Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular essays appear on Tuesdays and Book Club essays on Fridays.*

“Screams of men and cries of triumph breaking in one breath, fighters killing, fighters killed, and the ground streamed blood.”

Dear friends,

In Book 4 of Homer’s The Iliad, titled The Truce Erupts in War, the fragile pause in the conflict between the Achaeans and Trojans shatters under divine intervention and human folly. Following the momentous duel between Paris and Menelaus in Book 3, where Helen's fate appeared poised to decide the war, this chapter marks a swift return to the chaos and inevitability of battle.

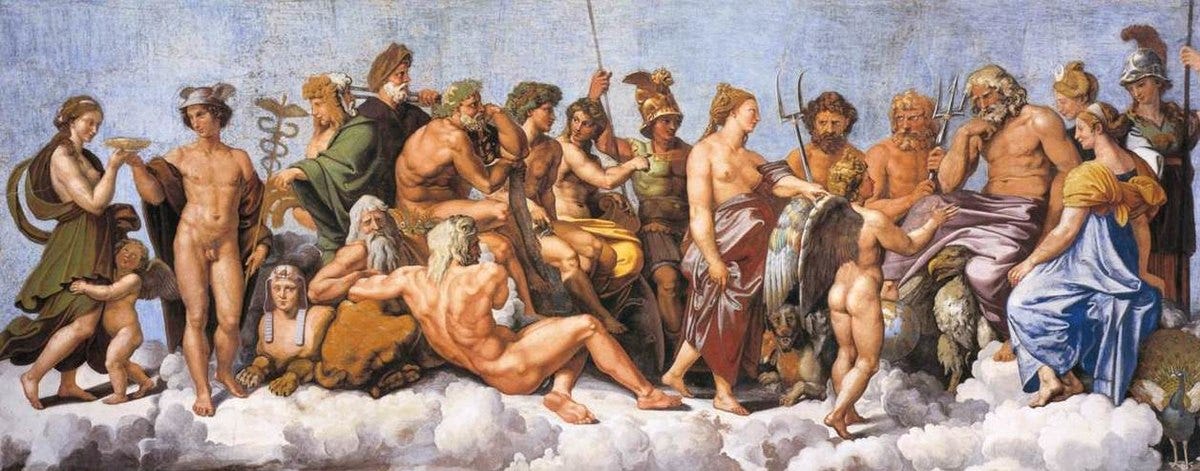

The book begins on Mount Olympus, where the gods convene to deliberate the war's fate. Zeus, ever the arbiter of destiny, proposes a cessation of hostilities, suggesting that the Achaeans return home. However, Hera and Athena vehemently oppose this notion. Their loathing of Troy compels them to advocate for the city's destruction, thus reigniting the conflict. Hera, in particular, persuades Zeus to allow further violence, demonstrating the powerful interplay between divine agendas and mortal suffering.

Athena descends to the battlefield to implement the divine plan. Disguised as a Trojan archer, she manipulates Pandarus, a skilled but impulsive warrior, into breaking the truce by shooting an arrow at Menelaus. The arrow strikes Menelaus, grazing him and drawing blood. Although the wound is not fatal, it serves as a pretext for both sides to return to combat. The truce, tenuous at best, collapses entirely.

What follows is a vivid depiction of the battlefield's descent into violence. Homer employs his signature graphic detail to describe the ensuing chaos, with warriors from both sides clashing in a brutal melee. Key figures from the Achaean and Trojan ranks take to the field, and the narrative shifts rapidly between various combatants, emphasizing the scope and intensity of the struggle.

Homer uses this episode to underline significant themes of the epic, including the fragility of peace and the devastating consequences of divine interference in mortal affairs. The gods, driven by personal vendettas and whims, wield their influence with little regard for the human lives they manipulate. Pandarus, swayed by Athena, becomes a pawn in the gods' larger game, symbolizing the precarious balance of agency and fate.

This chapter also foreshadows the epic's central conflict, where attempts at diplomacy and resolution are repeatedly undermined, both by divine machinations and the inherent flaws of the human characters. The broken truce becomes a microcosm of the larger narrative, illustrating how pride, anger, and vengeance perpetuate the cycle of violence.

In The Truce Erupts in War, Homer masterfully transitions from the relative calm of Book 3 to the ferocity of open combat. This shift heightens the dramatic tension and reinforces the inevitability of war as a central force in the epic. The chapter sets the stage for the relentless carnage to come, reminding readers of the high stakes and the tragic futility of the conflict between the Achaeans and Trojans.

“So the peace agreement struck with sacrifices was shattered by the will of Zeus, as he handed glory to the Trojans and Hector.”

