The Literary Obsessive - An Interview with Eleanor Anstruther

A Beyond the Bookshelf Profile

Exploring Life and Literature

Dear friends,

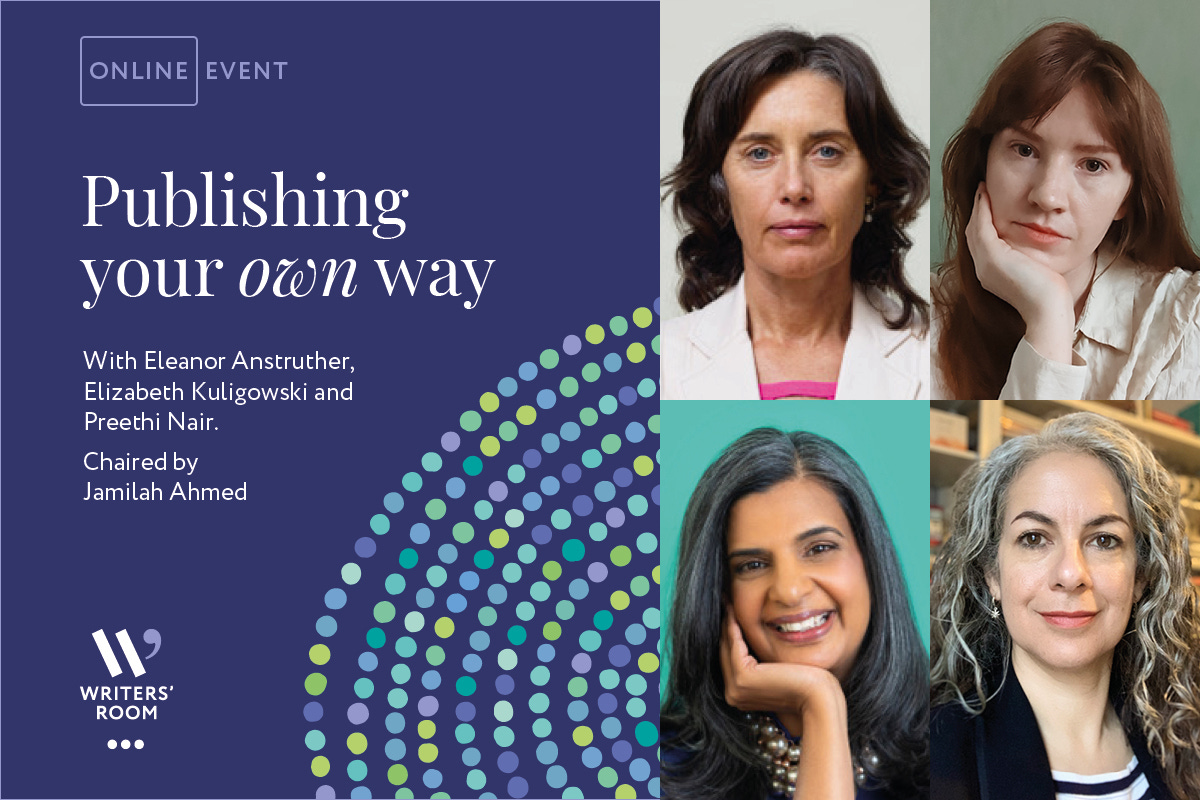

When planning my reading for 2025, I wanted to focus on women in literature during March, which happens to be Women’s History Month in the U.S. Last week, we focused on Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte, a book widely considered a classic of the novel form. This week, I felt it appropriate to move forward to the present with an introduction to an author I have come to know and love over the past year. Eleanor is not only a supremely talented writer, she is also an endlessly fascinating human. In today’s interview, we hear about her life as a reader and writer and her thoughts on women in literature. I hope you enjoy this exploration beyond the bookshelf as we continue our exploration of women in literature.

