Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular newsletters appear on Tuesdays. The Deep Reads Book Club newsletters appear on Fridays. You can find all the book club details at the link below.*

"The rest of the warlords of all Achaea’s forces slept the whole night long, overcome by gentle sleep, but not the lord of men, Agamemnon— the sweet embrace of sleep could not hold him, his mind kept churning, seething."

Dear friends,

Homer’s The Iliad is an epic steeped in grandeur, honor, and the unrelenting brutality of war. Yet, nestled within its sweeping battles and godly interventions is Book 10, a departure from the formal structure of daytime warfare. Known as the Doloneia, this book shifts from the clashing of armies to the shadows of the night, where espionage and deception take precedence over brute strength. Through its depiction of Odysseus and Diomedes’ covert mission and the fate of the hapless Trojan spy Dolon, Book 10 presents a moment of tension, strategy, and merciless cunning.

As night descends upon the battlefield, the Greek forces find themselves in dire straits. Hector and the Trojans, bolstered by Zeus, have gained momentum, forcing the Achaeans into a defensive position. In response to this crisis, Agamemnon and Menelaus, unable to sleep, convene a council of Greek leaders. Nestor, the wise and experienced orator, suggests a bold course of action: send scouts into the Trojan camp to gather intelligence. This suggestion is quickly met with approval, and the seasoned warrior Diomedes volunteers for the perilous mission, selecting Odysseus as his companion. The two heroes set out into the night, embodying Greek ingenuity and courage.