Athena, one of the most revered deities in Greek mythology, stands as a complex figure embodying wisdom, strategy, and martial prowess. Born fully grown and armored from the head of her father, Zeus, after he swallowed her pregnant mother, Metis, Athena is both a paragon of intellect and a formidable warrior. Her duality as a goddess of both war and wisdom is central to her identity, and this duality profoundly shapes her role in the Trojan War as described in Homer’s The Iliad.

Athena is one of the Olympian Twelve and holds a unique position among the gods. Athena represents strategic and disciplined warfare, unlike Ares, the god of brutal and chaotic war. She is the patron of heroes, a protector of cities, and a guide to those who seek her wisdom. Athens, the city named in her honor, was a center of learning and culture, reflecting her influence.

Often associated with the owl, a symbol of wisdom, and the olive tree, a symbol of peace and prosperity, Athena embodies the tension between conflict and harmony. She is also known for her chastity, having taken a vow of eternal virginity, and her independence, a trait that sets her apart from many other gods who are often embroiled in romantic entanglements.

Athena plays a pivotal role in the Trojan War, her involvement rooted in divine politics and personal vendettas. The seeds of her participation are sown during the infamous Judgment of Paris, a beauty contest between Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite. When Paris, a Trojan prince, awards the golden apple to Aphrodite, spurning Athena and Hera, the two goddesses vow vengeance against Troy. Athena's resentment of Paris and the Trojans drives much of her involvement in the conflict.

Athena is firmly aligned with the Achaeans (Greeks) throughout the war, whom she supports with her counsel, martial skills, and divine interventions. As a goddess of strategy, she is instrumental in turning the tide of battles. Athena’s role as a manipulator and strategist is also evident in her interactions with other gods and mortals. In Book 4, she incites Pandarus to break the truce by shooting an arrow at Menelaus, reigniting the war. Her actions are calculated to ensure that the conflict continues, reflecting her determination to see Troy fall. Yet, her interventions are not solely destructive; she also seeks to inspire courage and unity among the Achaeans, fostering discipline and order amid the chaos of war.

Athena’s presence in the Trojan War underscores several key themes in Greek mythology and literature. Her embodiment of both wisdom and war highlights the interplay between intellect and violence, suggesting that even in the pursuit of conflict, strategy, and thoughtfulness are paramount. Her favoritism toward the Achaeans and disdain for the Trojans reveal the gods' deeply personal stakes in human affairs, illustrating the interconnectedness of divine and mortal realms.

Athena's actions also reflect the capricious nature of the gods. While her support often benefits the Achaeans, it comes with a cost: the perpetuation of suffering and death. This duality mirrors the broader theme of the Trojan War as a tragic inevitability, where even the guidance of a wise and powerful goddess cannot avert the devastating consequences of human ambition and divine meddling.

Athena’s role in the Trojan War is emblematic of her character as a goddess who balances intellect and strength, strategy and action. Her interventions shape the course of the war, often tipping the scales in favor of the Achaeans, yet her actions are not devoid of bias or personal vendetta. In Athena, Homer presents a figure who is both inspiring and daunting, a reminder of the profound influence of divine forces in human affairs. Through her, the epic explores the complexities of wisdom, power, and the inexorable pull of fate in the grand tapestry of war and mythology.

As I read this week’s chapter a few different things popped out to me that I thought I would highlight. Let me know your thoughts on these or any others that spoke to you.

How does the role of the gods, particularly Zeus, Hera, and Athena, drive the events in this chapter? Do their actions reflect a sense of justice, or are they motivated purely by personal vendettas? To what extent do the gods’ actions undermine the free will of the mortals? Do you think Pandarus had any true choice when he broke the truce?

The truce is broken with startling ease. What does this suggest about the nature of peace in The Iliad? Do you think peace was ever a realistic outcome? How does this chapter reflect the recurring theme of the inevitability of war? Could anything have stopped the escalation once the arrow was loosed?

Homer vividly describes the battlefield and the breaking of the truce. How does his use of imagery enhance your understanding of the chaos and violence of war? The narrative alternates between the divine realm and the mortal battlefield. How does this structure affect your reading experience?

In a war driven by honor and pride, how does the breaking of the truce reflect on the Achaean and Trojan forces? Does it diminish the honor of either side? Are there modern parallels to the fragility of truces or the manipulation of individuals in conflicts? What lessons, if any, can we draw from this chapter?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 5. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Diomedes Fights the Gods and covers pages 164-194. In the Wilson translation, it is called Gods on the Battlefield and covers pages 97-132.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

There is so much pride and ego in this chapter (and preceding chapters). Both gods, goddesses, and the humans have theirs. They want certain outcomes, and none of them want to "lose face," to use an east-Asian expression. Regardless of the cost, they're willing to do whatever it takes to get the result they want. The Greeks, after all, can't be seen to give up after all these years. Athena and Hera can't give in to Zeus. Zeus can't give in to women, etc. etc. That seems like an interesting theme to dissect.

I would have titled this book "Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned"