Exploring Life and Literature.

*Regular newsletters appear on Tuesdays. The Deep Reads Book Club newsletters appear on Fridays. You can find all the book club details at the link below.*

“Now, balanced against each other, he placed two fatal fates of death, one for the horse-taming Trojans, one for the bronze-armored Achaeans. Gripping the beam, he raised it by the middle … Down went Achaea’s day of doom, Achaea’s fate settling down on the earth that feeds us all, as the fate of Troy went lifting towards the sky.”

Dear friends,

Book 8 of The Iliad, marks a pivotal shift in the Trojan War as Zeus asserts his authority and alters the course of the conflict. From the beginning, Zeus makes his will clear: no god may interfere in the battle, cementing his absolute power. He emphasizes this decree with a dramatic display of thunderbolts, striking terror into the hearts of the Achaeans and forcing them into retreat. This divine intervention grants the Trojans a significant advantage, allowing them to push forward under the relentless leadership of Hector. As night falls, the Trojans camp confidently outside the Achaean fortifications, a powerful symbol of their growing dominance. Emboldened by their success, Hector delivers a confident speech, foretelling Troy’s imminent victory and the Achaeans’ impending downfall.

These events are deeply rooted in the tension between mortal effort and divine intervention. While the Achaeans fight with courage and skill, their fate ultimately lies in Zeus' hands. Athena and Hera, devoted patrons of the Achaeans, wish to aid them, but Zeus forbids it. His decree is final, reminding mortals and immortals that his will cannot be contested. This moment underscores one of The Iliad's most enduring themes: the interplay of power, fate, and resilience in the face of adversity.

Despite the Achaeans’ suffering, they refuse to surrender entirely. Agamemnon, their leader, calls upon his troops to rally and prays for divine relief. Zeus grants him a sign—an eagle carrying a fawn—rekindling the Greeks’ fighting spirit. The skilled archer Teucer takes advantage of the moment, felling many Trojan warriors. However, Hector, seemingly unstoppable, wounds Teucer, reversing the tide again. Hector seizes the opportunity to press forward as the Achaeans retreat behind their fortifications. He orders the Trojans to camp outside the Achaean wall, ensuring that the enemy cannot escape under cover of darkness. His confidence is unwavering—he is certain that victory is at hand.

The shift in momentum from the Achaeans to the Trojans mirrors the broader themes of power dynamics and fate. Zeus' intervention demonstrates how external forces, whether divine or circumstantial, can dramatically alter the course of events. This concept remains relevant today, as leaders and individuals must navigate unforeseen challenges and shifting tides in politics, business, and personal endeavors. Just as the Trojans capitalize on their sudden advantage, success in life often depends on recognizing and seizing opportunities when they arise.

Hector embodies the determination of an individual striving for greatness and the influence of forces beyond his control. His battlefield prowess and leadership inspire his men, but Zeus’ favor undeniably shapes his triumphs. This raises a thought-provoking question: how much of success is determined by personal effort, and how much is dictated by external factors? This tension between free will and destiny is as relevant today as it was in Homer’s time.

The Achaeans demonstrate resilience despite their setbacks. Their retreat is not a complete defeat but rather a strategic necessity. In this way, The Iliad offers a lesson in perseverance: setbacks, while discouraging, are rarely final. Instead, they serve as opportunities to regroup, strategize, and prepare for future battles—whether on the battlefield, in careers, or in personal struggles.

As Book 8 draws to a close, the scene is set for the next phase of the epic. Zeus informs the gods that only Achilles can prevent the Achaeans’ destruction, foreshadowing the legendary warrior’s return to battle. Meanwhile, the Trojans remain outside the Achaean walls, their campfires burning brightly against the night sky. This final image is both ominous and poetic, reflecting the precarious balance of fate and foreshadowing the battles to come.

In The Iliad, war is more than a series of battles—it is a meditation on human nature, leadership, and destiny. Book 8 serves as a crucial turning point, reinforcing the themes of divine influence, shifting fortunes, and the endurance of the human spirit. Though set in the realm of myth, these themes continue to resonate, reminding us that, while fate may set certain conditions, resilience, wisdom, and adaptability shape our ultimate outcomes.