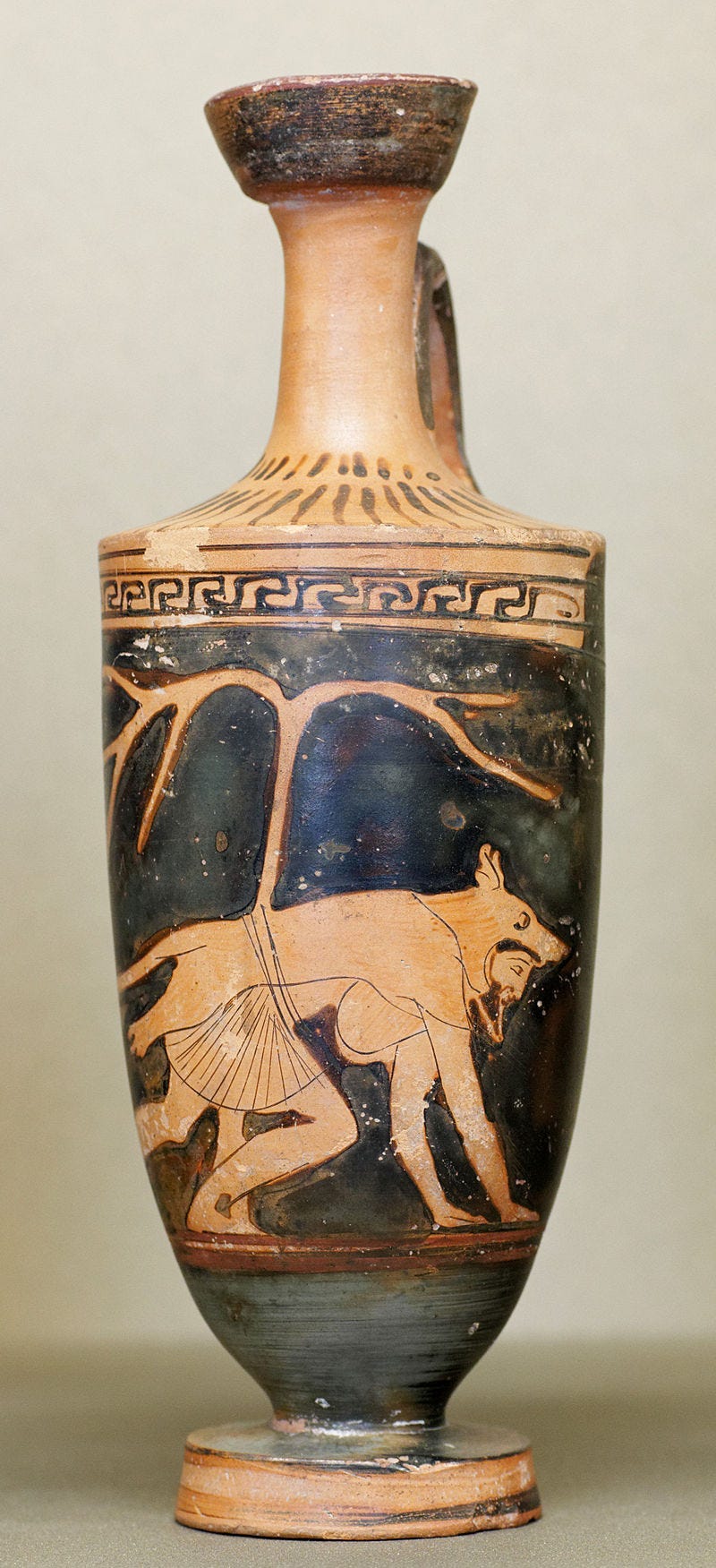

Meanwhile, across the battlefield, Hector also recognizes the advantages of intelligence. He calls upon Dolon, a lesser-known but eager Trojan, who offers to infiltrate the Greek camp in exchange for the prize of Achilles’ horses. Unlike Odysseus and Diomedes, Dolon is unskilled in war; he is a scout, not a warrior. Dressed in wolf skin and a weasel cap, he sets off toward the Greek ships, but his mission is doomed before it even begins.

Odysseus and Diomedes, moving like specters in the darkness, intercept Dolon with cunning precision. Rather than killing him outright, they use psychological manipulation, terrifying him into revealing Trojan secrets. Dolon, desperate to preserve his life, divulges critical information about the Trojan camp, including the locations of key allies and weak points in their defenses. Once he has exhausted his usefulness, Odysseus and Diomedes show no mercy; Diomedes swiftly beheads him, demonstrating the Greeks’ ruthless pragmatism.

Armed with Dolon’s intelligence, the two Achaean warriors do not return immediately to their camp. Instead, they exploit their newfound knowledge and launch a raid on the Thracian camp, an allied force of the Trojans. There, they slaughter King Rhesus and his men in their sleep, further crippling Trojan strength. The Greeks also steal Rhesus’ prized horses, adding insult to injury. This act of calculated brutality underscores the nature of war in The Iliad: honor and glory may be central themes, but so too are deceit and mercilessness. Their mission accomplished, Odysseus and Diomedes return to the Greek camp victorious, their cunning and violence ensuring a tactical advantage in the battles to come.

Book 10 stands apart from the rest of The Iliad in its emphasis on espionage and night raids rather than open conflict. It serves as a reminder that war is not fought solely on the battlefield in daylight; strategy, deception, and psychological warfare play just as crucial a role in determining victory. The contrast between Odysseus and Diomedes’ success and Dolon’s failure highlights the stark realities of experience versus naivety, courage versus desperation. Moreover, the Greeks’ actions in this book expose the darker side of heroism: a hero is not just a warrior with strength but one who can manipulate, deceive, and kill without hesitation when the moment demands it.

Though set in a world of gods and warriors, the themes of Book 10 resonate powerfully in our own time. In today’s geopolitical climate, espionage remains an essential tool of warfare and diplomacy. Nations invest vast resources in intelligence gathering, employing tactics not unlike those of Odysseus and Diomedes. Information remains a critical advantage, and as in The Iliad, the one who possesses it often dictates the course of battle—whether that battle is fought with weapons or in cyberspace.

The psychological manipulation seen in Book 10 is also reflected in contemporary strategies of war and politics. Just as Odysseus and Diomedes trick Dolon into revealing secrets before discarding him, modern intelligence operations rely on deception, misinformation, and psychological tactics. The ethical dilemmas surrounding espionage, including its necessity and its moral cost, remain as relevant today as they were in Homer’s time.

Additionally, Book 10 sheds light on the nature of leadership. Agamemnon, rather than relying solely on brute force, recognizes the need for intelligence and strategy. Leaders today, whether in military, political, or corporate spheres, must also balance strength with cunning. Success is rarely achieved through force alone; strategy, knowledge, and adaptability often prove more decisive.

Finally, the merciless efficiency with which Odysseus and Diomedes operate raises questions about morality in warfare. The lines between heroism and brutality blur, challenging us to consider whether ends justify means. This debate extends beyond the battlefield into modern discussions on military ethics, cybersecurity, and political maneuvering.