**This interview may be too long to read completely in your email and may need to be opened in your internet browser.**

grew up in London and West Sussex. While she currently makes her home somewhere between the two, her family’s story of how they came to England is quite the adventure. Her mother’s family was of Dutch heritage, and her father’s was Italian. Her father’s family traveled from Italy to fight for the Scottish King 1,000 years ago. They were rewarded with land in Fife, making the fishing village of Anstruther their home and taking its name for their own.Eleanor dropped out of Manchester University and ran away to India. From there, she traveled on and off for another decade, somewhere in the midst of which she started a commune and married her first husband. When that didn’t last, she went to Australia, where she met her second husband, a marriage which didn’t last either. Aged 37, she became a single mum of one-year-old twins living in a remote farmhouse, a tough gig she chose for herself, to which she added homeschooling until they were 11. Though challenging, she found this season of her life to be hugely fulfilling and reflects on it with great love and gratitude that she could do it. She considers herself a crazy cat lady with three currently in the house. In addition to the cats, she has a horse she adores. She says her life is a matter of rural life and writing.

Eleanor, thank you so much for being here. I would like to start with a few questions about reading. Would you share with us how reading came into your life?

I grew up in a house of books, in fact, as my parents didn’t live together, in multiple houses surrounded by books. I’ve never known life without them and what they contain; whole worlds, other minds, the joy of the magic that is literature. On top of that, I come from a long line of writers. My father before me, his aunt, uncle and great aunt, my cousin. We’re littered all over the place. I think I’m the first to go full pelt into literary fiction. The others were poets, biographers, essayists, that kind of thing.

How have your reading habits changed over the years?

Well there’s always school to put you off. Post being read to, but pre the liberation of adulthood, I dragged Shakespeare, Austen & Eliot about as if they were set to kill me, but the love never quite died and as soon as I was up and out of there, I picked up my love of books again, starting with the classics of the hippie trail such as On The Road, The Prophet, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, The Road Less Travelled, Illusions and The Teachings of Don Juan. From there I moved onto anything by Isabel Allende. During the commune years we all did The Artist’s Way. In hindsight, I guess that’s when my writing practice was reignited. I read every day now, I’ve always got a novel on the go. I pick carefully and keep learning.

Would you be willing to share a book that influenced you and how it did so?

As I’m reading it right now and it’s having a huge impact on me, I’d like to share Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright. It’s nothing short of magnificent. I can’t begin to do it justice by reviewing it; it’s as wild and funny and tragic as the crises it describes; there is Aboriginal sovereignty and the shadow of the Anthropocene. There is death and deep knowing. It’s utterly superb.

What are your thoughts on the importance of stories culturally?

We are stories. We are the literal embodiment of them. Our lives are made of them and telling them to each other is how we give context to relationship and how we relate. They are vital, as crucial as the air we breathe. I wish governments recognised that storytelling and the people who make it their contribution are as important as the other social services that we depend on, our hospitals and schools, our governing principles. Society grows thin without artists, communities suffer when their stories are stolen and people die when they lose track of the story of themselves. Like grass pushing through concrete, we will never stop telling the story of our lives to anyone who’ll listen. Stories are not just culturally significant, they are how we make sense of the world. The stories we tell inform where we’re heading, and owning your story is vital to your sense of self. Look at societies who’ve had theirs obliterated. Look at how much time and energy governments and big business put into owning theirs.

What genres do you prefer to read?

I’m against the term. It irritates me. As long as it’s good, I’ll read it. Having said that, it will have to be a long cold winter before I get around to Fantasy and Magical Realism.

What book do you think everyone should read in their lifetime and why?

Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah. Because it’s the truest form of literary spiritual wisdom I know. Or When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön.

Can you please tell us about an underappreciated novel that you love?

Angel by Elizabeth Taylor. The fact that I feel the need to say, Not the actress says it all about how relatively unknown she remains despite being one of our greats. Angel is the best of Taylor. It’s about a writer, and it doesn’t hold back. I’d also like to nominate Foster by Claire Keegan. Not that it hasn’t been appreciated, but relative to the hullabaloo surrounding Small Things Like These, not to mention the triple fandango given a certain fellow countrywoman, it is underappreciated. It’s a far cleverer, better, more pure piece of literature than any of the others put together. It’s a masterpiece.

How do you pick the next book you want to read?

Always a recommendation from a trusted source. I have a handful of friends in my life whose taste is stellar and standards high. If they tell me to read it, I read it.

Is there anything else you want to share with us about your reading life?

I read every day for about an hour. It’s the same practice as writing. Little and often, a sustained, repetitive schedule that moves mountains.

