Exploring Life and Literature.

"Blood ran like rain from the gaping wounds."

Dear friends,

The Iliad, Book 11, is a pivotal chapter that sets the tone for the continuing conflict between the Achaeans and Trojans. In this book, Homer presents an intense battle narrative, highlighting the bravery and vulnerability of key warriors. The ebb and flow of war is depicted with gripping realism, underscoring themes of power, fate, and mortality. The chapter opens at dawn, with Zeus sending the goddess Strife to rouse the Achaean forces. Agamemnon, the leader of the Achaeans, dons his impressive armor, described in great detail by Homer, symbolizing his role as a powerful warrior-king. Inspired by the gods and fueled by his desire for victory, Agamemnon leads a fierce assault on the Trojans, cutting down many warriors with brutal efficiency. His dominance on the battlefield is so overwhelming that the Trojans are forced to retreat.

However, the fortunes of war are never stable in The Iliad, and despite Agamemnon’s initial triumph, his success is short-lived. Zeus, ever in control of the battle’s balance, allows Hector to reenter the fray. Agamemnon is soon wounded by a spear thrust from a Trojan warrior, compelling him to withdraw from combat. This shift in momentum demonstrates the capricious nature of warfare and the limitations of even the greatest warriors.

With Agamemnon out of the fight, Hector seizes the opportunity to rally the Trojans, launching a counteroffensive that severely pressures the Achaeans. The battlefield becomes a scene of intense chaos, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. Three key Achaean warriors—Diomedes, Odysseus, and Nestor—attempt to turn the tide in this crucial moment. Diomedes, known for his valor, manages to wound Hector with a well-aimed spear, briefly forcing him to retreat. However, Zeus intervenes again, discouraging the Achaeans by sending signs of impending doom.

Odysseus, ever resourceful, fights bravely but is eventually overwhelmed. He is wounded and left vulnerable, his perilous situation illustrating the fragility of human strength in the face of divine will. Meanwhile, Nestor, an aging warrior known for his wisdom, recognizes the dire state of the Achaean forces and urges Patroclus, Achilles’ close companion, to persuade Achilles to rejoin the battle. This moment is particularly significant as it foreshadows Achilles’ eventual return to combat.

The book concludes with the Achaeans in a desperate situation. Emboldened by Zeus’ favor, Hector leads the Trojans closer to the Achaean ships, threatening to set them ablaze. The rising tension in this chapter sets the stage for the dramatic confrontations that follow, particularly Achilles's impending involvement, which will alter the course of the war.

Agamemnon’s role in Book 11 highlights the burdens of leadership. As a commander, he is expected to inspire his troops and lead them to victory, but his authority does not make him invincible. His injury serves as a reminder that even the strongest leaders have limitations and must navigate setbacks. Leaders in modern society face similar struggles in politics, business, or military affairs. They must balance personal ambition with the well-being of their followers, make difficult decisions, and accept that no victory is guaranteed. The unpredictability of war in The Iliad parallels the uncertainty of leadership in today’s world, where success is often fleeting and requires constant adaptation.

The wounding of key Achaean warriors such as Agamemnon and Odysseus underscores the fragility of human strength and the transient nature of power. Regardless of their past successes, no warrior is immune to injury or defeat. This mirrors the reality of human vulnerability in contemporary life. Athletes, soldiers, and even high-achieving professionals experience moments of weakness and setbacks that challenge their endurance. The narrative of Book 11 serves as a reminder that strength is not infinite and that perseverance in the face of adversity is a crucial quality.

One of the most compelling moments in Book 11 is Nestor’s appeal to Patroclus, urging him to convince Achilles to return to battle. This moment emphasizes the power of choice and taking action in critical times. Patroclus faces a decision that will ultimately change the course of the war and his own fate. In today’s world, individuals are often called upon to make choices that have significant consequences—whether in social justice movements, professional careers, or personal relationships. This chapter illustrates how decisions, particularly those made in times of crisis, can shape the future in ways that are not always immediately visible.

The interventions of Zeus throughout the battle reinforce the theme of fate’s dominance over human affairs. Despite the warriors’ best efforts, divine will often dictates their successes and failures. While modern society may not attribute events to the direct influence of gods, people still grapple with the tension between personal agency and external forces beyond their control. Economic downturns, political upheavals, and health crises often remind individuals that some aspects of life are shaped by forces greater than themselves. Like the warriors of The Iliad, modern individuals must learn to navigate a world where control is limited and outcomes are uncertain.