Book 10 of The Iliad offers a rare glimpse into the underbelly of war, where honor gives way to cunning, and battle is waged not just with swords but with deception and intelligence. The fates of Dolon, Rhesus, and his men serve as cautionary tales about the brutal realities of conflict. Though the world has changed since Homer’s time, the themes of espionage, strategy, and the moral ambiguities of war remain strikingly relevant. Whether in ancient Troy or the modern world, those who master information and deception often hold the keys to victory.

"We must send out our best to scout the enemy lines. Any man with a daring heart, let him volunteer!"

The Iliad is filled with warriors, gods, and kings whose actions shape the fate of the Trojan War. Among these figures, Nestor, the aged king of Pylos, stands out not for his prowess in battle but for his wisdom, experience, and rhetoric. While Achilles rages and Hector fights with valor, Nestor offers counsel, attempting to guide the younger warriors through the war with prudence and strategy. His role in The Iliad is essential, providing a contrast to the rashness of youth and serving as a reminder of the values of a bygone heroic age. To understand Nestor’s significance, it is necessary to examine his background, his contributions to the epic, and the ways in which he embodies the virtues of wisdom and experience.

Nestor is the son of Neleus and Chloris, belonging to a noble lineage that traces back to the gods. His father, Neleus, was a son of Poseidon and ruled over Pylos, a kingdom in the southwestern Peloponnesus. According to mythology, Neleus and his sons were attacked by Heracles, and all but Nestor were slain. This early survival reinforced Nestor’s legendary status as a hero blessed with longevity and divine favor.

As a young man, Nestor proved himself in combat, fighting in numerous battles before the Trojan War. He participated in conflicts against the Arcadians and aided the Lapiths in their war against the centaurs. His past exploits establish him as a warrior of great repute, though by the time of The Iliad, he is no longer at the height of his physical strength. Instead, he is defined by his ability to advise and persuade. Despite his advanced age, he remains an influential figure among the Achaeans, valued for his wisdom rather than his martial prowess.

In The Iliad, Nestor serves as a counselor to the Achaean leaders, offering advice and urging unity among the warriors. His speeches, often lengthy and reflective, invoke the past as a model for the present, urging the younger generation to act with honor and discipline. His primary role in the narrative is that of an elder statesman, guiding the warriors through their conflicts and attempting to mediate disputes.

One of Nestor’s earliest contributions to the story occurs in Book 1, during the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles. As the two warriors argue over the fate of Briseis, Nestor intervenes, urging them to reconcile. He reminds them of past heroes and the importance of unity in war, emphasizing that internal discord will only weaken their cause. While neither Agamemnon nor Achilles heeds his counsel, Nestor’s intervention highlights his role as a voice of reason amid the chaos of war.

Throughout the epic, Nestor continues to offer strategic and diplomatic advice. In Book 2, he suggests the organization of the Greek army into units based on their regions, ensuring better coordination in battle. In Book 7, he proposes a temporary ceasefire to allow for the burial of the dead, demonstrating his concern for both the living and the fallen. His counsel extends beyond strategy—he also encourages younger warriors like Diomedes and Patroclus, inspiring them to rise to greatness.

Nestor’s importance in The Iliad extends beyond his strategic contributions; he represents the ideal of wisdom in contrast to the impulsive nature of younger warriors. He often recounts stories from his youth, drawing comparisons between past heroes and the current generation. While some of these speeches may seem overly nostalgic or self-aggrandizing, they serve an important narrative function by linking the present conflict to a broader heroic tradition. Nestor’s recollections remind the warriors—and the audience—of the values that define heroism: courage, loyalty, and respect for the gods.

His role as a mediator is particularly crucial in a war driven by personal grievances and unchecked emotions. The tension between Achilles and Agamemnon, Hector’s personal struggles, and the tragic fate of many warriors could all benefit from Nestor’s wisdom, yet his advice is often ignored. This disregard for wisdom in favor of pride and passion underscores one of the epic’s central themes: the tension between reason and emotion in the pursuit of glory.

