Exploring Life and Literature

Dear friends,

In a world brimming with prose, poetry stands as a beacon of distilled human experience—a genre that captures the ineffable with a few deft strokes of language. April, recognized as National Poetry Month, offers an opportunity to celebrate this timeless literary form. To honor poetry is to acknowledge its role as both a reflection of and a force within culture. From its ancient origins to its contemporary manifestations, poetry has given voice to beauty, sorrow, rebellion, and hope. It has shaped civilizations, influenced politics, and preserved the human spirit. As we celebrate National Poetry Month, we honor not only the craft of language but also the courage of expression. Poetry’s power lies in its ability to articulate what often feels beyond words—the unspeakable sorrows, the fleeting joys, the quiet moments of revelation. It reminds us that language, at its most artful, can be transformative. In the verses of the ancients, the romantic cadences of the 19th century, and the raw immediacy of contemporary spoken word, poetry remains a vital creative force.

Poetry’s origins stretch back to humanity’s earliest artistic expressions. In pre-literate societies, it was a form of oral storytelling, passed down from generation to generation. Rhythmic structures, repetition, and mnemonic devices made it easier to memorize and preserve. The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BCE), one of the oldest known literary works, offers a glimpse into this ancient form, blending myth, heroism, and existential reflection.

In ancient Greece, poetry became more formalized with works such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey—epics that not only entertained but also preserved history and cultural identity. The Greeks also developed lyric poetry, a more personal and emotive form, exemplified by Sappho’s passionate fragments of love and longing.

Throughout the Middle Ages, poetry remained a dominant form of expression, whether in the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf or the elegant courtly verse of the troubadours. The development of written language enabled poetry to become more fixed and transmissible, though it remained largely oral in performance.

The Renaissance marked a flourishing of poetic creativity in English literature. The works of Geoffrey Chaucer, notably The Canterbury Tales, brought a rich narrative quality to verse. William Shakespeare elevated poetry with his sonnets, crafting 14-line meditations on love, beauty, and mortality. During the 17th century, metaphysical poets like John Donne and Andrew Marvell infused poetry with philosophical complexity and startling metaphors, while John Milton’s Paradise Lost presented a grand, tragic epic in blank verse.

By the Romantic era, poetry became a vehicle for individualism and emotional expression. William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and John Keats captured the sublime beauty of nature and the depths of human feeling, often in response to the Industrial Revolution’s dehumanizing effects.

The Victorian period saw poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Matthew Arnold grappling with the tensions of faith, progress, and the human condition. At the century's end, the decadent and symbolist movements, led by figures such as Oscar Wilde and W.B. Yeats, experimented with poetic form and aesthetics.

The 20th century brought seismic shifts in poetic style and subject matter. Modernist poets such as T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and William Carlos Williams broke with traditional forms, embracing fragmentation, allusion, and free verse. The postwar period saw the emergence of Confessional poetry, with writers like Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Robert Lowell offering raw, intimate explorations of mental illness, love, and despair. Simultaneously, the Beat poets, including Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, rebelled against conformity, infusing their work with jazz rhythms and countercultural themes.

In the contemporary era, poetry continues to evolve. Spoken word and slam poetry bring the form back to its oral roots, while poets like Ocean Vuong, Tracy K. Smith, and Claudia Rankine use poetry to address race, gender, and the immigrant experience with powerful immediacy.

Poetry has always been more than mere aesthetic expression—it is a cultural force. Across centuries, it has been wielded as a form of protest, resistance, and social commentary. During the Harlem Renaissance, poets like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay gave voice to the Black experience in America, capturing both joy and injustice. In Chile, Pablo Neruda’s verses blended love and revolutionary fervor. In the United States, Maya Angelou’s poetry became a voice of civil rights and empowerment, while Adrienne Rich’s feminist poetry dismantled patriarchal norms.

Poetry also serves as a bridge between the personal and the universal. It gives language to individual grief, love, and wonder, yet resonates with shared human experiences. It distills complex emotions into a few lines, making the abstract tangible. Through metaphor, rhythm, and form, it transcends the ordinary, allowing us to see the world anew.

