, Achilles reminds us that sometimes the most honest response to loss is to act now. To love now. To grieve now. To be present now.

The Warrior’s Resolve

Book 19 of The Iliad is not a chapter of grand spectacle—it is a chapter of emotional clarity and quiet power. Achilles does not fight in this book, but he prepares. He readies himself not just for battle, but for death. He puts aside his pride, makes peace with his enemies, honors the dead, and steels himself to fulfill his fate.

In doing so, he becomes more than a warrior. He becomes a symbol of what it means to live meaningfully under the shadow of loss. His story, far from being an ancient relic, is a mirror held up to our own struggles: with grief, with forgiveness, with purpose.

In the end, Achilles teaches us not just how to fight, but how to feel—and how to move forward even when our hearts are broken.

“We will bring you back still—alive this time— but not for long. The hour of your death is near at hand.”

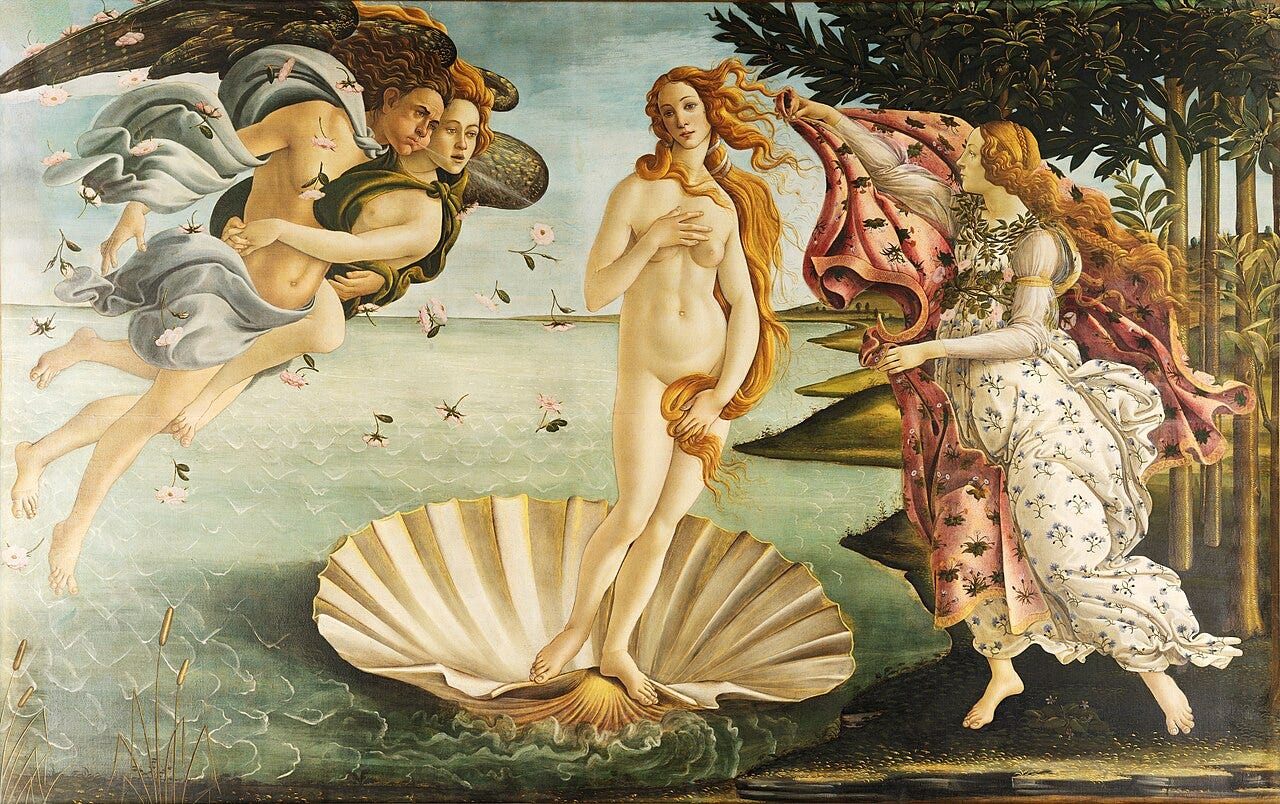

A Goddess Born from the Sea

Among the pantheon of Greek deities, Aphrodite stands out as one of the most compelling and contradictory. She is the goddess of love, beauty, desire, and fertility—yet her mythic narratives are marked by war, jealousy, and power struggles. She is both revered and feared, her influence as seductive as it is disruptive. In the ancient world, Aphrodite represented the irresistible force of attraction that could bind gods and mortals alike. In the modern world, she continues to symbolize the complexities of love, sexuality, and self-image.