Nestor’s interactions with other characters further illustrate his role as a mentor and guide. He has a particularly close relationship with Patroclus, encouraging him to step into Achilles’ place when the latter withdraws from battle. This encouragement plays a pivotal role in the narrative, as Patroclus’ eventual death at the hands of Hector leads to Achilles’ return to the battlefield. Nestor’s words set this chain of events in motion, highlighting the far-reaching impact of his advice.

His relationship with Diomedes is also significant. When Diomedes hesitates to engage in battle, Nestor invokes the memory of his own youthful exploits, inspiring the young warrior to act with greater confidence. This interaction reflects the generational divide in the epic—Nestor embodies the wisdom of the past, while Diomedes represents the future of Greek heroism.

Even among his peers, Nestor’s wisdom is acknowledged. While Agamemnon is often stubborn and Achilles is consumed by pride, both recognize Nestor’s authority as an elder. However, their failure to fully embrace his counsel contributes to the tragic trajectory of the war.

Nestor’s significance extends beyond The Iliad. In The Odyssey, he remains a respected figure, hosting Telemachus when the young man seeks news of his father, Odysseus. His continued presence in Greek mythology reinforces his role as a bridge between generations, preserving the wisdom of the past for those who will shape the future.

His portrayal in The Iliad serves as a reminder of the value of experience and the consequences of disregarding wise counsel. While the epic celebrates the heroism of warriors like Achilles and Hector, it also acknowledges the necessity of figures like Nestor, who provide balance and perspective. His speeches, though sometimes long-winded, offer insights into the nature of leadership, the importance of unity, and the lessons of history.

Nestor’s role in The Iliad is crucial, not as a warrior, but as a sage whose wisdom is meant to guide the younger generation. His presence underscores one of the epic’s key themes: the tension between youthful impetuosity and the wisdom of age. Though often ignored, his words carry profound significance, serving as both a warning and a lesson. Through Nestor, Homer emphasizes that war is not only fought with swords but also with wisdom, strategy, and diplomacy. His character reminds us that in times of conflict, the voices of experience should not be disregarded, for they offer the insights necessary to navigate the complexities of both war and life.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

How does Book 10 explore the theme of cunning versus brute force in war? In what ways does intelligence play a role in the Greeks' strategy?

Some scholars believe Book 10 was a later addition to The Iliad. Does it feel different in tone or style from the surrounding books? Why or why not?

In modern warfare, intelligence and espionage play a critical role. How does the Dolon episode relate to contemporary ideas about reconnaissance and military ethics?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 11. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Agamemnon’s Day of Glory and covers pages 296-324. In the Wilson translation, it is called Wounds and covers pages 245-276.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

I fear that our modern day Nestors are being pushed aside at a time when they are needed most. I see both modern Dolons ready to give up the game and Diomedeses willing to blur moral boundaries.

As far as being a later addition, that is interesting, but probably harder to tell from a translation rather than source texts. It definitely felt like a breather but not necessarily out of place.

I was also curious where these guys were getting lion and leopard pelts? Were there trade routes to subsaharan Africa at the time?

I think Emily Wilson's note about Book X being a later addition sums it up well (as do most of her notes). On the one hand, she points out that Book X doesn't advance the main plot, the "night raid in which the victims are taken unawares" is not typical, and even since ancient times it was believed to have been a later addition. On the other, "raiding adventures" and the story of Rhesus predate the Iliad. Apparently there was a tradition that if Rhesus and his horses drank from the Xanthos they would become immortal.

A modern study found that the language is more like the Odyssey than the rest Iliad (one element of the language difference that survives translation is that the speeches are much shorter than elsewhere, especially when Dolon is caught). Nevertheless, the writing is authentically Homeric Greek rather than later Classical era Greek, with the conclusion that it must have been added shortly after composition of the unquestioned books.

So much of the killing here seems at odds with the morality elsewhere. Diomedes kills Dolon as he's attempting to supplicate himself even though Dolon's offer of ransom seems like a reasonable offer. I could see an argument (though hypocritical) that by spying he has given up an expectation of normal dealing. Regardless Diomedes's aristeia among sleeping soldiers feels hollow.

I enjoyed the deep dive on Nestor. He has a moment of almost comic relief when he complains to Agammemnon that Menelaos should be up doing this work and keeps on talking until Agamemmnon gets a chance to explain it.