Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular essays appear on Tuesdays and Book Club essays on Fridays.*

“Whoever wins and proves the stronger man, let him take the woman and all her treasures home. Let the rest of us swear a solemn binding oath, friendship sworn and faith inviolate.”

Dear friends,

The book opens with the Trojan and Greek armies preparing for battle on the plains of Troy. Among the Trojans, Paris (also called Alexandros), the prince whose elopement with Helen sparked the war, steps forward, dressed in splendid armor, and challenges the best of the Greek warriors to single combat. Menelaus, Helen’s husband, eagerly accepts the challenge, seeking to reclaim his honor.

However, when Paris sees Menelaus approach, he is struck by fear and retreats into the Trojan ranks. His brother Hector, the leader of the Trojan forces, scorns him, calling him a coward and reminding him of the devastation his actions have caused. Shamed by Hector’s reproach, Paris agrees to fight Menelaus in single combat. This duel is proposed as a means to end the war, with Helen and the wealth Paris took from Sparta as the stakes.

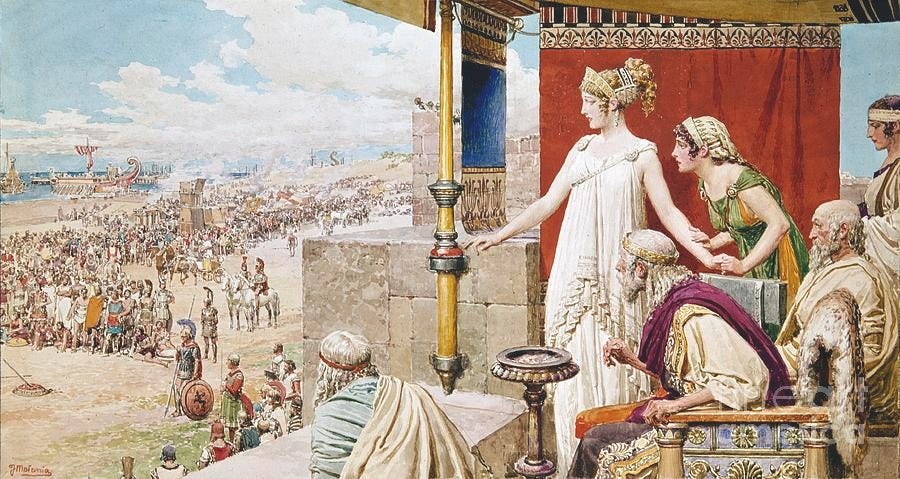

Meanwhile, in the city of Troy, Helen is summoned by Iris, the messenger goddess, disguised as an old friend. Iris urges Helen to watch the duel from the city’s walls. As Helen makes her way to the battlements, she is described in glowing terms, her beauty captivating all who see her. She joins Priam, the Trojan king, and the elders of the city at the walls overlooking the battlefield.

Helen identifies the Greek warriors below at Priam's request, pointing out Agamemnon, Odysseus, and Ajax. Her descriptions of the warriors are tinged with sorrow and longing as she recalls her life in Sparta and the events that led to her current predicament. Helen’s self-awareness and regret are evident in her dialogue; she laments her role in the war and expresses a desire for death to escape her shame.

On the battlefield, the terms of the duel are agreed upon: the winner will claim Helen and her wealth, and the war will end. Paris and Menelaus begin their combat, with Menelaus initially gaining the upper hand. Paris is clearly outmatched, and when Menelaus seizes him by the helmet, dragging him across the battlefield, it seems the duel will end decisively in the Greek king’s favor.

However, the gods intervene. Aphrodite, who favors Paris, shatters the strap of his helmet and spirits him away from the battlefield in a veil of mist. She transports him back to his bedroom in Troy, ensuring his safety.

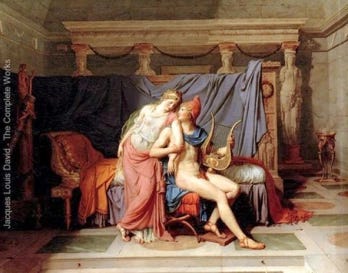

Aphrodite then summons Helen to Paris’s chambers, where she attempts to coax Helen into reuniting with him. Helen resists at first, rebuking Aphrodite for her meddling and expressing disdain for Paris’s cowardice. However, under the goddess’s influence, she ultimately returns to Paris. In their encounter, Helen’s mixed emotions are clear—she despises Paris’s weakness but remains bound to him by the gods and her circumstances.

Back on the battlefield, Menelaus searches for Paris, eager to finish the duel, but the Trojans are unable to find him. The absence of a resolution leaves the truce between the two sides in limbo, and the war is set to continue.

Some say a host of horsemen, others of infantry and others of ships, is the most beautiful thing on the dark earth but I say, it is what you love Full easy it is to make this understood of one and all: for she that far surpassed all mortals in beauty, Helen her most noble husband Deserted, and went sailing to Troy, with never a thought for her daughter and dear parents. — Sappho, fragment 16

Helen of Troy occupies a unique position as both the catalyst of the Trojan War and a symbol of its tragic futility. Her beauty, famously described as “the face that launched a thousand ships,” serves as a focal point for the epic’s exploration of human passions, divine manipulation, and the devastating consequences of conflict. While Helen’s presence looms large, her role is often misunderstood, especially in contrast with other female figures in the poem, such as Andromache and Hecuba. Together, these women illuminate the interplay of agency and fate, the human cost of war, and the complexity of gendered experiences in a patriarchal world.