Aphrodite is not simply a divine ideal of feminine beauty. She is a goddess whose mythology reveals the ancients' understanding of the emotional and erotic bonds that shape society. From her mysterious birth to her tumultuous affairs, Aphrodite offers a rich lens through which we can examine how cultures have interpreted the power of love—not as a passive emotion, but as a dynamic, even dangerous force.

To explore Aphrodite is to engage with the deepest currents of human experience: longing, connection, jealousy, and the pursuit of transcendence through beauty.

Origins and Historical Context

The origins of Aphrodite are layered and, like many mythological figures, rooted in older, pre-Greek traditions. Her identity as a love goddess has parallels in earlier Near Eastern deities such as the Mesopotamian Inanna and the Phoenician Astarte. These goddesses, too, embodied love, fertility, and war, suggesting that Aphrodite emerged from a broader cultural matrix where the feminine divine held immense, often ambivalent power.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, one of the earliest sources for Greek mythology, Aphrodite is born from the severed genitals of Uranus, the sky god, cast into the sea by his son Cronus. From the sea foam (aphros), she rises fully formed near the island of Cyprus—a miraculous birth that marks her as elemental, not the daughter of any mother, but of sky and sea. This version of her origin emphasizes her primordial, pre-Olympian nature. She is older than Zeus, older than order, and her domain—desire—remains beyond the governance of reason.

Other accounts, such as those found in Homer’s Iliad, describe her as the daughter of Zeus and Dione, making her an Olympian goddess by birth. This duality of origins—divine yet disruptive—mirrors her role in myth: she belongs within the pantheon, yet her influence often throws the divine and mortal worlds into chaos.

In Greek culture, Aphrodite was worshipped widely, especially in coastal cities such as Cyprus and Corinth. Her cult included both fertility rituals and sacred prostitution, reflecting her dual role as a goddess of erotic love and generative power. At the same time, her domain extended to marriage, diplomacy, and even death, as her presence was believed to guide the soul into the afterlife.

Aphrodite in Ancient Literary Works

Aphrodite appears prominently in many of the foundational texts of Western literature, where her influence is both thematic and direct. In Homer’s Iliad, she plays a crucial role in the events leading up to and during the Trojan War. It is Aphrodite who promises Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, to Paris in exchange for his judgment in a divine beauty contest. This act sets in motion a decade-long war, thousands of deaths, and the eventual fall of Troy.

In the epic’s battlefield scenes, Aphrodite appears to protect her son Aeneas, only to be wounded by the mortal warrior Diomedes. This moment is striking not only for its violence but for its depiction of a goddess exposed—bleeding and humiliated. It reveals the tension between Aphrodite’s divine status and her vulnerability. Unlike Athena or Artemis, Aphrodite is not a goddess of war, yet her influence on the causes of war is profound.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, as mentioned, her birth from the sea establishes her as an ancient and elemental force. She is not only beautiful but also fearsome—a reminder that love, when unleashed, is as destructive as it is divine.

Aphrodite is also central to Sappho’s poetry. The lyric poet from the island of Lesbos invokes her frequently, asking for help in matters of love and heartbreak. Sappho’s “Hymn to Aphrodite” presents the goddess not as distant and cold but as tender, attentive, and responsive to human suffering. In this context, Aphrodite is both powerful and intimate—a companion in the most private emotional realms.

Perhaps most significantly, in Roman literature, Aphrodite becomes Venus, the divine mother of Aeneas, founder of Rome. In Virgil’s Aeneid, she is depicted as both protective and political, guiding her son toward his destiny. Here, love becomes legacy, and the personal becomes historical.

