Exploring Life through the Written Word

“I would die of shame to face the men of Troy and the Trojan women trailing their long robes if I would shrink from battle now, a coward.”

Dear friends,

Book 22 of The Iliad marks one of the poem’s most emotionally charged and climactic moments. The long-anticipated confrontation between Achilles and Hector finally unfolds before the walls of Troy. This pivotal episode distills the essence of Homeric heroism: the confrontation with death, the pursuit of honor, and the complex interplay of human pride and divine will.

The book opens with the Trojans retreating behind the city walls after the brutal events of Book 21. Only Hector remains outside, stationed at the Scaean Gates. He is determined to stand his ground despite the pleas of his family. Priam, Hector’s father and king of Troy, begs his son not to confront Achilles, knowing that the Greek warrior’s wrath is fueled by the death of Patroclus. Priam appeals not only as a king but as a father, reminding Hector of the devastation his death would bring to Troy and to his own household.

Hecuba, Hector’s mother, also entreats him, offering her breast in a desperate maternal gesture that recalls the intimacy of infancy, emphasizing the tragic dissonance between Hector the son and Hector the warrior. Yet Hector, torn between the demands of duty and the instinct for survival, cannot bring himself to retreat. He is caught in a psychological limbo: to return within the walls would be an act of shame after his earlier encouragements to the Trojan army, but to face Achilles might mean death. This hesitation underscores the fatal burden of honor in Homeric society.

Meanwhile, Achilles, aflame with fury and grief over Patroclus’ death, approaches like a force of nature. Homer likens him to a star, a blazing light that spells doom. When Hector finally sees Achilles, he loses his nerve and flees. What follows is a gripping chase around the walls of Troy, with the gods watching as spectators. Three times they circle the city—an image rich in symbolic meaning. The chase evokes not only the futility of trying to outrun fate but also the circularity of time, of life and death, of war and its aftermath.

At this moment, Zeus weighs the fates of Achilles and Hector on his golden scales. Hector’s doom descends, and Apollo, who had until now protected Hector, abandons him. Athena, on the other hand, descends to assist Achilles by tricking Hector. Disguised as Deiphobus, Hector’s brother, Athena encourages Hector to stop fleeing and turn to fight.

Reassured by what he believes is his brother’s support, Hector faces Achilles. The duel is swift and brutal. As they face off, Hector proposes a pact: that whichever warrior falls, the victor will return the body to the vanquished’s family. Achilles refuses, declaring that no oaths can exist between lions and men—a chilling rejection of any semblance of mutual respect.

The fight ends decisively: Achilles drives his spear into Hector’s neck, though not fatally at first. As Hector lies dying, he pleads once more for his body to be returned to his family for a proper burial. Achilles, unmoved, taunts him and declares his intention to let the dogs and birds devour Hector’s corpse.

After Hector dies, Achilles strips the body of his armor—ironically, the very armor that Hector had taken from Patroclus. Achilles then pierces Hector’s heels, ties his body to his chariot, and drags it around the walls of Troy. This desecration is met with horror by Priam and Hecuba, and especially by Andromache, Hector’s wife. Her grief-stricken lament closes the book with a powerful elegy not only for Hector but for the doomed city of Troy itself.

Image

Book 22 of The Iliad is arguably the poem’s emotional and narrative apex. In this chapter, Homer presents a profound meditation on mortality, honor, vengeance, and the fragility of human dignity. Its resonance across the centuries is rooted in the universal nature of the dilemmas it dramatizes. The action is not only a heroic confrontation but also a deeply human tragedy.

Hector embodies the tragic hero in its fullest sense. He is a character caught between competing loyalties—his duty to the city, his role as a son and father, and his own instinct for survival. His decision to stay and fight, rather than seek shelter, is shaped by the code of kleos, or glory, that defines Homeric masculinity. Hector knows that his reputation will suffer irreparably if he avoids combat. Yet his hesitation reveals that honor is not simply a motivator but also a burden. As he reflects to himself:

“Now my spirit stirs me to meet Achilles, face-to-face, / though he’s far the stronger” (Fagles, 22.129–130).

This moment of introspection shows Hector as a deeply aware character. He knows he is likely to die, but to die with honor is preferable to living in shame. This logic, tragic and beautiful, remains one of Homer’s lasting contributions to the literature of the heroic code.