“Whoever bends to break my will, I hurl him down to the shadowy depths of Tartarus, far, far below the deepest pit of earth … then he will see just how much stronger I am than all the rest of you gods.”

Greek mythology is built upon a foundation of divine power, heroic struggle, and the intricate balance between fate and free will. At the heart of this vast mythological landscape stands Zeus, the supreme ruler of Mount Olympus. His role in The Iliad is particularly compelling, as he embodies the paradox of ultimate authority constrained by forces beyond his control. While Zeus dictates the ebb and flow of battle, his will is not absolute—he must navigate a complex web of obligations, balancing the demands of fate, the pleas of his fellow gods, and his own personal inclinations. In The Iliad, Zeus emerges not only as a ruler of gods and men but also as a figure bound by the very cosmic order he seeks to enforce. His internal conflicts and decisions highlight the tension between power and limitation, revealing a god who is both an enforcer of fate and a participant in its unfolding drama.

From the outset of The Iliad, Zeus asserts his dominance over mortals and immortals. He holds the scales of fate, determining the outcomes of battles and the destinies of warriors. In Book 8, he explicitly forbids the gods from intervening in the Trojan War, demonstrating his desire to enforce order and prevent divine interference from disrupting the natural course of fate. His thunderbolts serve as both a warning and a symbol of his unmatched power, forcing even the most defiant gods into submission.

Yet, Zeus’ authority is not as absolute as it appears. He is often depicted as a mediator rather than an unchallenged ruler. He must placate Hera, whose wrath and jealousy over his affairs frequently lead to divine discord. He negotiates with Thetis, promising to honor her request to aid Achilles, despite knowing that such interference will shift the war’s balance. His role, therefore, is not simply that of a tyrant imposing his will but of a ruler navigating the turbulent waters of divine politics, personal debts, and inescapable destiny.

Despite his position as king of the gods, Zeus is not omnipotent. His greatest limitation comes from the concept of fate (moira), which exists as a force even he cannot override. While he has the power to influence events, he is ultimately bound by the predetermined course of destiny. A striking example of this occurs when he contemplates saving his son, Sarpedon, from death. Zeus expresses a rare moment of vulnerability, debating whether to defy fate and spare Sarpedon from his doomed encounter with Patroclus. However, Hera reminds him that if he intervenes, the natural order will unravel, forcing him to relent and allow his son to die in accordance with fate’s decree. This moment underscores the paradox of Zeus’ power—he can shift the tides of battle, but he cannot overturn the fundamental laws of the universe.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Zeus’ character in The Iliad is his tendency toward favoritism, which complicates his role as an impartial enforcer of fate. While he claims to uphold balance, he frequently acts in ways that suggest personal investment in the war’s outcome. His favoritism toward the Trojans, particularly Hector, leads him to shift the battle in their favor despite knowing that Troy is ultimately fated to fall. His manipulation of events reflects his personal desires and attachments, demonstrating that even the king of the gods is not immune to bias.

This favoritism breeds resentment among the other gods, leading to moments of defiance and rebellion. Hera and Athena, both staunch supporters of the Greeks, act against Zeus’ decree, intervening in battle when they see fit. This rebellion illustrates the limitations of Zeus’ rule—not only does fate constrain him, but he also struggles to maintain control over his own divine council. Despite his efforts to impose order, chaos remains an inherent part of the cosmos, reinforcing the idea that even the supreme deity is subject to forces beyond his absolute command.

Zeus’ role in The Iliad serves as a meditation on the nature of power—its reach, its limitations, and the burdens it imposes. Though he is the most powerful entity in Greek mythology, he is not free from obligation, resistance, or cosmic law. His decisions shape the course of the Trojan War, yet he remains bound by the dictates of fate and the will of the gods around him. His struggles reflect the eternal tension between authority and limitation, highlighting the complexities of leadership, justice, and divine intervention.

In the grand scheme of The Iliad, Zeus embodies the paradox of power: a ruler who must enforce destiny while grappling with the constraints that destiny places upon him. His story is not one of unchallenged dominance but of a god navigating the intricate balance between control and inevitability, making him one of the most compelling figures in Homeric tradition.