I started with questions about reading because that tends to be the foundation upon which a writing life is built. So, let’s transition into some questions about writing. How did you decide to start writing?

I’ve always written, and by that I mean I can’t remember a time I didn’t. My first book was written in a language all my own in a little pink notebook before I could read. At school, I took essay subjects, and when I set out on my travels, I kept a diary. My first attempt at a novel was written over a summer at the dying edge of the clinic I ran for a shaman (small “s” intended). He was away in Mexico and I put to paper the story of Lucy Jay who runs away to India. Almost entirely autobiographical and entirely terrible, it sits in a drawer as that first novel, the one you have to write in order to write the ones that aren’t so bad. It took me another decade before I really got down to serious work, a decade of insane stories written while high on crystal meth, casts of hundreds, impossible to read now for the picture they paint of my mind, but again, the urge was there. It was only when I got clean and got handed the story of my father’s sale by his mother to his aunt that my professional career took off.

What do you consider the most challenging part of the writing process?

All of it. Each part comes with its own headache. First drafts are special in that I’m pulling words out of the ether, communing with the unknown and creating something out of nothing. As Simone de Beauvoir says in She Came To Stay , "We seek to create the exact reproduction of something that doesn't exist." I’m very careful at first draft not to brow beat; I hold this part very lightly. It’s a matter of turning up every day at the same time and sitting quietly until the images, ideas, words come. The macro and micro edits use a different skill, and I can be tougher with the material. The draft after draft effort of it, oh boy, it’s exhausting, and material fatigue can kick in. But I always feel that the work that’s come to me deserves the best and I won’t rest until I’ve done my best by it, which means going over and over it, reading it aloud, running it past an editor, redrafting again. It’s laborious. And did I mention the horror that is the line edit?

Can you share with us what you have written and what you have in the works?

A Perfect Explanation (Salt), A Memoir in 65 Postcards & The Recovery Diaries (Troubador), In Judgement of Others (Troubador) are all out now and available through your favourite online retailer and in bookstores. They’re also available as eBooks and as audio books.

I was wondering if you would share with us a little about your writing process? What does your day look like when you are writing? Do you have a particular space you prefer to be in while writing?

Christmas and July excepted, I write every day starting at around 4:30 am and finishing by around 6:30. Once I’m at copy edit and proofread stage, I might start later and work mornings and afternoons depending on the rest of my schedule. Late stage editing takes a different part of my brain, one that doesn’t mind so much being interrupted, so I can risk the hours when the rest of the world is awake. I’m not precious about where I work, having a pram in the hall will teach you to be agile. I can work anywhere and often do. But for those early hours when the house is asleep I favour my stand up desk in what you used to be the schoolroom, now purloined by me as a workspace since Covid when I had to work and parent at the same time. My lovely old studio up in the garden I gave to one of my children (lucky them).

What risks have you taken with your writing that have paid off?

About 7 years and well over 20 drafts into my debut, my then agent dropped me. The novel, in an attempt to meet notes, had become a Frankenstein’s monster of someone else’s ideas; it was no wonder it wasn’t working. Having already lost what I felt was everything, I ripped it up and wrote from scratch the novella version of the story I’d been trying to tell all along. I took it to the York Festival of Writing where it got noticed, and 6 months later I signed with my current, wonderful agent Jenny at ANA. I’ve taken risks since, all borne of the same determination to get onto the page what I hear in my head and feel in my body, often against the taste and advice of the professionals around me. I’ve stuck to titles I like, tones felt to be too dark, stories felt to be too slim. If I don’t believe in it then ultimately no one will, and if I don’t hold fast to the truth I feel inside, then whatever I produce will not be me. This is not to say I don’t take notes, I do and often as every writer should. I put myself in the way of them all the time. What’s important is knowing which ones to listen to. Sometimes a good note is useful for how it determines which hill you’ll die on.

Who do you consider to be your literary influences?

Graham Greene, Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, William Thackery, Martin Amis, Joan Didion, Jane Austen, Jilly Cooper, all of the Brontë sisters, Stella Gibbons, John Fowles, Elizabeth Strout, Ann Tyler, Colm Tóibín, Edna O’Brian, Penelope Mortimer, Elizabeth Taylor – I’m sure you get the picture. I could fill pages with the names of the greats who’ve taught me to write as I’ve read.