“As a lion charges cattle, calves and heifers grazing in a broad marshland, and snaps their necks, so Agamemnon went through them, slashing heads and limbs.”

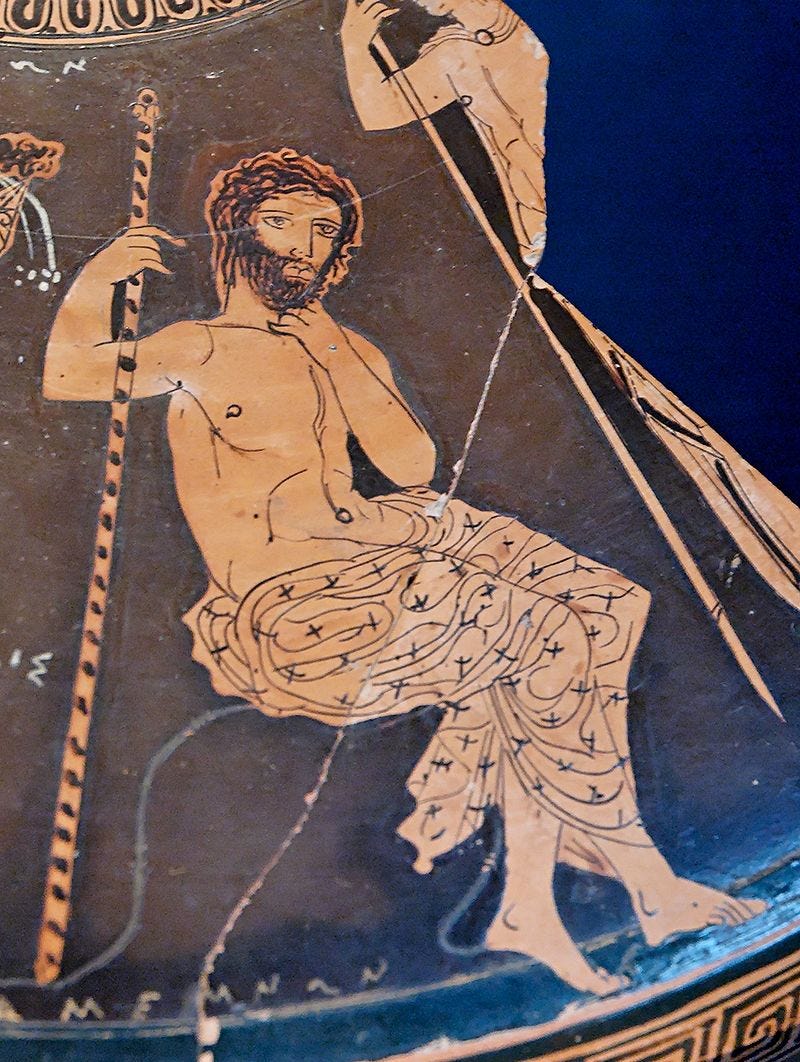

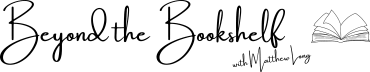

Few figures from ancient history and literature have left as enduring an impact as Agamemnon, the legendary king of Mycenae and commander of the Greek forces in the Trojan War. Agamemnon straddles the line between historical figure and mythological character, appearing in archaeological records and literary epics. His story is one of ambition, leadership, betrayal, and tragedy—a complex narrative that offers insights into the nature of power and the burdens of command.

Agamemnon's legacy is primarily rooted in the Mycenaean civilization, which thrived between 1600 and 1100 BCE in what is now Greece. Mycenae, one of the major centers of this Bronze Age culture, was a powerful city-state known for its military prowess and rich trade networks. Historical records and archaeological discoveries, such as the ruins of Mycenae and the so-called Mask of Agamemnon unearthed by Heinrich Schliemann in the 19th century, suggest the existence of a strong warrior-king who could have served as the model for later legends.

While there is no definitive evidence proving that Agamemnon existed, the society in which he was said to rule provides valuable context. The Mycenaean world was characterized by a hierarchical political system led by kings (wanax) who controlled religious and military matters. These rulers amassed wealth through trade and conquest, securing their authority through strategic alliances and displays of power. The Trojan War, if it took place, likely stemmed from economic and political conflicts between Mycenae and the Anatolian city of Troy, rather than the romantic dispute between Paris and Menelaus’ wife, Helen, as depicted in mythology.