Helen’s background is steeped in divine and mortal intrigue. As the daughter of Zeus and Leda, Helen’s beauty is both a blessing and a curse, destined to incite chaos. Married to Menelaus, the King of Sparta, Helen’s elopement—or abduction, depending on the source—with Paris, the prince of Troy, becomes the immediate pretext for the Greeks’ expedition against Troy. Yet, the Iliad portrays Helen as more than a passive object of desire or a mere plot device. In Book 3, Helen Reviews the Champions, she stands on the walls of Troy, identifying Greek warriors for King Priam and the Trojan elders. This scene offers a rare glimpse into her perspective: Helen expresses deep shame and regret, calling herself a “hateful creature” and lamenting the role she has played in the war.

Helen’s portrayal is strikingly ambiguous. On one hand, she acknowledges her responsibility, showing self-awareness and remorse. On the other hand, she attributes her actions to the gods, reflecting the Iliad’s broader theme of divine interference in human affairs. This duality makes Helen a complex figure—both a victim and an agent of her fate.

The contrast between Helen and some of the other women in this epic poem is quite stark. In future chapters we will meet Andromache, Hector’s wife, and Hecuba, Queen of Troy and Hector’s mother. Where Helen’s beauty and allure symbolize the external cause of the war, Andromache represents its personal and domestic consequences, while Hecuba embodies the wisdom and suffering of a generation witnessing the destruction of their city and family. We will see that Helen’s grief is introspective and tinged with guilt, Andromache’s is rooted in tangible loss, and Hecuba, in her grief, represents the endurance of women who must survive and bear witness to war’s horrors.

Despite their differences, Helen, Andromache, and Hecuba share common threads that deepen the tragedy of the Iliad. All three women are constrained by a patriarchal society and divine forces, yet they respond to their circumstances in unique ways. Helen’s beauty and its destructive allure raise questions about the price of desire and the fragility of human bonds. Andromache’s plight highlights the personal stakes of war, emphasizing the loss of love and family. Hecuba’s suffering underscores the generational toll of violence, particularly on women.

Together, these women’s stories reflect the Iliad’s exploration of the interplay between agency and fate. Helen’s introspection, Andromache’s pleas, and Hecuba’s lamentations reveal the diverse ways women experience and respond to war. While the men of the Iliad fight for glory and honor, the women bear the emotional and personal burdens, reminding us of the true cost of conflict.

Helen of Troy remains one of the most enigmatic figures in Greek literature, embodying the complexities of beauty, agency, and suffering. Her role in the Iliad, when viewed alongside Andromache and Hecuba, reveals the multifaceted experiences of women in a world dominated by war. Through their stories, Homer not only humanizes the epic’s grand themes but also gives voice to those who endure its consequences. Helen’s enduring legacy lies in her ability to evoke empathy and provoke reflection, reminding us that behind every myth lies a deeply human story.

As I read this week’s chapter a few different things popped out to me that I thought I would highlight. Let me know your thoughts on these or any others that spoke to you.

Helen is judged and valued primarily for her appearance. How does society today place similar pressures on people, particularly women, to conform to standards of beauty or success? How can we resist these pressures?

Helen’s alienation from both sides of the conflict raises questions about belonging. What creates a sense of belonging in our lives? How do we find community in challenging circumstances?

The gods in the Iliad often manipulate human affairs for their own amusement or agendas. How does this reflect the way systems of power or authority shape our choices today?

Helen expresses guilt and shame for her role in the war, calling herself a “hateful creature.” How do we cope with feelings of guilt in our own lives? What strategies help us take responsibility without being overwhelmed by regret?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 4. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Truce Erupts in War and covers pages 145-163. In the Wilson translation, it is called First Blood and covers pages 75-96.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Thoughts after a long walk:

Helen’s beauty is described as awful. It makes men mad with love, lust, will to possess. It gives her great power but no agency. I recently watched the movie Parthenope beautifully set in Naples which explores how a woman’s beauty has influenced her life - my interpretation of the movie is that she chose to not rely on her beauty for her life’s purpose - but that means she had the ability to choose which most of the characters in the Iliad do not given the interfering gods. Free will becomes a question in the Iliad as much as in the bible or for that matter modern neuroscience.

I really like your question about belonging. In the modern world many, if not most people have a foot in many camps without delving into the fraught question of identity. On a long walk this morning it occurred to me that belonging is not an either/or - dichotomy. This also depends on availability of choice and free will. You can choose to belong by adapting or learning new cultures, you can leave a family structure where you do not belong, you can question whether your feelings of not belonging may not be true - CBT style and you can even use your sense of being an outsider to make really good comedy - see most funny stand-up. Helen was also a demi-god as are other characters in the Iliad, including Achillies and there is a sense of their being outside events despite being protagonists at the same time.

One bit I found interesting was the sacrifice of the goats. The ceremony and shared prayer really brought home the point that these are the same people from the same culture, essentially, making their war seem even more futile and tragic.