What advice would you give to a writer working on their first book?

Finish the damn book. Get your first draft completed on the page before you start editing. Accept it takes a long time to get anything up to scratch and commit to not letting anything out the door until you’ve given it your best, which includes pausing between drafts, reading the work aloud and working with an editor.

Is there anything else about your writing life you would like to share with us?

I am obsessive – thus the title of my Substack, The Literary Obsessive. Pretty much everything in my life plays second fiddle to my writing life. It’s a magical, tough, brutal, wonderous and ultimately fulfilling way to live. I’ve learnt to keep my head down and my eyes on the page; everything good comes from focused work. There’s a temptation to go chasing the attributes of success, the events and reviews, the noise of it all but my advice is, don’t. Without a bubbling creative centre, the whole thing falls in on itself. Let the work produce results, and let those results be unexpected.

Thank you so much for that look inside your writing life. I think new writers must understand it isn’t all fun and games. A lot of work is involved, especially if you want to write well.

Let’s transition into some questions about women in literature. This month is Women’s History Month in the U.S. I want to highlight the contributions of women in literature. My first and best influence in writing was my grandmother, Juanita Yates, who, in addition to being a mother of 11 children, was a journalist and self-published author. She was indie before that became a thing.

Tell me, how do you view the evolution of women’s roles in literature throughout history?

Before I get into this I need to say that I’m writing from the peculiarly limited viewpoint of a white western education, the first female author I came across outside of that narrow band was Alice Walker when I was well into my twenties. But to answer the question based on the knowledge I have, do you mean as subjects? Objects? Or authors? It’s not that long ago that the term “authoress” was still in parlance (excuse me while I fetch my smelling salts), and as for being subjects, women were objectified in literature relentlessly, even by themselves until Mary Woolstencroft blew the lid off. As authors, women found their first footing in religious texts and poetry; I suppose those areas were felt less threatening to men and what men perceived to be the sensibilities of women, and their second in science and as essayists in social & political movements. The Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society draws a very good picture of where women had reached by the late 19th century. They’d punched a hole through the wall to tertiary education, but the emphasis was still broadly a matter of where they were allowed to go and by extension what they were able to say in public. The fact that there were riots at Cambridge when the ladies pushed to be awarded degrees for their studies says it all. But the major contributions to English literature of Shelley, Austen, the Brontës, Eliot, Alcott, Gaskell had moved the dial significantly enough that by the time the 20th century rolled around, bookshelves were set to receive the voices of the women who’d grown up with these books in their hands, to improve or revolt against, break the rules or deepen the art of storytelling. I grew up reading them, too, and for a long while in my thirties read only women, a counterbalance to what was still a male dominance on the shelves of The Classics. Our role has been to break out and break free, show the women and girls who read us how to use their voices, and through stories to tell them what’s possible. From Orlando to Rebecca, We Have Always Lived In The Castle to The Handmaid’s Tale, women have written shadow. State of the nation through kitchen drama has been our literary domain, a domain we were contained to in which tyrants and messiahs were born and brought up by us. At the stove we saw in fine detail how the world behaves unhooked from the public gaze. Woolf, De Maurier, Jackson and Attwood knew the secrets and were not afraid to say so. Thankfully the kitchen is to the most part a shared space now, but women’s observational skills at the minutiae of life, the small visible movements which imply the larger hidden intent, continues to inform our work wherever it’s set. I consider the shadow skills to be implicit in my role as an author.

Are there any specific female authors or literary movements that have significantly influenced your perspective or work?

I was very influenced by Woolf when I set out, and by extension the whole Bloomsbury set. Theirs was a movement of equality, a shared fascination with the possibilities of where art could take them in all its forms. Charleston exemplifies their collective life with its painted walls, I particularly loved the bedroom of Maynard Keynes with its block red and black. They were sexually, romantically and critically free. Their love of experimentation reached every corner of their lives. Garsington Manner, Monks House, Sissinghurst, these have all been places of pilgrimage for me. There’s also a family connection which informs my sense of familiarity; my great aunt Joan and her lover Pat were in the set.

What challenges do you think women authors have faced historically, and do you feel those challenges persist today?