In contrast, Achilles is not merely a hero in this chapter—he is wrath incarnate. His humanity seems eclipsed by the magnitude of his grief. The death of Patroclus has hollowed him out, replacing his earlier ambivalence toward the war with a single-minded desire for revenge. Yet his behavior toward Hector's body—his rejection of Hector’s plea and the desecration of the corpse—reveals a moral rupture. Achilles, once perhaps sympathetic in his disillusionment with Agamemnon, now crosses into the realm of the inhumane.

Book 22 continues the motif of divine manipulation and fatalism. Athena’s deception of Hector is especially troubling, as it raises questions about the justice of the gods. Hector’s fate was sealed not solely by his own choices but by divine intervention. This reinforces a central Homeric theme: that mortals are playthings of the gods, and that fate is inexorable.

Zeus' weighing of the fates—his golden scales tipping against Hector—is a striking image. It brings to mind the ancient idea of moira, the portion or lot that each person must receive. Even the gods submit to fate in Homer’s universe, though they actively hasten or delay its fulfillment.

Yet for all its fatalism, Homer’s narrative preserves the dignity of human struggle. Hector’s resistance, though doomed, is noble precisely because it is conscious. His final moments are not a resignation but a confrontation—he knows he will die, but he meets death with open eyes.

The laments of Hecuba, Priam, and Andromache provide some of the most poignant moments in the poem. They humanize Hector beyond his role as a warrior. Andromache’s grief, in particular, is not just for her husband but for their son, for the future that will never be. Her words are filled with pathos:

“You, my husband, you’ve lost your life so young … / and left me a widow in our halls!” (Fagles, 22.546–547).

This lament returns the epic to its most human dimension. While Achilles and Hector contend with gods and fate, the aftermath is felt most deeply by the women and children. In this way, Homer critiques the heroic ideal, showing that the price of glory is often borne by the innocent.

Book 22 speaks across time not because of its divine trappings or epic scale but because it captures essential truths about the human experience.

First, the tension between duty and self-preservation, so vividly dramatized in Hector’s decision, resonates in every context where individuals are asked to make sacrifices for a greater cause. Soldiers, activists, first responders, and even whistleblowers live with these same ethical dilemmas. The moral courage to face danger despite fear, and the burden of honor, remain relevant.

Second, Achilles’ wrath—and the way grief can deform one’s humanity—also speaks to modern readers. Trauma, when left unchecked, often gives way to vengeance or emotional desolation. Achilles does not simply kill Hector; he desecrates his body, violating the warrior code that demands respect for the dead. In an age where revenge narratives pervade media and politics, this episode serves as a sobering meditation on the corrosive power of unbridled anger.

Third, the portrayal of Hector’s family, especially Andromache, brings the consequences of war into sharp relief. In contemporary times, civilians often suffer the most in conflicts they did not start. Andromache’s voice reminds us that every fallen soldier is also a husband, a father, a son—someone whose death leaves a wake of grief.

Finally, the gods’ intervention—and the suggestion that humans are caught in forces beyond their control—mirrors modern anxieties about systems of power. In today’s world, many people feel trapped by political, economic, or social structures that seem to determine their fate. Hector’s doomed resistance speaks to the dignity of striving even when the odds are impossibly high.

Book 22 of The Iliad is not just the story of a duel; it is a meditation on what it means to live and die with purpose. Hector’s courage, Achilles’ rage, the gods’ interventions, and the lamentations of those left behind coalesce into a powerful statement about human nature. The themes of honor, grief, fate, and moral complexity transcend time and culture, remaining relevant to this day.

Even today, in a world far removed from the bronze-speared battlefields of ancient Troy, the questions raised in this chapter remain urgent: What is the cost of honor? Can vengeance ever be just? How do we grieve, and what do we owe the dead? And perhaps most importantly: in the face of inevitable loss, how do we preserve our humanity?

In the death of Hector, Homer gives us not just the end of a hero, but the enduring echo of what it means to be human in the midst of war, suffering, and the fragile hope for peace.

“There are no binding oaths between men and lions— wolves and lambs can enjoy no meeting of the minds— they are all bent on hating each other to the death. So with you and me. No love between us.”

