The Shield of Achilles

The Iliad Book 18

Exploring Life and Literature.

“A black cloud of grief came sweeping over Achilles. Both hands clawing the ground for soot and filth, he poured it over his head, fouled his handsome face and black ashes settled onto his fresh clean war-shirt. Overpowered in all his power, sprawled in the dust, Achilles lay there, fallen...”

Dear friends,

Book 18 of The Iliad marks a pivotal emotional and thematic shift in Homer’s epic. Following the death of Patroclus in Book 16 and the brutal battle for his body in Book 17, this book returns the focus to Achilles—arguably the central figure of the poem—and begins his transformation from rageful recluse to avenger, mourning friend, and ultimately, the instrument of fate. The narrative is somber, yet it crescendos into one of the most beautiful and symbolically rich passages in all of Western literature: the forging of Achilles’ new armor by the god Hephaestus.

The book opens with Antilochus delivering the devastating news of Patroclus’ death to Achilles. Achilles, who had previously withdrawn from the war out of pride and anger over Agamemnon’s insult, is now struck by a grief that transcends rage. His reaction is immediate and visceral: he collapses, covers himself with dust, and tears at his hair. It is a portrait of primal mourning, and Homer spares no detail in conveying the depth of Achilles’ loss. This is no longer the wrath of a wounded ego; this is the agony of a man who has lost the closest person to his heart.

His mother, Thetis, the sea goddess, hears his cries from the depths of the ocean and comes to comfort him. Achilles tells her he must now return to battle, fully aware that this choice seals his fate. He will die young, but he will die avenging Patroclus. Thetis, devastated by the knowledge that she will soon lose her son, agrees to help him and promises to return with new armor, knowing he cannot face Hector without it.

Meanwhile, on the battlefield, the Achaeans remain at the defensive, struggling to carry Patroclus’ body back to their ships. The Trojans press forward under Hector’s lead. The tension builds until Hera intervenes, sending the god Iris to Achilles with a message: he must show himself at the trench to rally the Greeks, even if he does not yet enter the fight.

Achilles heeds the call. Standing at the trench, he gives a mighty war cry, and Athena crowns his head with a golden fire. His voice alone, amplified by the gods, terrifies the Trojans and halts their advance. It is a moment not of combat, but of symbolic power. The very presence of Achilles reshapes the battlefield.

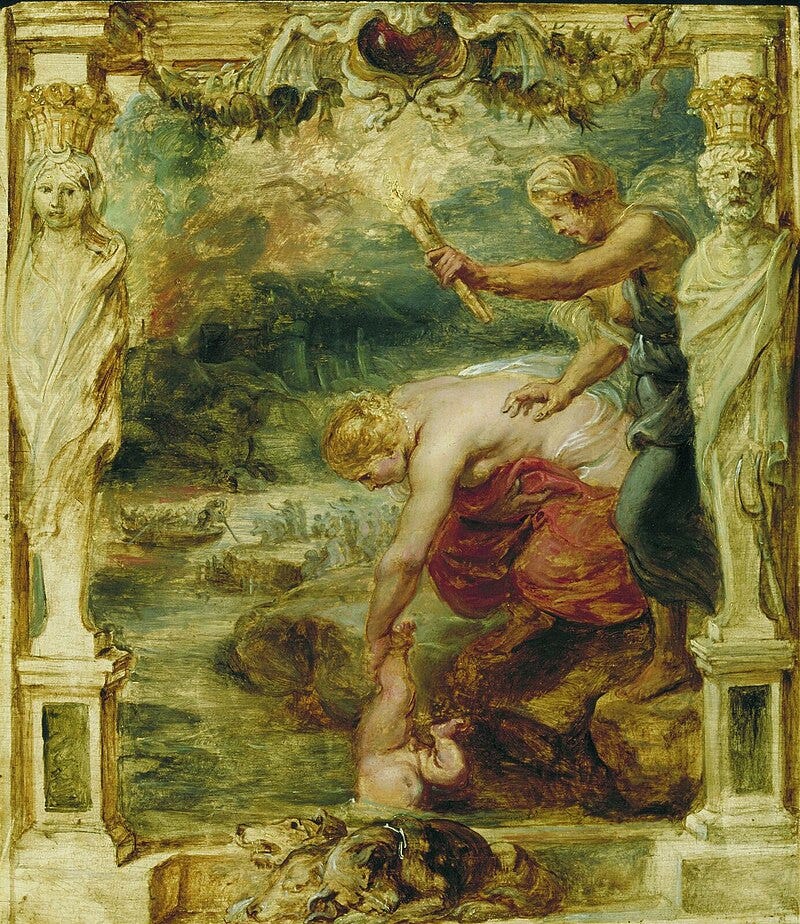

The final and most iconic section of Book 18 takes place in the forge of Hephaestus. At Thetis’ request, the divine smith begins to craft new armor for Achilles, including a spectacular shield. This shield is not just a piece of armor—it is a microcosm of the world itself. Homer describes it in a rich ekphrasis, detailing five concentric scenes: a city at peace, a city at war, a field being plowed, a vineyard being harvested, and a scene of pastoral life. Stars and celestial bodies frame the whole.

