Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular newsletters appear on Tuesdays. The Deep Reads Book Club newsletters appear on Fridays. You can find all the book club details at the link below.*

"No man alive has ever escaped his fate, neither brave man nor coward, I tell you— it’s born with us the day that we are born."

Dear friends,

Throughout the first five books, we have witnessed the divine and humanity's interconnectedness. The fickle nature of the pantheon often sways men's fates and the tide of war. Finally, in book six, we find a man who stands on his own without the help of the gods. Hector is devoted to his family, city, and duty while acknowledging that no man can escape his fate.

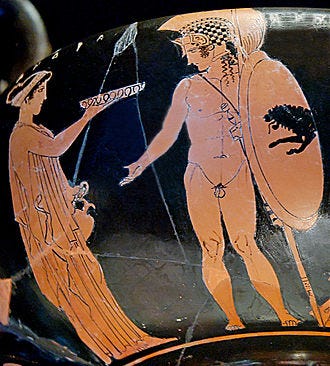

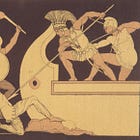

Book 6, Hector Returns to Troy, opens amidst fierce fighting between the Achaeans and Trojans. The Achaean hero Ajax strikes down the Trojan Acamas, and the tide of battle ebbs and flows. The Achaean Diomedes encounters the Trojan Glaucus. Before engaging, they exchanged their lineages, as was customary for warriors. Diomedes learns their ancestors were bound by guest-friendship (xenia), a sacred bond of mutual respect and hospitality. Honoring this connection, they decide not to fight each other. Instead, they exchange armor as a token of their renewed bond, though Glaucus naively trades his gold armor for Diomedes’ bronze, symbolizing a disparity in wisdom.

Meanwhile, Hector, the Trojan prince and leader, returns to Troy to rally support and fulfill his duties beyond the battlefield. He urges the Trojan women, led by his mother Hecuba, to offer sacrifices and pray to Athena in her temple. They implore the goddess to turn the tide of battle, but Athena remains unmoved, steadfastly favoring the Achaeans.

Hector then seeks out his wife, Andromache, in the royal palace. Learning that she is not there, he goes to the city’s battlements and finds her with their infant son, Astyanax. This moment provides a poignant break from the chaos of war as Andromache pleads with Hector to remain in the city and avoid risking his life. She expresses her fear of losing him and the devastating consequences for her and their son if Troy falls. Andromache’s plea reveals her deep love for Hector and the war's heavy toll on families.

Hector, torn between his love for his family and his duty as a warrior, explains his sense of obligation. He acknowledges that his fate is sealed and that no one, not even the bravest of men, can escape death. Despite his profound love for Andromache and Astyanax, Hector feels bound to fight for Troy’s honor and survival. In a touching moment, Hector lifts his son, praying to Zeus that Astyanax will grow to surpass his father in glory and rule over Troy with strength and wisdom.

The tender family scene concludes as Hector bids Andromache farewell, knowing it may be the last time they see each other. Andromache returns home, grieving, while Hector strides back to the battlefield, his tears falling as he steels himself for the fight ahead.

This book juxtaposes the brutality of the battlefield with tender, intimate moments in Hector’s interactions with his family. The shift from violent conflict to Hector’s emotional reunion with Andromache highlights the humanity of warriors and the cost of war on their personal lives. Hector’s love for his wife and son underscores the personal sacrifices that war demands, reminding readers that even the greatest warriors are vulnerable and deeply connected to those they protect. His interactions with Andromache and Astyanax highlight the importance of family and the hope for continuity despite the looming destruction of Troy. His prayer for his son reflects his desire to secure a legacy of honor and strength, even as he acknowledges the fragility of human existence. This contrasts the fleeting nature of life with the enduring significance of reputation and lineage in ancient Greek culture.

Hector embodies the ideal of duty as he prioritizes his role as Troy’s defender over his desires. Despite Andromache’s heartfelt pleas, Hector feels bound by his responsibility to fight for his city and uphold his honor. This tension between personal happiness and public duty reflects a central conflict in heroic literature, emphasizing the sacrifices inherent in leadership and heroism. His poignant acknowledgment of fate reinforces one of the epic’s dominant themes: the inescapable nature of destiny. His acceptance of death’s inevitability—whether in battle or at the gods’ whim—underscores the Greek belief in a preordained order of life. Hector’s courage is amplified by his awareness that his actions will not alter his fate, making his commitment to duty all the more poignant.

Book 6 explores the fragility of peace within the walls of Troy and on the battlefield. Hector’s momentary return to the city serves as a brief respite from the chaos, but returning to the front lines reinforces the inevitability of war’s continuation. The fleeting moments of peace contrast starkly with the ongoing violence, underscoring the transient nature of tranquility in a world ruled by conflict. Here, we see a microcosm of The Iliad’s more significant themes, illustrating the human cost of war, the weight of honor and duty, and the inevitability of fate. It elevates Hector as a tragic hero, torn between his obligations as a warrior and his love for his family, enhancing the epic’s emotional depth and universal relevance.

"So the glorious Hector strode on home but his warm tears wet the dark soil as he scanned the wide plain behind."

Hector, the eldest son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, is presented as the city's greatest warrior and a symbol of its hopes and resilience. However, unlike many other warriors in The Iliad, Hector is not driven by personal glory or divine favor but by duty, love for his family, and loyalty to Troy. These qualities make him both heroic and deeply human.

In Book 6, Hector’s humanity takes center stage. His interactions with his wife, Andromache, and his son, Astyanax, reveal a man deeply aware of the stakes of war—not just for himself but for his family and city. Hector’s vulnerability, expressed through his tears and his prayer for Astyanax, contrasts with the typical image of the invincible warrior, enriching his character with emotional depth.

Hector is a bridge between the battlefield and the domestic sphere, symbolizing the intersection of war and family life. His visit to Troy allows Homer to explore the broader consequences of war, particularly its impact on those who do not fight. His interactions with Andromache and Astyanax reveal his profound love for his family. Yet, his refusal to stay with them highlights the painful sacrifices required of heroes in Greek mythology. This dual role as a warrior and family man underscores the personal costs of his public responsibilities.

He represents the ideal of the protector. His actions are motivated by a desire to shield his city and people, even at the cost of his own life. His speech to Andromache about duty illustrates his understanding of the warrior’s role in maintaining societal order. His awareness of his inevitable death and Troy’s downfall adds a layer of tragedy to his character. Unlike Achilles, who grapples with personal rage and divine destiny, Hector accepts his fate with stoic resolve, embodying the Greek ideal of courage in the face of mortality.

In the realm of myth, Hector epitomizes the Greek concept of areté (excellence), not through sheer combat prowess but through his unwavering sense of duty. He fights not for individual glory but for the collective good, making him a foil to Achilles, who initially withdraws from battle out of personal grievance. Hector’s role reminds readers that heroes are not invulnerable. His humanity, love, and fear make his sacrifices relatable and his story tragic. He represents the cost of heroism, as his choices inevitably lead to personal and communal loss.

While the gods heavily influence many characters in The Iliad, Hector’s actions are primarily driven by human concerns: love for his family, duty to his people, and awareness of his mortality. This human-centric focus makes him unique among the epic’s warriors.

I was most impressed by Hector’s devotion to his family. His role as a husband and father is central to his identity, and his deep emotional connections contrast sharply with the often impersonal motivations of other warriors. Andromache’s plea for Hector to stay with her and their son is a powerful moment that reveals his role as a family man. Her grief at the thought of losing him gives readers a glimpse of the devastating ripple effects of war on loved ones. While tender, Hector’s response emphasizes his sense of responsibility over his desires.

Hector’s interaction with his son, Astyanax, is one of the most touching moments in The Iliad. When Astyanax recoils from Hector’s helmet, it humanizes the warrior, showing the gulf between his public identity as Troy’s defender and his private self as a father. His prayer for Astyanax reflects his hope for a better future for his son, even though he knows it is unlikely. Hector’s love for his family reveals a layer of vulnerability that stands out in the hyper-masculine world of Homeric heroes. It demonstrates that his motivations extend beyond the battlefield, making him more relatable and tragic.