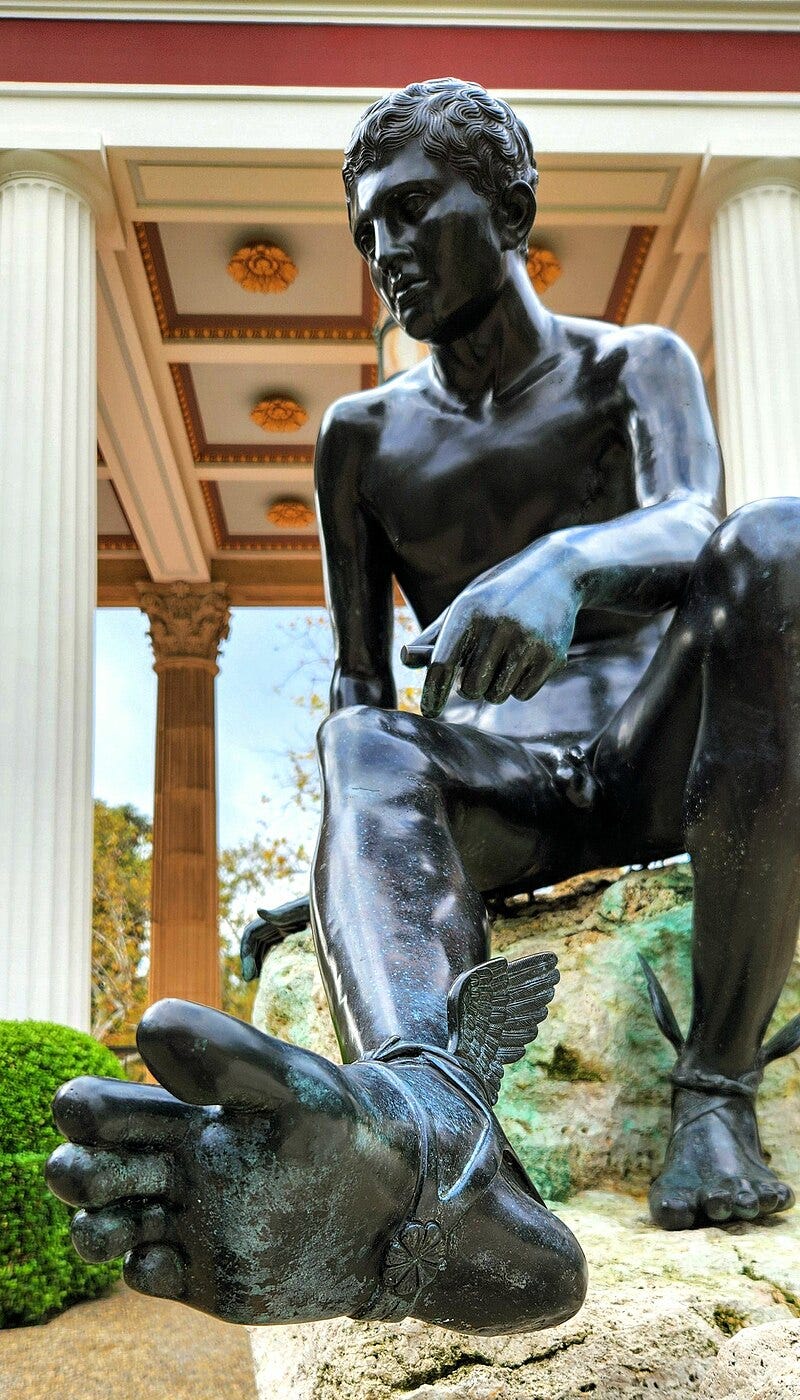

Hermes, the Greek god of boundaries, transitions, and communication, is one of the most dynamic and versatile figures in the ancient pantheon. From his origins as a trickster-child who stole Apollo’s cattle, to his mature role as the guide of souls and divine messenger, Hermes exemplifies movement—between places, realms, and even categories of being. While other Olympian gods were often fixed in their domains—Poseidon in the sea, Athena in war and wisdom—Hermes operated between worlds: heaven and earth, mortal and divine, life and death.

Hermes’ genealogy places him as the son of Zeus and the Pleiad Maia, a daughter of Atlas. Born in a cave on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia, Hermes’ infancy is marked by immediate action. On the very day of his birth, as told in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, the baby god invents the lyre by stretching strings over a tortoise shell, steals Apollo’s cattle, and covers his tracks with clever misdirection. This early myth signals Hermes' essential qualities: invention, wit, mischief, and cunning. He is not a god of brute force or domination, but one of intelligence, language, and mobility.

Hermes’ association with travel and communication made him particularly important in Greek society. He was the patron of travelers, merchants, heralds, athletes, and thieves. His image—often a youthful figure with winged sandals and a herald’s staff (caduceus)—appeared on waymarkers and crossroads, and his presence was invoked in both domestic rituals and public ceremonies. The hermae, stone pillars topped with the god’s head and male genitals, were placed at boundaries to invoke his protective power and to ensure safe passage.