While poetry spans cultures and languages, certain poets in the English tradition have left indelible marks:

William Shakespeare (1564–1616): His sonnets, with their lyrical beauty and existential musings, remain foundational to English literature.

John Milton (1608–1674): His Paradise Lost exemplifies the power of epic poetry to explore theological and human struggles.

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886): With her compact, enigmatic verses, she captured the complexities of existence, love, and death with haunting precision.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892): His free verse in Leaves of Grass celebrated democracy, individualism, and the human spirit.

T.S. Eliot (1888–1965): The Waste Land redefined modernist poetry with its fragmentation, literary allusions, and despairing vision of postwar disillusionment.

Sylvia Plath (1932–1963): Her confessional poetry in Ariel explores identity, suffering, and alienation with searing honesty.

Seamus Heaney (1939–2013): His poetry, rooted in Irish rural life, explores themes of memory, conflict, and the power of language itself.

This year, in preparation for National Poetry Month, I chose to read a collection of poems by Mary Oliver. While I had heard much about her, especially as I am keenly interested in nature and the natural world, I had never read any of her work. I discovered that she is a beacon of clarity and grace. Her work, infused with awe, simplicity, and reverence for the natural world, captures the transcendent beauty found in ordinary moments. With a voice both tender and assured, Oliver invites readers to slow down and notice—to dwell in the presence of a bird’s song, the curve of a river, or the fleeting touch of human love.

Born in 1935 in Maple Heights, Ohio, Mary Oliver grew up finding solace in nature. She wandered through woods and fields, observing and absorbing the quiet marvels of the natural world. These early experiences shaped her poetic sensibility. Inspired by Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau, Oliver’s poetry exudes a spirit of contemplation and reverence, infused with a near-spiritual connection to the earth.

Her work, however, is not purely pastoral. It also carries profound existential weight, exploring grief, solitude, and the human condition. With collections such as American Primitive (which earned her the Pulitzer Prize in 1984) and New and Selected Poems (which won the National Book Award in 1992), Oliver established herself as a poet of both accessibility and depth. Her plainspoken language belied the complexity of her themes—mortality, spiritual longing, and the search for grace in a fractured world.

Oliver’s poems often feel like prayers or meditations—deceptively simple in form yet brimming with wisdom. She celebrated the everyday with reverence: the flight of geese, the arc of a wave, the brief flicker of sunlight on water. Her enduring question, as expressed in her beloved poem “The Summer Day,” echoes through much of her work: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