This shield is no ordinary object; it is the cosmos in miniature, encompassing human life, toil, joy, struggle, and cosmic order. When the book ends, the armor is nearly complete, and Achilles stands poised to re-enter the war, no longer only the wrathful hero, but something more complex and deeply human.

Book 18 is a masterpiece of emotional and philosophical depth, marking Achilles’ reawakening not just as a warrior, but as a human being facing the inevitability of death. The themes of grief, fate, sacrifice, and the human condition resound with stunning clarity. As Achilles mourns Patroclus, the poem moves from external conflict to internal reckoning.

Achilles’ grief in this book is perhaps the most raw and honest emotional display in the entire Iliad. Homer strips away Achilles’ pride, glory, and even his physical strength to reveal the aching vulnerability beneath. The loss of Patroclus is more than a turning point in the war; it is a turning point in Achilles' soul. His rage, which has defined the first half of the epic, becomes redirected—not toward Agamemnon or the Greeks, but toward mortality itself. He no longer seeks glory to spite others; he seeks it to honor the dead and fulfill his destiny.

The presence of Thetis in this moment of despair is also striking. Their interaction offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the mother-son relationship in the ancient world. Thetis cannot save her son, but she can offer comfort and assistance. Their dialogue is deeply human, touching on love, powerlessness, and the knowledge that to be divine is not to be immune to sorrow. It is a theme mirrored in today’s world: parents grieve for their children, not because they lack love, but because even love cannot shield us from loss.

The crafting of the shield of Achilles stands as one of the most famous ekphrastic passages in all of literature. It is not merely decorative—it is deeply symbolic. By embedding scenes of daily life, peace, and war into the shield, Homer presents a vision of life in its full complexity. This scene transforms Achilles from a figure of rage to a man who carries the world—its joy and its suffering—into battle. In essence, he becomes the vessel of all human experience. The shield is a mirror of life’s totality, suggesting that while we fight, love, grieve, and toil, the cycle of life continues.

Modern readers may find deep resonance in this transformation. Achilles’ grief and decision to return to battle out of love and loyalty remind us that heroism is not found only in strength, but in devotion. The recognition of life’s fragility and the choice to live meaningfully despite it speaks to the existential questions we face today: What do we do with our time? How do we honor those we’ve lost? How do we carry the weight of the world on our shoulders?

The shield itself has modern analogues. Consider memorials such as Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial or the 9/11 Museum in New York—these are symbolic constructions that seek to capture the scope of human experience in times of crisis and loss. Like Achilles’ shield, they do not merely record history—they embody the emotional and philosophical struggle to make sense of it.

Achilles’ appearance at the trench, even before he fights, is also significant. His presence alone inspires the Achaeans and frightens the Trojans. It is a reminder of the psychological dimension of leadership—how symbols, voices, and images can influence the course of events. In modern contexts, this is akin to the influence of public figures, speeches, and moments of unity that rally people in times of division or despair. Achilles at the trench is the image of potential realized, of identity reclaimed, of purpose reborn.

Perhaps the most profound modern relevance lies in Achilles’ acceptance of fate. He knows he will die if he returns to battle, but he chooses to go anyway. This is not a resignation to fate, but a courageous embrace of mortality. In an age often defined by denial of death—through cosmetic culture, technological distraction, or the pursuit of legacy—Achilles reminds us that the confrontation with death can clarify who we are and what we value.

He fights not just for Patroclus, but for what Patroclus represents: loyalty, friendship, shared purpose. These are ideals that transcend time and culture. Achilles becomes a tragic hero not because he dies, but because he chooses to live with full awareness of that death. This is what makes him timeless.

The Return of the Hero

Book 18 is the Iliad’s emotional and philosophical fulcrum. It transforms Achilles from an emblem of wrath into a fully realized human being. His grief, his love for Patroclus, his decision to face death, and the forging of his armor—all these mark a profound evolution of character.

