Exploring Life and Literature.

“Ah, my friend, if once escaped from this battle we were for ageless and immortal, neither I myself nor you should fight among the foremost, nor should we send you into battle where men win glory; but now, seeing that the spirits of death stand close about us in their thousands, which no mortal may escape nor avoid, let us go on and win glory for ourselves, or yield it to others.”

Dear friends,

Homer’s The Iliad surges with the relentless energy of war, a conflict that ebbs and flows like the tide, carrying warriors to their doom and others to glory. In Book 12, the battle rages around the Achaean wall—a hastily constructed fortification meant to shield the Greek ships from Trojan assault. This moment in the epic underscores the transient nature of human achievement, the inexorable power of fate, and the unyielding determination of warriors.

As the Trojans, led by Hector, press toward the Greek defenses, Homer pauses to offer a prophetic vision of the wall’s eventual destruction. Zeus and Poseidon, gods whose dominion includes the sea and the earth, will one day erase this barrier from existence, washing it away like sand before the waves. This foreshadowing reminds the audience that no matter how grand, human constructions cannot withstand the forces of nature and divine will.

The battle at the wall is fierce, with the Greeks desperately defending their last line of resistance. The Trojans, emboldened by the favor of Zeus, advance relentlessly. A key moment occurs when Hector, the great Trojan warrior, rallies his men and resolves to break through the gates of the Greek defenses. But despite their divine advantage, the Trojans find the wall a formidable obstacle. Unlike previous books where the battle has been fluid, it becomes an extended siege, a test of endurance, strategy, and raw force.

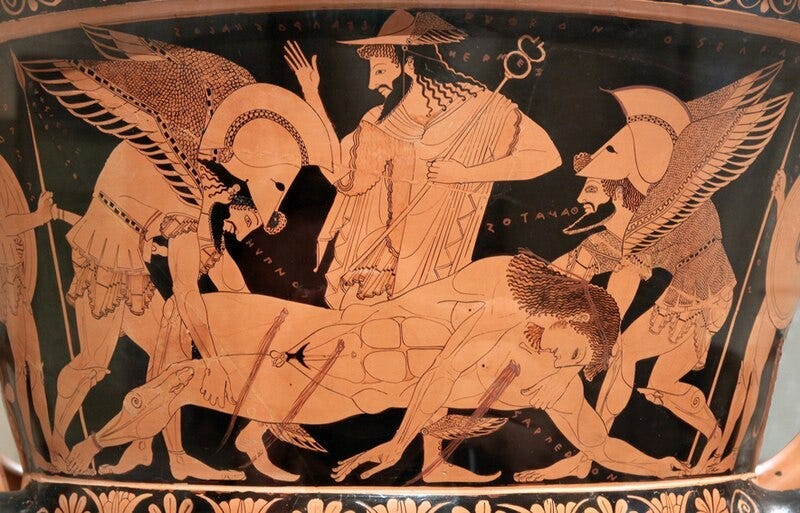

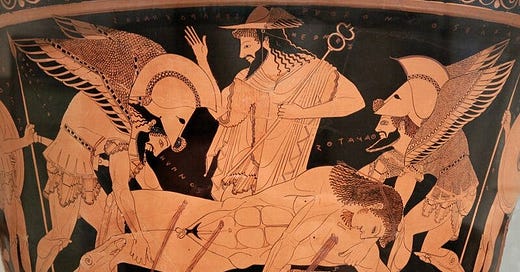

Two notable warriors, Sarpedon and Glaucus, stand out among the Trojan ranks. Sarpedon, son of Zeus, emerges as a figure of destiny and courage. He challenges the Lycians under his command to prove their worth, invoking the heroic code that warriors live by: if they seek honor, they must fight for it with their lives. With divine backing, Sarpedon charges the wall, tearing down its defenses and setting the stage for Hector’s triumph. His speech to Glaucus reveals a fundamental truth of the Homeric world—nobility and privilege come with the obligation to lead in battle, even at the cost of one’s life.

Homer’s imagery here is striking: the wall is not just a physical barrier but a symbol of the Greeks’ last hope, a tenuous grasp on survival in a war where the gods hold ultimate sway. The moment of its breach signals a shift in power. The Greeks, once the aggressors, now find themselves pushed back toward the very ships that brought them to Troy.