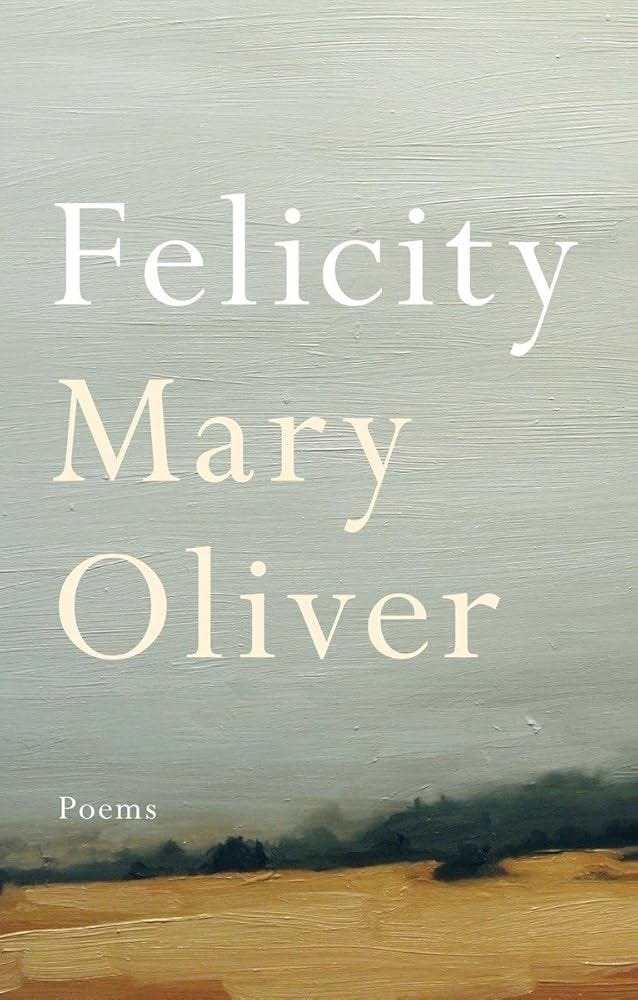

Published in 2015, Felicity arrived as a poignant late-career offering from Oliver, revealing her gentlest and most radiant voice. While much of her previous work centered on nature, Felicity turns inward, exploring the nature of love—romantic, spiritual, and self-reflective. The collection is divided into three sections:

"The Journey", which contemplates longing, connection, and the restless pursuit of meaning.

"Love", the core of the collection, offering delicate yet profound reflections on human affection.

"Felicity", a closing section that embodies a sense of quiet acceptance and joy.

Throughout the collection, Oliver’s signature style prevails: short, elegant lines, unadorned diction, and moments of quiet revelation. Her minimalism gives the poems an ethereal quality, allowing space for the reader to linger and reflect.

At the heart of Felicity is a celebration of love in its many forms. Yet Oliver’s portrayal of love is neither saccharine nor idealized. It is, instead, deeply human—marked by vulnerability and fleeting grace.

In the poem "Moments", Oliver captures the urgency of love—the way it compels us toward selflessness and risk. Her language is spare, yet the emotional resonance is profound:

“There are moments that cry out to be fulfilled.

Like, telling someone you love them.

Or giving your money away, all of it.”

The collection is also replete with meditations on transience and simplicity which are quintessential Oliver—a gentle nudge toward reverence for the everyday sacred. In "I Wake Close to Morning", she writes:

“Why do people keep asking to see God’s identity papers

when the darkness opening into morning

is more than enough?”

Felicity is a radiant collection—a tender benediction for those who have loved deeply, lost profoundly, and still marvel at the small miracles of the everyday. Its title, derived from the Latin word for happiness, reflects its essence: a celebration of life’s fleeting but exquisite joys.

What makes this collection so remarkable is its simplicity. Oliver’s poems, often brief and unembellished, contain multitudes. They are windows into a contemplative soul, offering glimpses of wonder, gratitude, and hard-won wisdom. The spareness of her language belies its richness. In a mere handful of lines, she evokes a lifetime of feeling.

Felicity is also remarkable for its intimacy. While Oliver’s earlier works often focus on solitary communion with nature, this collection draws closer to the human heart. It is about vulnerability and connection—the beauty of opening oneself to another and the quiet contentment that follows.

As a preparation for National Poetry Month, reading Felicity was an inspired choice. It embodies the enduring power of poetry to magnify the seemingly small moments of existence—reminding us that a sunrise, a passing breeze, or the tender hand of a loved one are miracles worth celebrating. In the tradition of great lyric poets, Mary Oliver reminds us that poetry’s greatest task is not to dazzle with complexity but to illuminate with simplicity.

In Felicity, Oliver accomplishes this with breathtaking elegance, leaving behind a collection that lingers in the heart—a testament to her belief that even in our brief, imperfect lives, there is joy enough.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see how you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

This is such a lovely piece. I love this passage: "Poetry’s power lies in its ability to articulate what often feels beyond words—the unspeakable sorrows, the fleeting joys, the quiet moments of revelation. It reminds us that language, at its most artful, can be transformative." So well said!

Thank you for this heartfelt intro to Mary. I have one of her books but haven't cracked it open more than once. I thought (perhaps wrongly) that it was too religious. But maybe it's spiritual? I've been enjoying Ursula Le Guins final collection of poems called So Far So Good, edited and published after her death.