Here are a few questions to think about. Feel free to discuss these or any others that may be of interest.

How does Zeus' involvement impact the battle’s progression? What does this tell us about the relationship between gods and mortals in The Iliad?

Zeus sends an omen to the Achaeans in the form of an eagle and a fawn. How do the Achaeans and Trojans interpret signs from the gods differently?

Hector taunts the Achaeans and gains confidence. How does his character evolve in this chapter, and how does Homer portray him compared to earlier depictions?

Nightfall brings a pause to the battle. How does this enforced break in fighting contribute to the tension of the narrative?

Reading Assignment for Next Week

We will cover Book 9. In the Fagles translation, this chapter is entitled The Embassy to Achilles and covers pages 251-275. In the Wilson translation, it is called The Embassy and covers pages 197-222.

Beyond the Bookshelf is a reader-supported publication. If you are looking for ways to support Beyond the Bookshelf, please visit my support page and see the ways you can help continue the mission of exploring the connection between life and literature.

Until next time,

Previous articles in this series:

If you are a new subscriber or missed any of the previous articles in this series, you can catch up at the link below:

All opinions in this essay are my own unless otherwise noted. Additionally, I have highlighted all sources in the text if needed.

In Mediterranean and Persian iconography, human power was symbolized by the Bull. And divine power was embodied in the Lion (this could also be called the power of Nature). Hector is the bull in this scene, pawing the ground, sensing victory. Both Zeus and Achilles are Lions, divine, yes, and as dangerous at rest as on the hunt.

Once again, your essay provides needed (at least for me) clarity and deeper understanding. My initial takeaway from Zeus warning other gods to stand down and then Zeus himself intervening was just a an example of Zeus's duplicity.

Until reading your essay, my focus seems to have been too much on the whimsy and perfidy of the gods, overlooking the uncontrollable role of fate. It seems when you mix all of these forces together, man can conjure up an explanation or justification for whatever happens, pretty much eliminating any element of free will. Interestingly, the debate about the role of free will v. what is hardwired in our brains continues robustly in modern times.

The prominence and power of Hector in Book 8 shows how strong a mortal could become with Zeus in his corner. Hector becomes dominant in all respects and virtually immune from harm.

One detail confused me a bit. When Athena is gearing up to intervene, she complains about Zeus favoring the Trojans, but at the same time mentions that Zeus is fulfilling the plans of Thetis who begged Zeus to exalt Achilles (Fagles, lines 423-425). I don't see how favoring the Trojans is exalting Achilles. If Athena believes Achilles will ultimately be exalted, why does she feel compelled to intervene? My confusion may just be a lack of understanding.

My favorite line in all of Book 8 is the very first. What a lovely description of dawn.

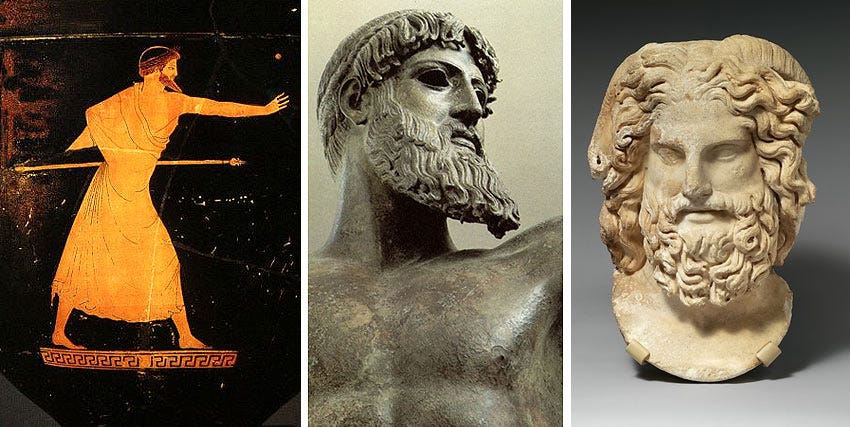

Once again, the art accompanying the essay is great -- and I love the comments from Bump on a Log, as well as Bump on a Log's name. Wish I had thought of that!