Analysis of Aphrodite as a Goddess

Aphrodite defies simple categorization. She is often seen as the embodiment of sexual beauty, but this interpretation only scratches the surface. Her myths and literary appearances show her wielding influence over gods and mortals alike, suggesting that her true domain is the power of attraction—whether romantic, erotic, or aesthetic.

Unlike other Olympian deities who govern through force, wisdom, or law, Aphrodite rules through desire. Her power is subtle yet overwhelming. She does not need to fight to win; her presence alone alters the course of events. Yet this power is not without consequence. In myth after myth, Aphrodite’s interventions lead to jealousy, rivalry, and sometimes ruin. She is the patroness of both love and lust, both creation and conflict.

Her relationship with other gods is revealing. She is married to Hephaestus, the crippled god of the forge, but has an ongoing affair with Ares, the god of war. This triangle—beauty, labor, and violence—reflects the broader tensions in society about the roles and expectations of women, marriage, and desire. Her unfaithfulness is not treated as mere scandal; it is symbolic of love’s refusal to be confined by duty or order.

Yet Aphrodite also has moments of tenderness and protection. Her care for Aeneas, her weeping over Adonis, and her gentle presence in Sappho’s poems reveal a goddess who understands the ache of longing. In this way, she is more than a figure of seduction; she is a divine recognition of the soul’s yearning for union, for connection, for beauty that transcends the material.

The Goddess Among Us

Aphrodite remains deeply relevant in the modern world, where questions of love, beauty, identity, and desire continue to shape human experience. In a society obsessed with appearance, consumerism, and sexual expression, the figure of Aphrodite both mirrors and challenges our assumptions.

On one hand, Aphrodite has been co-opted by modern media and advertising as a symbol of superficial beauty and sexual allure. Her image is invoked in everything from cosmetics to fashion, reinforcing the idea that physical perfection equals power. But this is a limited reading. The true Aphrodite is not just about appearance—she is about emotional gravity, relational magnetism, and the deep, often chaotic need to be desired and to desire.

Aphrodite is also a symbol of empowerment. In reclaiming sexuality, especially among women and marginalized groups, the goddess stands as a figure of autonomy and agency. Her unapologetic embodiment of passion challenges puritanical and patriarchal norms. She owns her desires, initiates her lovers, and shapes destinies—not in service of others, but on her own terms.

At the same time, Aphrodite’s myths caution us about the double edge of love. Her stories remind us that attraction can be manipulative, that beauty can be blinding, and that desire can undo reason. In a digital age of curated images and algorithmic matchmaking, Aphrodite whispers an ancient truth: love is never just surface—it is sacrifice, risk, and transformation.

Moreover, in a time of increasing loneliness and disconnection, Aphrodite’s presence in myth offers a reminder of what it means to long for closeness. Her stories show us that even the divine can crave intimacy, that vulnerability is not weakness, and that to be drawn toward another is to feel the pull of something eternal.

Aphrodite’s Legacy

Aphrodite is more than the goddess of love—she is the force that drives creation, connection, and chaos. Her myths are not just about romance; they are about the essential human need to be seen, to be wanted, and to transcend the self through union with another. She represents both the joy and the danger of opening one’s heart.

In ancient Greece, Aphrodite shaped the moral and emotional imagination of a people. Today, she remains with us in art, in language, in the way we experience beauty and navigate desire. She is the ache behind a love song, the thrill of a first kiss, the pain of betrayal, the glow of admiration. She is in every heartbreak, every poem, every work of art that seeks to capture the ineffable power of love.

To study Aphrodite is to explore not only the myths of the past but the myths we live by now. She reminds us that love is not always pure, not always peaceful—but it is always powerful.

And it is that power that keeps her eternal.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

Discuss the nature of the reconciliation between Achilles and Agamemnon: Is it genuine forgiveness, a political necessity, or simply a response to grief and urgency?

In what ways does Achilles' refusal to eat symbolize his psychological and emotional state?

What is the significance of the horse’s prophecy to Achilles at the end of the book?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 20. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Olympian Gods in Arms and covers pages 503-520. In the Wilson translation, it is called The Warrior’s Return and covers pages 481-499.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I do wonder if this is a truce of desperation more than a reconciliation. It's just that defending the honor of his fallen friend is of greater importance than defending his own honor of being wronged.