With Sarpedon leading the charge, the wall begins to give way. The Greeks fight valiantly, but the combined force of men and fate work against them. The climax arrives when Hector, wielding a massive stone, shatters the gate. Homer emphasizes Hector’s overwhelming strength, comparing him to a storm unleashed upon a quiet landscape. In this moment, Hector is more than a warrior—he is the embodiment of war itself, relentless, destructive, and inevitable.

As the Greeks fall back, panic sets in. The Trojans pour through the breach, and for the first time, the Greek ships stand within reach of Trojan fire. The momentum of the war has shifted dangerously against the Achaeans, foreshadowing greater struggles to come.

The breaching of the Achaean wall is not just about warfare; it speaks to the fragility of human efforts, the nature of power, and the inevitable cycles of rise and fall. Homer’s depiction of the Greek wall reminds us that no human-made structure, whether physical, political, or ideological, is permanent. Just as the wall, hastily built by the Greeks, is doomed to be washed away by the gods, the greatest empires and institutions of our time also face eventual decline. History is littered with once-powerful nations, corporations, and movements that seemed invincible but crumbled. The rise and fall of civilizations, the collapse of financial systems, and even the erosion of personal achievements all echo the fate of the Greek wall.

The Trojans' assault on the wall mirrors the ambition and drive in modern politics, business, and personal struggles. Just as Hector and Sarpedon refuse to be deterred by obstacles, leaders and individuals today push past limits to achieve their goals. Whether in the corporate world, where competition is fierce, or in personal endeavors, where people fight against adversity, the determination displayed in The Iliad finds reflection in contemporary struggles. But Homer also warns us of the consequences of relentless ambition—victory today may lead to downfall tomorrow, just as Hector’s moment of triumph is ultimately overshadowed by his tragic fate.

Sarpedon’s speech to Glaucus highlights a critical lesson: with privilege comes responsibility. Leaders, whether in war, government, or society, must be willing to bear the burdens of their positions. In modern times, this translates to the expectations placed on those in power—CEOs, politicians, activists, and community leaders. The idea that those who reap the benefits of leadership must face its dangers and responsibilities remains as relevant today as it was on the battlefield before Troy.

Book 12 of The Iliad captures a moment of high drama, a clash between determined warriors fighting for their respective causes. Its gripping depiction of battle raises questions about fate, ambition, and the nature of human endeavor. Even though the walls we build today may not be made of stone and earth, they are just as vulnerable to time, ambition, and forces beyond our control. Homer’s epic reminds us that while victory and defeat are fleeting, the courage to face adversity defines us across generations. The echoes of the Greek and Trojan struggle continue to reverberate in our literal and metaphorical battles, shaping how we understand resilience, leadership, and the impermanence of power.

“But when in time the finest of the Trojans fell, and many Achaeans lay dead, and the city's walls were overthrown, and the Argives sailed back home, then Poseidon and Apollo planned to sweep away the great rampart, unleashing the force of rivers that flow from the mountains into the sea.”

In reading The Iliad, especially in Robert Fagles’ evocative translation, we find ourselves immersed in a world of war, honor, and divine will. Books 1-12, comprising nearly half of the epic, present grand themes that continue to resonate across time: the nature of rage, the fragility of human life, the burdens of leadership, and the constant interplay of fate and free will. As we traverse these early books, we are not merely spectators of an ancient conflict but students of its lessons, witnesses to its tragedies, and participants in an enduring conversation about what it means to be human.

From the very first line—“Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles”—Homer sets the stage for one of the most fundamental themes of The Iliad. The wrath of Achilles, provoked by Agamemnon’s arrogance and the loss of his war prize, Briseis, dominates the opening books. His decision to withdraw from battle is not merely personal; it has devastating consequences for the Greek army. Without its greatest warrior, the Achaeans falter, and Trojan advances become more aggressive. Achilles' anger leads to suffering, not just for himself but for his comrades.