In its exploration of mourning, fate, symbolic representation, and human purpose, Book 18 resonates across millennia. It reminds us that suffering is not the opposite of heroism but part of its essence; that to love deeply is to grieve deeply; and that to accept mortality is to embrace the full measure of life.

The shield of Achilles, with its concentric images of peace, war, harvest, dance, and stars, remains one of the greatest metaphors in literature. It reflects us all. We are warriors and lovers, builders and destroyers, farmers and dancers, children and mourners. We live, we die, and we pass on the shield.

In a world where so much feels uncertain and fractured, Book 18 offers not answers, but clarity: in grief, purpose; in mortality, meaning; in love, enduring strength.

“But when Achilles rose and showed himself to the Trojans, a rising flame flaring from his head, Athena’s gift— the goddess swept a golden cloud from his shoulders, a fire blazing in all its glory.”

The Man Beyond the Myth

Achilles is one of the most enduring and enigmatic figures in Western mythology. Though often remembered for his unmatched martial prowess, divine lineage, and tragic death, his story is far more complex than that of a mere warrior. He is not only a central figure in Homer’s Iliad but also a symbol of the human struggle with mortality, rage, grief, and meaning. To understand Achilles is to explore not only ancient Greek ideals of heroism but also the timeless emotional dilemmas that define us all.

His myth straddles the border between history and legend, and though there is no conclusive archaeological evidence that Achilles was a real person, his image has persisted for over two millennia as the archetype of the flawed hero. To trace the arc of Achilles’ life—through literature, historical context, and character analysis—is to explore the very soul of epic storytelling and the tragic cost of greatness.

The Historical and Mythological Identity of Achilles

Achilles is the son of Peleus, a mortal king of Phthia, and Thetis, a sea nymph or minor goddess. This union between divine and human sets the stage for Achilles’ life: one foot in the mortal world, the other in the realm of gods. According to myth, Thetis tried to make her son immortal by dipping him in the River Styx, but she held him by the heel, leaving that part vulnerable—a detail that gave rise to the modern term “Achilles’ heel.”

While there is no evidence to prove Achilles lived, he likely represents a cultural memory of a real warrior-chieftain or a composite of several heroic figures from the Mycenaean period (approximately 1600–1100 BCE). His world, as depicted in The Iliad, reflects a society of warrior-kings and aristocratic values—where fame (kleos) and honor (timē) are the cornerstones of identity.

Homer’s epics were written down around the 8th century BCE, long after the supposed events of the Trojan War. They likely draw upon oral traditions that preserved the memory of past conflicts and heroic deeds. In this light, Achilles becomes both a historical echo and a moral fable—more than a man, less than a god, and never entirely at peace in either role.

Achilles in Literature: Homer and the Epic Legacy

Achilles dominates The Iliad, though he is curiously absent from much of the action. The epic does not recount his early life or even the famous slaying of Hector until late in the narrative. Instead, Homer chooses to focus on Achilles’ wrath—his mēnis—which sets the entire epic in motion. Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek coalition, insults Achilles by taking his war prize, Briseis. Achilles, feeling dishonored, withdraws from battle, and the Achaeans suffer as a result.

What makes Achilles a compelling figure is not simply his might in battle but his inner turmoil. He is a man aware of his destiny: if he fights, he will die young but live forever in fame; if he refrains, he will live a long, obscure life. His choice to return to war after the death of his beloved companion Patroclus marks a profound turning point in the narrative. Achilles’ grief transforms him. His rage becomes not about wounded pride but about loss, justice, and the inevitability of death.

In the Odyssey, Achilles appears in the underworld, and Odysseus greets him as the most blessed of the dead. Achilles replies: “I would rather be a paid servant in a poor man’s house and be above ground than king of kings among the dead.” This moment starkly reveals Achilles’ evolving understanding of life and glory. It is one of Homer’s most poignant philosophical gestures—suggesting that even the greatest hero would trade immortality in song for a single breath of ordinary life.

Later authors expanded upon Achilles’ myth. In Statius’ Achilleid, we learn of his early life disguised as a girl on the island of Scyros to avoid the war. In Euripides’ Andromache and other Greek tragedies, we see the far-reaching consequences of his actions. Even Roman authors such as Virgil, though critical of Greek heroes, pay homage to Achilles’ martial legend through Aeneas’ encounters with his son, Neoptolemus.