The most famous account of Agamemnon comes from Homer’s Iliad, which portrays him as a powerful yet flawed leader. As the commander-in-chief of the Greek forces at Troy, he is responsible for uniting various city-states under a single cause. Yet, his arrogance and sense of entitlement often lead to internal strife. One of the most defining moments of his character occurs in Book 1 of the Iliad, where he quarrels with Achilles over the captive woman Briseis. His decision to claim Briseis for himself, despite Achilles' protests, results in Achilles withdrawing from battle, almost costing the Greeks the war.

Beyond the Iliad, Agamemnon appears in various other works of ancient Greek literature. In Aeschylus’ tragedy Agamemnon, the first play of the Oresteia trilogy, he is depicted as a returning war hero who meets his demise at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra. This story highlights another significant theme in Agamemnon’s narrative: the consequences of power and the inescapable nature of fate. His sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia to appease the goddess Artemis is one of the most infamous acts associated with him, reflecting the often brutal choices leaders must make in times of war. The play explores the idea of justice and retribution, as Clytemnestra’s vengeance for her daughter's death sets off a cycle of bloodshed that continues in later works.

Agamemnon's leadership is a study in contradictions. On the one hand, he is a capable military commander who unites a fractious coalition of Greek kings. His ability to lead the Greeks in the Trojan War underscores his strategic skills and political acumen. On the other hand, his arrogance, pride, and lack of diplomacy often undermine his effectiveness. The feud with Achilles is a prime example of how personal grievances can interfere with leadership, illustrating the dangers of prioritizing ego over the needs of the collective.

One of Agamemnon’s greatest flaws is his reliance on authority rather than persuasion. He expects unquestioning obedience from his warriors, often alienating key allies. This authoritarian approach can be contrasted with Odysseus, who embodies cunning and adaptability. Agamemnon’s rigidity ultimately contributes to his downfall.

Despite his ancient origins, Agamemnon remains a deeply relatable figure in contemporary leadership discussions. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of power and the complexities of decision-making. Many modern leaders struggle with the balance between authority and diplomacy, ambition and responsibility. His failure to heed wise counsel and his prioritization of pride over practicality mirrors the flaws seen in many historical and contemporary rulers.

Additionally, the themes of sacrifice and duty in Agamemnon’s story resonate with military and political leaders today. His decision to sacrifice Iphigenia for the sake of his army raises difficult ethical questions about the cost of leadership and the moral dilemmas faced by those in positions of power. In a broader sense, Agamemnon’s fate reflects the inevitable scrutiny and consequences that come with leadership—whether through betrayal, political downfall, or personal tragedy.

Agamemnon’s legacy is one of complexity and contradiction. As a historical figure, he represents the warrior-kings of the Mycenaean world, rulers who wielded great power but faced constant challenges to their authority. In literature, he is portrayed as a flawed leader whose arrogance and ambition ultimately lead to his demise. His story immortalized in the Iliad, the Oresteia, and other ancient texts, continues to provide insights into the nature of leadership, power, and human fallibility. Whether viewed as a hero, a tyrant, or a tragic figure, Agamemnon remains one of antiquity’s most compelling characters whose lessons still echo in the corridors of power today.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

Many key Greek warriors (Agamemnon, Diomedes, Odysseus, Machaon) are wounded in this book. What might Homer be suggesting about the fragility of heroism and the nature of war?

How does Homer use imagery and detail to depict the brutality of war in this book? How does this compare to previous battle scenes?

Zeus plays a crucial role in directing the battle, yet individual warriors still seem to have agency. How does Book 11 reinforce or challenge the theme of fate versus free will?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 12. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Trojans Storm the Rampart and covers pages 325-340. In the Wilson translation, it is called The Wall and covers pages 277-293.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

When Homer started comparing Agamemnon’s injury to birth pains, I ducked a little and whispered “don’t go there buddy!” 🤣

You may have discussed this previously, but do you think Homer intended to portray Agamemnon as an unlikeable character (setting aside whether or not he actually existed in history for a minute)? I've always read him as pretty despicable, which I think has to do with the opening of the book, as you mentioned.