I don't know how much carnage awaits us in the next book, but I can only imagine how much worse it would be if they were all hungry and sleep deprived. Way to go Odysseus.

(Also, it's probably just me, but every time Automedon is mentioned, I picture a transforming robot of some kind! It's just me, isn't it. 😂 Child of the 80's I guess.)

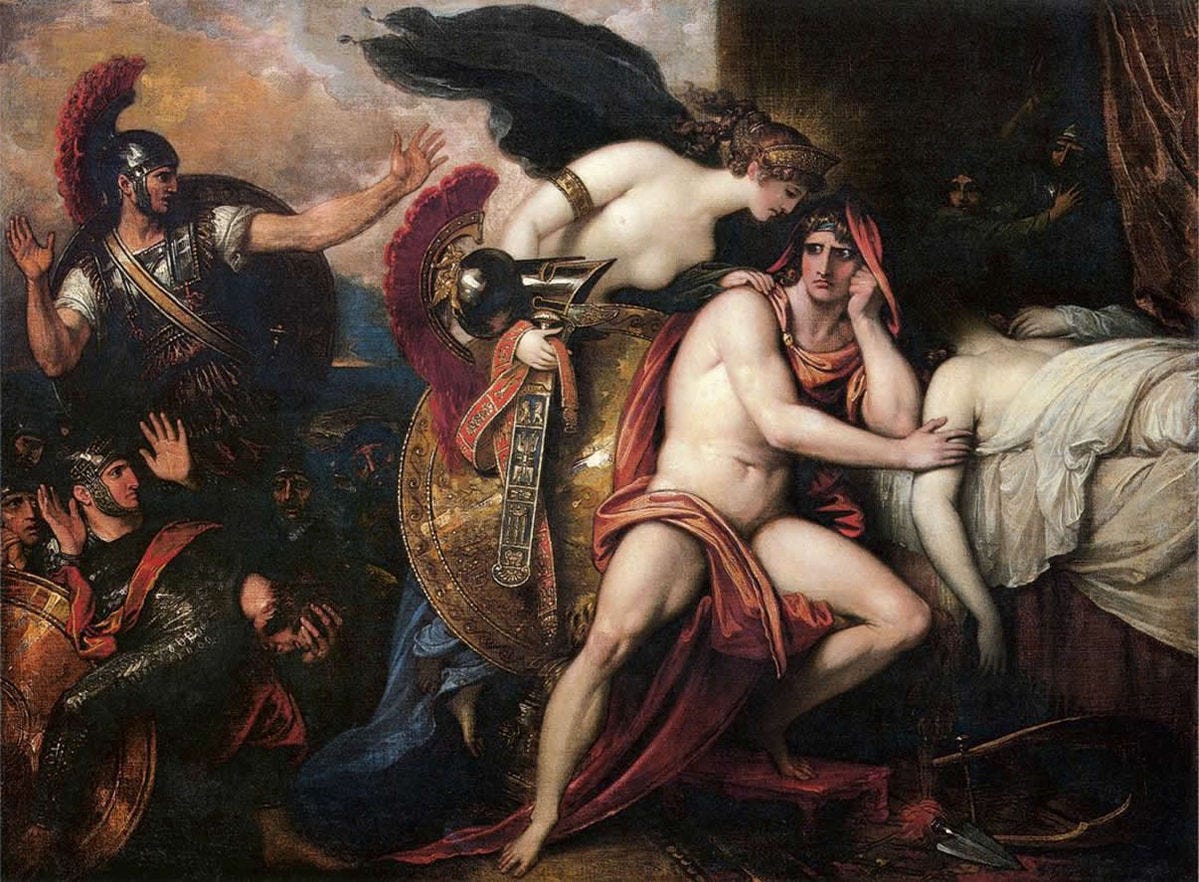

Love this. I hadn’t seen the painting, Briseis Given Back to Achilles by Peter Paul Rubens, 1630. The Horses depicted in the painting are incredible, and do look as if they can, and do, speak.