Achilles as a Hero: Complexities of Strength and Suffering

Achilles challenges the simplistic definition of a hero. Yes, he is the strongest warrior, blessed by the gods, nearly invincible in battle. But his strength is always paired with vulnerability—not just physical (his heel), but emotional, psychological, and moral. His wrath isolates him. His grief breaks him. His love for Patroclus drives him beyond reason.

What makes Achilles truly heroic is his capacity to grow. At the beginning of The Iliad, he is proud, aloof, and self-interested. But by the end, especially in Book 24, when he returns Hector’s body to King Priam, Achilles shows empathy, humility, and even a form of grace. The image of Achilles and Priam weeping together—one for his dead son, the other for his lost friend—is one of the most human scenes in all of literature. It reminds us that even warriors must reckon with sorrow.

Achilles embodies the concept of kleos aphthiton—imperishable glory. Yet Homer questions whether such glory is worth the suffering it demands. Achilles’ greatness is inseparable from his doom, and his story asks whether we are defined by our achievements or by our capacity for love and loss.

Achilles in the Modern Imagination

Why does Achilles still matter today? His story continues to resonate because it reflects the universal tension between ambition and emotion, rage and reflection, mortality and legacy. He is not a hero because he is perfect, but because he feels deeply. His journey mirrors our own struggles with identity, loss, and purpose.

In modern times, Achilles often appears as a symbol of the gifted but tormented individual. He has been reinterpreted in novels, films, and scholarship as everything from a queer icon to a psychological case study. In Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, for instance, the love between Achilles and Patroclus takes center stage, emphasizing emotional intimacy over martial valor.

In cinema, films like Troy (2004) cast Achilles as a brooding anti-hero—charismatic but flawed, proud but introspective. These adaptations capture a truth that Homer knew: Achilles is not only a demigod of war, but also a mirror for human contradiction.

In the military, sports, and the arts, the figure of Achilles lives on as a symbol of exceptional talent, cursed by vulnerability. His “heel” has become a shorthand for fatal flaws, and his narrative continues to challenge the notion that strength and sensitivity are mutually exclusive.

Achilles and the Human Condition

At its core, the myth of Achilles is about what it means to be human. He is torn between two paths: to live long without glory, or to die young and be remembered. This is not just a mythic dilemma—it reflects our own questions about risk, reward, legacy, and meaning.

His grief over Patroclus is perhaps the most powerful emotional event in The Iliad. It is not glory, but love, that drives Achilles back into the war. He realizes that the cost of caring is vulnerability, and yet he chooses to feel deeply anyway. This capacity for transformation through love and loss makes Achilles enduringly relatable.

Modern readers, living in a world increasingly defined by moral complexity and emotional disconnection, may find in Achilles a kind of emotional honesty. He does not hide his tears, his fears, or his rage. He does not conform to stoic ideals of masculinity. Instead, he embodies the reality that to be strong does not mean to be numb.

The Flame That Burns Bright

Achilles is not simply a figure from a long-lost age of bronze and blood. He is a symbol of the enduring human desire to matter, to love, to rage, and to grieve. His greatness lies not just in his martial prowess, but in his emotional depth and moral reckoning.

He reminds us that heroism is not about perfection. It is about passion, loss, and the choice to act despite knowing the cost. He stands at the edge of life and death, and his choice to fight on, to burn brightly and briefly, is both tragic and sublime.

In a world still haunted by war, loss, and ambition, Achilles speaks to something eternal in us all: the longing to leave behind more than ashes—to leave behind meaning.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

Discuss how this moment of intense mourning reshapes Achilles’ motivations and emotional identity. What does his reaction reveal about the nature of heroism, friendship, and vulnerability in Homeric culture?

What is the symbolic significance of the Shield of Achilles, and how does it reflect the themes of the epic as a whole?

Consider Achilles’ decision to return to battle, knowing it will lead to his death. How does this reflect Greek views on destiny? What does it mean for Achilles to embrace his fate rather than flee from it?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 19. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Champion Arms for Battle and covers pages 488-502. In the Wilson translation, it is called A Meal Before Dying and covers pages 463-479.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I think that we should not lose sight of the fact that Achilles bears quite a lot of responsibility for the death of Patroclus. I read somewhere that Greek heroes can be defined by their propensity to cause suffering, both to themselves and to those they care about, and this seems to be a great example.

Not to distract from the discourse about Achilles (which I admit is the most reasonable focus) but Hephaestus has robots made of gold!

Achilles is the first James Dean. As the Eagles said “too fast to live, too young to die.”

I was just reading about the Cypria, a lost epic poem that has some of the prequel stories about Achilles et al. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cypria