Where do I start?! Being heard. Being seen. Being taken seriously. Our cross gender battle to dismantle the pyramid scheme of hierarchy in selling. There is room at the top. Can I say that any more clearly? The notion that there can be only one Strout or Tyler or Enright is nonsense and I wish marketing departments would recognise this. Each of those titans of literature are irreplaceable and unique, but that doesn’t mean there can’t be a multitude more if you’re good enough. I sat next to a screenwriter years back when Fleabag was hitting its bullseye, and she told me a TV exec had said, but we already have a Phoebe Waller Bridge as if we are interchangeable. Heavens above. And here’s another fury: the very idea of something called “Women’s Fiction”. I know that the fiction market is largely held up by female readers, that women read more fiction than men – the why is too big a subject to get into here, but must we gender the content? What’s the point? It’s reductive and baseless and totally unhelpful. It only strengthens the idea that reading is for girls when we all know that reading is for human development, joy, and solace. It teaches us how to connect with ourselves and each other, it informs who we are and explores relationship of every stripe from romantic to sexual, spiritual to political. Reading stories is essential to growth. It has as much to do with gender as a tree or a cat or the stars. Who wrote a book, in terms of which gender, is irrelevant. What matters is content.

Can you share a book by a female author that had a profound impact on you and why?

I wrote my A ‘level thesis on A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Woolstencroft. I think it was my first literary taste of feminism. I grew up in a strong female household, my mother and various cousins teaching by example that I could design my life how I wanted it to be. It never occurred to me to be constrained by the cliches of my gender. Woolstencroft’s dismantling of the straits in which she lived was music to my ears and gave me grounds to understand my present. Discovering Woolf and Orlando had a huge technical impact on me. Likewise Jane Eyre, The Wide Sargasso Sea, and We Have Always Lived In The Castle taught me shadow and darkness, while Cold Comfort Farm taught me funny.

Are there any contemporary female writers whose work you find particularly inspiring or groundbreaking?

Claire Keegan, Alexis Wright, Hanne Ørstavik. They’re all masters. Likewise Elizabeth Strout, Ann Tyler, Miranda July, Hilary Mantel and Anne Enright.

How would you describe the state of representation and recognition of women in literature today?

The Women’s Prize Trust is doing immense work on behalf of women’s representation and recognition in the wider world of modern literature. In terms of global reputation, I think it’s safe to say we’ve proved our point. The snare that still trips me up is the gendering in genre and by extension, bookshops; any phrase which describes a work according to the sex of its author. The Women’s Prize describes authors by gender, but not what they write about or who reads them. This distinction is crucial. I’d like to see an end to the gendering of content and a recovery from the patriarchal damage that reading fiction is a female pastime.

Do you believe the publishing industry has become more inclusive of women’s voices, and if not, what changes would you like to see?

There’s an argument to say that the publishing industry is largely run by women, and I’ve heard complaints from male authors that the bias by middle aged, middle class educated white female editors is skewing the industry and not in their favour. Having said that, the patriarchy infects everyone with its own special bias, and those self-same female editors might, in the same breath, list in the top ten serious works of literature those mostly by men, while ask them to list the top ten influential works and you’ll see more women pop up. This idea that men write the world and women write the kitchen, that men make their point through heavy hitting statements, and women by domestic device isn’t far off the mark, but it’s the word serious which gets me, a persistence in the fallacy that dissecting from the inside out, the small to the big is less serious than coming at it from the outside; Bellow as opposed to Attwood. I’d like this attitude unravelled and to be seen for what it is, a bias that says women are fascinating but leave the important stuff to men. This maybe my childhood showing, but a woman in charge politically still clearly frightens the shit out of most people, and as a barometer to sexual equality it leads that novels by women are still perceived as playing with ideas rather than being ideas.

Why is reading such an integral part of your life, and how does it influence your writing?

A writer has to read. It’s absolutely integral to growth. I have learnt everything from the authors with which I’ve surrounded myself. They’ve taught me what’s possible and how to do it. It’s also a balm for my soul, a deep pleasure, an immersion which soothes and makes me happy.

How do you approach writing? Can you describe your writing routine or habits?