Unlike many warriors in The Iliad, motivated by personal glory (kleos) or divine intervention, Hector fights primarily to protect Troy. He views his role as a defender not as a choice but as an obligation. Hector is not just a warrior; he is Troy's physical and symbolic shield. His presence in the city during Book 6 underscores his responsibility to inspire hope among its citizens. Even as he interacts with his family, he reminds himself of his duty to return to the battlefield. His internal conflict—between his obligations as a protector and his personal life—adds depth to his character. He understands that his decision to fight will likely result in his death, yet he accepts this sacrifice because the survival of his city depends on him. This sense of duty elevates Hector’s heroism from a mere quest for glory to an act of profound selflessness.

Hector’s acceptance of fate and mortality is another key aspect of his identity. While many Greek heroes are driven by the pursuit of eternal renown (kleos aphthiton), Hector’s actions are grounded in the present and the reality of human life. His stoic acceptance of fate sets him apart. Unlike Achilles, who rages against his destiny, or Paris, who shirks responsibility altogether, Hector faces his mortality with courage and resolve. His acknowledgment of death’s inevitability—"No man alive has ever escaped his fate"—underscores the Greek worldview that life is fleeting, and honor lies in how one meets one's end. In his conversation with Andromache, Hector predicts not only his death but also the destruction of Troy and the suffering that will befall his family. This foresight adds a tragic weight to his character, as he fights not with the hope of victory but with the knowledge that his sacrifice is ultimately futile.

Hector’s focus on family, duty, and mortality makes him one of the most relatable characters in The Iliad. His struggles are timeless: balancing professional obligations with personal relationships, facing the inevitability of loss, and striving to leave a legacy despite uncertain outcomes. This universality is why Hector has often been viewed as the heart of The Iliad, embodying the human cost of war in a way that transcends time and culture.

In Book 6, Hector’s character is fully realized. His interactions with Andromache, sense of duty, and poignant awareness of fate encapsulate the essence of his role in The Iliad. He represents a hero torn between two worlds—one of familial love and one of martial obligation—making him one of the epic's most relatable and tragic figures. He is a hero defined by his humanity. His love for his family, dedication to his people, and acceptance of mortality make him a unique figure in The Iliad. While other warriors achieve their heroism through divine favor or personal ambition, Hector’s heroism lies in his selflessness and his ability to prioritize the needs of others over his desires. In this way, Hector is not just a great warrior of Troy; he is a timeless symbol of the complexities of human life and the sacrifices inherent in heroism.

As I read this week’s chapter, I thought I would highlight a few things that popped out to me. Let me know your thoughts on these or any others that spoke to you.

How does Hector’s interaction with his family (Andromache, Astyanax, and Hecuba) reflect his sense of duty to Troy versus his desires?

Andromache pleads with Hector to prioritize his family’s safety over the battle. How does her perspective contrast with Hector’s sense of honor and obligation?

Compare Hector's actions and choices with Achilles in earlier books. How do they differ in their sense of heroism?

How does Homer use imagery and dialogue to heighten the emotional impact of Hector and Andromache’s farewell?

How does this chapter underscore the human cost of the Trojan War, particularly for civilians and families?

Can you draw modern parallels to Hector’s conflict between duty and personal life?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 7. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Ajax Duels with Hector and covers pages 214-230. In the Wilson translation, it is called A Duel and covers pages 155-174.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I was struck in this passage as well, especially Emily Wilson’s introduction which sheds a different light on Hector‘s interactions with his wife that I found compelling. She highlights the struggle h 44 e experiences as one between a duty and an honor that actually causes pain. Without him, he and his wife both know that she will be enslaved and abused. When he says that he is glad he won’t be there to hear her screams, it made me question the relative heroism and protection of what he’s doing. Wouldn’t he be protecting her better if he did not go, especially knowing that his going means his death and her suffering? Yet, the social convention of heroism and fighting pulls just as strongly on him as it does on Achilles. He is more self-aware of this dilema, though.

Hector’s nobility/heroism is lost on me (via modern sensibilities) when he said:

“But as for me, I hope I will be dead,

and lying underneath a pile of earth,

so that I do not have to hear your screams

or watch when they are dragging you away.”