Yet Hermes was more than a god of borders—he was a god of transformation. He guided souls to the underworld as psychopompos, linking him to death and the afterlife. He mediated disputes, delivered messages from Olympus to mortals, and served as a companion to both gods and heroes. In many ways, Hermes was the divine embodiment of liminality: he did not rule any one space, but instead presided over transition itself.

This makes Hermes particularly unique among the Olympians. His power came not from absolute command over a natural force, but from his fluency in change. His divine territory was not elemental, like that of Demeter or Hephaestus, but conceptual—he governed motion, words, and exchange.

Hermes in Ancient Literary Works

Hermes appears in numerous ancient texts, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Homeric Hymns, Hesiod’s Theogony, and later works by authors such as Euripides and Ovid. In each of these, his role reflects his multifaceted character and reinforces his function as a divine intermediary.

In Homer’s Iliad, Hermes takes on the critical role of protector and guide. In Book 24, when Priam bravely enters the Greek camp to ransom the body of Hector, it is Hermes who escorts him through the dangerous terrain, disguised as a mortal. This appearance highlights Hermes’ compassion and loyalty to duty; he is a god who not only moves between realms but facilitates reconciliation. The moment is poignant: Priam, a mortal father stricken with grief, is aided by the divine in his appeal for humanity amidst war.

In the Odyssey, Hermes is even more active. He serves as Zeus’s messenger, sent to command Calypso to release Odysseus from her island. Later, he delivers the magical herb moly to Odysseus to protect him from Circe’s enchantments. These appearances reinforce Hermes' role as both protector and liberator, a deity whose interventions help mortals navigate perilous transitions. Notably, he does not act as a deus ex machina but rather empowers mortals to act for themselves.

The Homeric Hymn to Hermes, one of the most delightful in the collection, provides an origin myth that is both humorous and profound. It showcases the infant god’s trickery and genius as he invents the lyre, steals cattle, and bargains his way into Olympus. The hymn ends with reconciliation between Hermes and Apollo, with Hermes gifting the lyre and becoming an honored member of the divine order. Here, Hermes embodies not only the power of speech and persuasion but also the potential of intellect to subvert and eventually support authority.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Hermes is mentioned in the genealogical catalog of gods but plays a less prominent narrative role. His identity as a child of Zeus aligns him with the ruling divine order, but unlike his siblings Athena or Apollo, Hermes is associated less with law and more with movement and improvisation.

Later authors, including Ovid in his Metamorphoses, would continue to feature Hermes (Mercury in Roman tradition) in stories that emphasized his role as a communicator and boundary-crosser. One of the most well-known is the tale of Hermes and the nymph Herse, in which the god's pursuit of love becomes entangled with trickery and divine jealousy. These stories expand on Hermes’ role not only as a god of commerce and diplomacy but also of sensuality and spontaneity.

In Greek tragedy, Hermes rarely takes center stage, but his presence is invoked in key moments. As psychopomp, he appears in funerary rites and invocations, emphasizing his role in the human experience of death and remembrance. The boundary between life and death, like all others, is one Hermes crosses with ease.

Hermes as a Deity and Modern Relevance

To understand Hermes as a deity is to explore a divine archetype that challenges conventional categories. He is a god of ambiguity, of motion and change, of cleverness over brute strength. In contrast to gods who demand worship through fear or awe, Hermes earns reverence through relevance. He is not always moral in the traditional sense—he lies, he steals—but he is indispensable. He makes systems work, keeps words flowing, enables travel, and ensures that the boundaries between worlds do not become impassable.

Hermes' role as a trickster links him to a global archetype found in many mythologies—Loki in Norse tradition, Anansi in West African tales, or Coyote in Native American lore. Tricksters are boundary-breakers. They challenge order, but they also create space for innovation. In the case of Hermes, his theft of Apollo’s cattle is not an act of destruction but of ingenuity. He leaves no trace, hides the evidence, and invents music along the way.

As such, Hermes stands as a symbol of creativity born of transgression. He reminds us that disruption can yield discovery, and that the rules of a system often rely on the existence of someone who can both bend and uphold them. This duality makes Hermes uniquely modern.

Relatable Traits of Hermes in Contemporary Life

In an age defined by communication technology, Hermes is more relevant than ever. He represents the infrastructure of information—the emails, texts, broadcasts, and signals that keep the modern world turning. Just as Hermes connected Olympus to the mortal world, today’s communicators—journalists, diplomats, translators—carry out similar functions, navigating between realms of thought, language, and culture.