With trepidation! Fear and doubt, a sinking feeling, terrible nerves. All of these feelings accompany me as I turn up each morning for work. It never feels short of a miracle that the work turns up to greet me, that after an hour or two there’s something on the page. It is the greatest joy and the deepest terror. I love it. I’m very disciplined, routine is key. I’m currently on a first draft of a new novel, and at this stage it’s a matter of rising at about 4am, taking a cup of mushroom coffee to my desk and waiting quietly as if on safari, ready to raise my binoculars. I sit still and I listen and amazingly the words and images and characters creep out of hiding. There’ll always be a moment when a voice in my head says, That’s enough. Stop there. Which obediently, I do. I’ve learnt never to force it at first draft. It’s so delicate, any personal beating will break it. It’s not my job to understand what’s appearing on the page at this early creation stage, I’m simply there to translate it. Making sense of it will happen later.

What do you hope readers take away from your work?

A sense of self. I endeavour to write the human experience, to leave the page and talk to you directly, to swim up from the depths of human consciousness and bring with me things for you to see through the medium of story. I hope too that readers are left with the feeling that they’ve had a good time. The experience has got to be enjoyable, whatever the book’s about.

If you could give one piece of advice to aspiring female authors, what would it be?

Forget the female part and write from the human, this shared experience told through the lens of your lived experience. There is nothing you cannot say, so say it. Forget what others might think. Your voice is unique. Be bold and be you and tell the story you need to tell. Every single one of us who does this lays the path for those who come next, creates a blueprint for women of the future and strengthens the message of humanity. Also, whatever your route to publishing, standards, please. Keep them high.

How do you see your work contributing to the broader conversation about women’s roles in literature and society?

I’m an anarchist and a feminist and I write books of protest as much as the kitchen dramas of my forebears. In taking my own advice, my books are a shout from the heart and contribution to this thing called humanity that authentic voice inspires others to do the same. I have never taken no for an answer, and in that my path to publication has been mainstream and indie, the latter route to great extent I’ve had to pave myself. The novels which the mainstream didn’t want have all been women centric in terms of plot and character, and perhaps the women in them haven’t suited an idea of how women should be, or perhaps my deep dive under the hood of women has been not to the mainstream editor’s taste, but their reception here on Substack has proved they are wanted and needed and celebrated, so my route to publishing them as an indie artist is as much about the broader conversation about women’s roles as it is about the state of the publishing industry today.

Do you have any upcoming projects or books that you’re particularly excited about and would like to share with readers?

My latest novel, In Judgement of Others, came out in January. I hope you’re all excited to read it. It explores psychosis by way of three female characters in a British home counties setting. It’s dark and funny and I’m hugely proud of it. Please tell your friends.

Are there any hidden gems by female authors you’d recommend to your readers?

For comedy Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons is a classic. For perfection, Angel by Elizabeth Taylor.

Where can people connect with you online?

On Substack they can find me at The Literary Obsessive or through the contact form on my website eleanoranstruther.com . If social media’s your jam, I’m in the usual places, Insta, Bluesky & LinkedIn are the ones I check most often but there’s always the bizarre X or slightly dull Threads….

Eleanor is authentic in her writing and her life. Please check out her publication The Literary Obsessive at the link below.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Excellent interview. And very encouraging to both men and women writers in lots of ways. Especially appreciate the tilt towards individual independence tempered by the struggle to finally write something worth reading. Also the discussion of how harmful the gendering of life, writing and the desired perspective of those who would succeed must be. In regards to male versus female writing, if the concerns of the kitchen aren't given adequate attention then the whole house and everything outside will shred into tatters. If we have so far survived having World War III it will be partially because of the sensibility of writers like Virginia Woolf. A better or even recognizable masculine sensibility is often sabotaged by testosteronic inflexibility seen in the writing of Philip Roth as compared to that of Woolf. There is a stultifying emotion block stimulated by the severe objectification of women one sees in Roth as early as in "Goodbye Columbus." Don't want to go bonkers over all this but this interview is a great discussion, a great conversation. Thanks for this great Substack.

This is such an interesting interview, Matthew, and Eleanor is a wonderful subject (so well read, & her comment on fantasy fiction did make me laugh). I will be saving this to re-read in the coming weeks, and very honoured that Cambridge Ladies' Dining Society gets a mention.