In modern terms, this narrative reminds us of the destructive potential of unchecked anger. Whether in politics, personal relationships, or the workplace, pride and stubbornness can lead to conflict with dire consequences. Achilles, blinded by his rage, chooses personal vendetta over communal well-being—an all-too-familiar human failing. The lesson here is one of self-awareness: unchecked emotions can erode alliances and lead to irreversible loss.

In Homeric society, honor (or kleos, the fame one leaves behind) is paramount. Leaders like Agamemnon and Hector struggle to balance personal pride with their responsibilities to their people. Agamemnon’s arrogance and refusal to compromise with Achilles reveal the fragile egos that often underlie leadership. Meanwhile, Hector, perhaps the most honorable figure thus far, fights not for personal glory alone but for his family and city.

The tension between personal ambition and the greater good is timeless. Leaders today must navigate this balance, making decisions that affect the lives of many. Agamemnon’s failures illustrate how self-interest can lead to discord, while Hector’s devotion reminds us of the nobility of service. The modern lesson is clear: true leadership demands humility, responsibility, and a vision beyond oneself.

One of the most haunting aspects of The Iliad is the tension between fate and free will. The gods intervene constantly, but even they cannot alter destiny. The dictates of fate bind Zeus; despite his power, he cannot prevent Patroclus’ death or change the course of the war. This theme forces us to consider our own place within forces beyond our control. How much agency do we truly have? Does fate dictate our lives, or do our choices shape our paths?

This question is as relevant today as it was in Homer’s time. In an age of rapid technological advancement, economic uncertainty, and global crises, many feel caught in forces larger than themselves. Yet, The Iliad suggests that human choice matters even within the constraints of fate. Hector fights, knowing Troy will fall, but he fights nonetheless. We may not control everything in our own lives, but we can control how we respond to challenges.

Books 1-12 provide harrowing depictions of war’s brutality. The battles are graphic, the deaths numerous, and the emotional toll profound. Men die for honor, loyalty, or simply because they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. The humanity of both Greeks and Trojans is on full display, making clear that war is not about abstract heroics but real human suffering.

In today’s world, where conflicts still rage and soldiers continue to fight for causes greater than themselves, The Iliad remains painfully relevant. It asks us to reflect on the true cost of war—beyond politics and rhetoric to the lives altered and lost. The poem does not glorify war; rather, it presents its consequences unflinchingly, urging us to consider the weight of violence and the fleeting nature of life.

Why read an ancient epic today? Because its truths are timeless. Achilles’ rage, Agamemnon’s arrogance, Hector’s duty, and Zeus’ constraints are not relics of the past—they are reflections of our present. As we navigate our own conflicts, personal ambitions, and moral dilemmas, we find echoes of Homer’s warriors in ourselves.

Reading The Iliad in the 21st century is an exercise in self-examination. It forces us to ask: Are we ruled by our tempers? Do we seek honor at the cost of others? Do we recognize the weight of our choices? And ultimately, how do we live knowing that, like the warriors before us, we will be dust one day?

Books 1-12 of The Iliad set the stage for the epic’s climactic events, but they also gave us much to ponder. As we move forward, the lessons of Achilles, Hector, and the gods remain with us, guiding our understanding of literature and life itself.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

How do you feel making it to the halfway point?

Homer foreshadows that the gods will eventually destroy the Achaean wall. What does this suggest about the nature of war and human achievements in the epic? How does this passage contribute to The Iliad’s larger themes of mortality and impermanence?

Sarpedon and Glaucus discuss the responsibilities of leadership and the necessity of fighting for honor. What does this conversation reveal about the heroic code in Greek culture? How does Sarpedon’s reasoning compare to Achilles' views on glory and death?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 13. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Battling for the Ships and covers pages 341-368. In the Wilson translation, it is called The Waves and covers pages 295-325.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

It always struck me that Hector fought competently and cooly for family and city rather than glory (making him one of the more admirable characters in the book), and did it despite the fact that it was all Paris and Helen's shit show. He has one blow up with Paris, but spent remarkably little time chastising their stupidity or cursing fate and casting blame.

We're all actors in a play we can't control. We need to make the best of it. Hector probably does a better job of it than most people would in his situation.

You bring ancient themes into sharp focus for modern readers. I’m especially struck by how you connect heroism and humility, which, in my opinion, is a challenging feat.