Hermes is the patron of travelers, and in a globalized society marked by constant movement, he symbolizes the freedom and risk of crossing boundaries—physical, cultural, or ideological. He blesses the curious, the displaced, and the adaptable. In times of crisis, Hermes is with the migrant, the diplomat, and the explorer.

As a guide of souls, Hermes represents our relationship with death—not as a destroyer, but as a companion on the journey. In this way, he is echoed in the figures who help us face mortality: hospice workers, therapists, spiritual counselors. Hermes does not end life; he helps us understand the transition. His function provides a metaphor for the process of letting go, moving on, and making peace with change.

Hermes’ love of wit, invention, and cleverness makes him a symbol of the innovator. In every hacker who rewires a system, every artist who reimagines convention, every startup founder who finds a loophole in the market—Hermes is present. His brand of intelligence is agile, creative, and resilient. He reminds us that intelligence is not only about knowing but about doing—acting quickly and thinking flexibly.

Hermes is the patron of thieves and vagabonds—not because he condones crime, but because he recognizes the humanity of the outsider. In modern life, this aligns with the social advocate, the public defender, or the person who refuses to ignore those at society’s edges. Hermes reminds us that everyone travels, and that safety at the margins is as important as safety at the center.

Ethical Ambiguity and Human Empathy

One of the most fascinating aspects of Hermes is his ethical ambiguity. He is not an easy god to pin down. He lies to achieve goals, yet also mediates peace. He tricks, but he does not destroy. In this way, he mirrors the complexities of real human morality. Life is not always about choosing right or wrong, but about navigating competing values, managing transitions, and making meaning in ambiguity.

Hermes is also deeply empathetic. He helps mortals—Priam, Odysseus, Perseus—not because he must, but because he chooses to intervene. He honors negotiation over violence, persuasion over coercion. In our divided and polarized world, Hermes offers a divine model for diplomacy, empathy, and relational intelligence.

Hermes, the messenger god of ancient Greece, has never truly left the stage. His presence persists in our technologies, our travels, our transitions, and our trickery. As a figure who moves between worlds, he embodies the human condition: always in flux, always searching, always speaking. In literature, he is a conduit of both comedy and grace, and in life, he is a metaphor for change managed with wit and heart.

Unlike Zeus, who rules with thunder, or Ares, who charges into war, Hermes teaches us how to move—between roles, between beliefs, between lives. He is the god of the journey, and in honoring him, we honor the journey itself.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

How does Homer portray the tension between personal honor and communal responsibility in Hector’s decision to fight Achilles?

Does Achilles' treatment of Hector’s body diminish his status as a hero? Why or why not?

What is the role of divine intervention in Book 22, and how does it affect our understanding of free will and fate in the poem?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 23. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled Funeral Games for Patroclus and covers pages 559-587. In the Wilson translation, it is called Funeral Games and covers pages 545-579.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid subscriber is the single most impactful way you can support the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature here at Beyond the Bookshelf. An annual subscription is only $12/year.

If you can’t commit to a paid subscription at this time but would still like to support my work, please visit my support page for a list of other ways you can help keep the lights on.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

Achilles is certainly no hero, and the other soldiers stabbing Hectors dead body are no better. Even today it seems harder to be a gracious winner than a gracious loser, with everyone trying to “own” the “other side”.

And I always thought Hermes was the god of $10,000 handbags… who knew?

Again, I love to read Matthew’s musings after reading the chapter myself, especially his exposition on Hermes. But I don’t agree with his statement that Homer ‘critiques the heroic ideal’. I believe that is a too modern interpretation. ‘Homer’ – or whoever crafted or transmitted the story – was drenched in the same culture of the ‘classic heroic ideal’ as anybody else in those times. It is tempting to interpret the descriptions of extreme violence and resulting grief as moral condemnations of war, but in Homer’s time and (much) later it was just the description of - or meditation on - the general human condition, although with some hyperbole added for dramatic impact. That is why these stories can be fascinating but also offputting for a modern audience: the trenchant misogyny especially, but also the almost total disregard of animal and human lives in much of the epic reflect a culture very distant from our own in heroic ideals and moral convictions, but still echoing our inherent nature as, at least partly, unreasoned and cruel or plain stupid creatures making live on this earth more miserable than it could be for everyone involved because of our eternal limitations as moral human beings.